That the university should formally recognise and build on the example of these leaders in anti-apartheid activism and education seems like a reasonable proposal, and perhaps even a belated one, given the extent of the impact these figures had on progressive thinking and action against apartheid internationally. Instead, reservations about the campaign seem to revolve either around the classification of Israel as an apartheid state, or else, accepting this classification, around the issue of formally introducing an apartheid-free campus proviso into Trinity’s research and development policies. This latter measure, some individuals have suggested, would be to the detriment of more general values of open academic exchange and freedom which Trinity extends to all potential partner institutions – in other words, regardless of these institutions’ records of collaboration with apartheid states, crimes, or policies. Although both of these concerns are in fact anticipated and responded to on the campaign’s website, this article attempts to deal with such reservations and to represent the Campaign’s goals and provisions as fairly as possible.

Findings

Firstly, the campaign does not associate Israel with apartheid flippantly, or even for the sake of provoking discussion on this point. Rather, the campaign takes the conclusions of the International Russell Tribunal on Palestine as providing adequate consensus for the usage of the term ‘apartheid’ in relation to the organisation and policies of the Israeli state. The executive summary of the Tribunal’s sessions in Cape Town, November, 2011, reads as follows:

[The] Tribunal concludes that Israel’s rule over the Palestinian people, wherever they reside, collectively amounts to a single integrated regime of apartheid… The state of Israel is legally obliged to respect the prohibition of apartheid contained in international law. In addition to being considered a crime against humanity, the practice of apartheid is universally prohibited.

These findings have been reiterated in the Tribunal’s sessions since 2011, and it is in light of such statements that the terminology of the Apartheid-Free Campus petition has been decided. The petition urges the provost and board of the university to support apartheid-free standards of education and research by bringing the following measures into effect:

– an end to research affiliations with firms that operate in or provide security services for Israel’s occupation zones in Palestine;

– a severance of ties with Israeli institutions which have not condemned Israel’s illegal policy of occupation and settlement in Palestine, and which do not offer equal educational rights and access to Palestinian academics;

– a policy of non-participation in co-funded or shared research projects with such universities, institutions and firms, while Israel’s programme of occupation and discrimination against the Palestinian people persists.

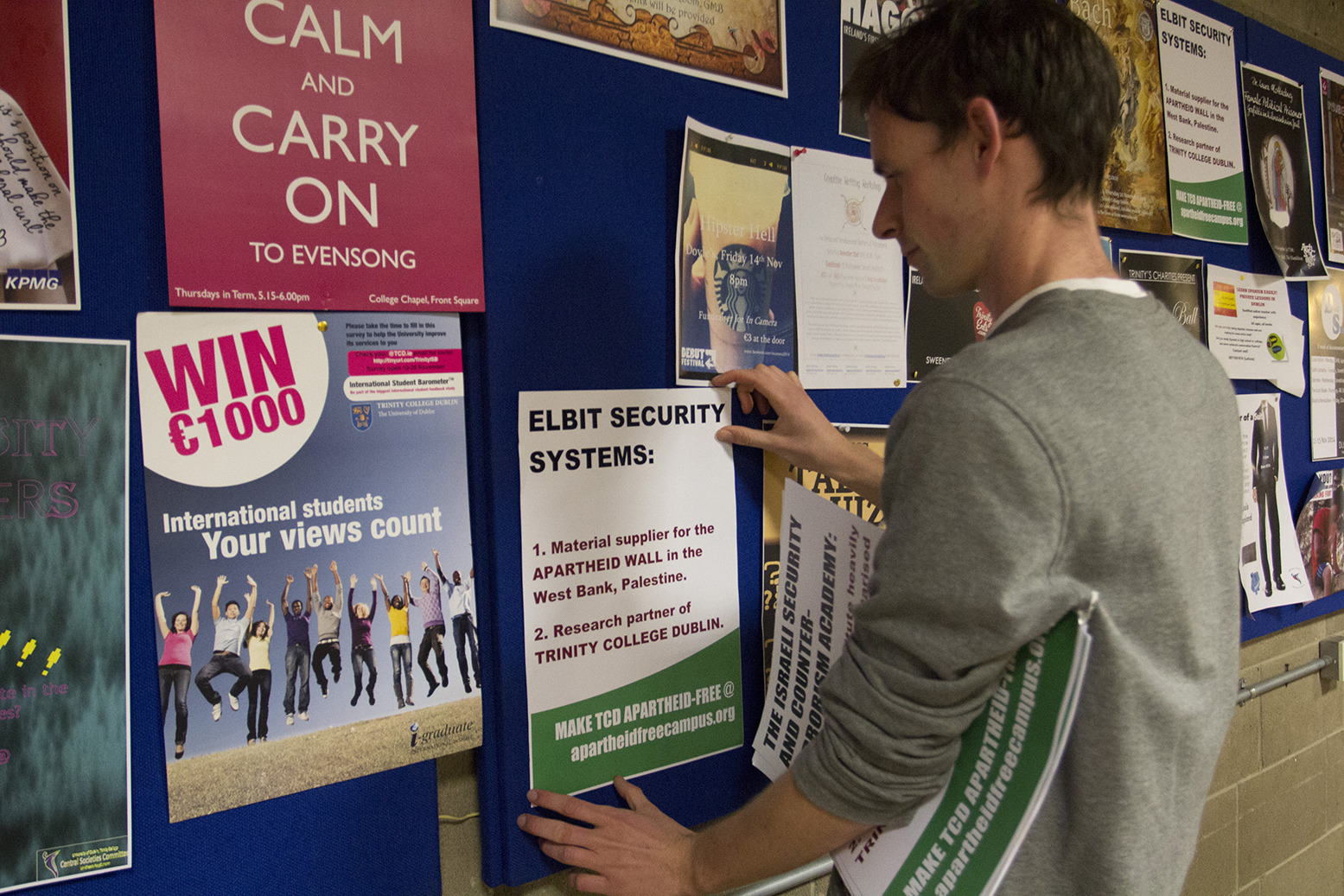

What this would amount to on a practical level would be a refusal to collaborate further with Trinity’s recent (and current) research partners in Israel. First: the private security firm and drone manufacturer Elbit Systems, which is one of the key suppliers of building and surveillance materials for the illegal apartheid wall in the West Bank, Palestine. As Trinity News reported in February 2014, academics from Trinity collaborated on an airport security project with this firm, and they are still engaged in ongoing security research programmes, scheduled for completion in 2015. Another of Trinity’s research partners that would be affected by the Apartheid-Free Campus proviso is the Israeli Security and Counter-Terrorism Academy, an institution infamous for its development and training links with illegal security programmes in the Occupied Territories, Palestine. Lastly, there is the Weizmann Institute of Science, a long-term research partner of Trinity, which also has a continuing record of service provision for the Israeli military establishment. Future academic links with these (and similar) institutions, particularly under the Horizon2020 research network programme, would also be forgone.

Different kind of boycott

Importantly, however, and although there may be some persuasive arguments in favour of such a stance, the TCD petition does not call for a total boycott of Israel per se. Indeed, this distinguishes the TCD Campaign from movements demanding the full intellectual and cultural boycott of apartheid states, which Kader Asmal in Trinity, and other members of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement, helped to realise in the case of apartheid South Africa. The terms of the TCD petition are precise in advocating for a condemnation of apartheid crimes and an official refusal to collaborate with institutions that support their continuance, in this case in Israel. One result of this is that, hypothetically speaking, should academics in TCD wish to co-ordinate research with programmes run by an institution like B’Tselem (The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories), or the Alternative Information Center, then such academic ventures would not be impeded by the college-wide Apartheid-Free Campus proviso.

In contrast to the Israeli establishments with which TCD has traditionally collaborated, B’Tselem and the AIC have formally condemned Israeli policies of occupation and settlement (among others); they do not contribute funding or research to the furtherance of such projects on legal and humanitarian grounds; and they maintain a non-discriminatory employment access policy in their own workplace and research. So the petition takes into account the respect for human rights and humanitarian standards which certain Israeli institutions promote and adhere by, and this is directly reflected in the academic measures it calls for. However, and perhaps more importantly, the campaign also highlights the fact that no discussion of academic freedom and accountability with regard to the policies of the Israeli State can proceed in good faith without recognising the rights of Palestinian academics, their families, and other members of the civilian population. According to the United Nations, Israel’s unlawful assault on Gaza from July-August 2014 alone resulted in the death of an estimated 1,462 civilians, including 495 children, as well as the damage of 228 schools, 26 to the point of total destruction.

This is in addition to Israel’s continuing policies of occupation, settlement, and discrimination against the Palestinian people. In fact, it was in addressing these broader, ongoing crimes in 2004 that the International Court of Justice ruled that all states have a legal obligation to take steps that will end Israeli violations of international law, particularly as they relate to the separation wall and the construction of settlements on occupied Palestinian territory. This was also the year that the Palestinian Federation of Unions of University Professors and Employees first called on the international academic community to review, and if necessary to suspend, research links with Israeli institutions until the educational and human rights of the Palestinian people are respected by Israel. In spite of the fact that this appeal has been reiterated on numerous occasions since 2004, Trinity has retained and increased its research affiliations with Israeli institutions in recent years. It is on this point, perhaps, that the second concern about ‘academic freedom’ in Trinity’s research policies comes most plainly into view. For the fact is that the supposedly neutral position of academic inaction is severely undermined in Trinity’s case.

This is a stance that would maintain current research links with Israeli institutions which support apartheid practices, and do nothing to avoid further links of this kind from developing in the future. Trinity’s research and development record has consistently neglected Palestinian academics’ demands for peaceful solidarity against the criminal practices of the Israeli State. Furthermore, such neglect has been accompanied by an active increase in coordination with establishments that have unambiguous links to Israel’s illegal and discriminatory policies against the Palestinian people. Formal inaction on Trinity’s part will only compound the university’s record of biased neutrality to date, and give further academic ratification to the ongoing crime against humanity that is Israeli apartheid.

If Trinity is to be an institution of international standing and pioneering example, as we’re told it should be, then it can start by upholding ethical, apartheid-free standards of education in the research affiliations it pursues.

College reputation

Trinity’s recently launched strategic plan clearly states that the university’s research policies and affiliations are integral to the image and standing of the university, particularly in a global context. The TCD website states that “Trinity has an open approach to creating value from research…in partnership with enterprise and social partners”, and moreover that “its research continues to address issues of global, societal and economic importance.” Once seen in light of Trinity’s affiliations with Israeli institutions, however, such assertions take on a disturbing aspect. Generating value from research, after all, shouldn’t come at the price of creating a culture of impunity for violations of international law, and certainly not in the name of some non-existent right of universities to ignore the systems of political injustice which they simultaneously profit from. The institutional links we cultivate are directly related to the broader academic and state policies we endorse. Academic complicity in apartheid crimes cannot be justified by heedless emphasis on global innovation, nor vindicated by highly preferential notions of academic freedom.

This is particularly the case when such notions, as they are actually reflected in a university’s research policies, tacitly reject the rights of employees and students in Palestinian universities, in favour of lucrative funding contracts with institutions in Israel that support state measures defined principally by their appalling violence and blatant illegality. If Trinity is to be an institution of international standing and pioneering example, as we’re told it should be, then it can start by upholding ethical, apartheid-free standards of education in the research affiliations it pursues. The Apartheid-Free Campus petition is one among a number of affirmative, progressive steps which members of the TCD community can take to see that happen.

Photo: Matthew Mulligan