I’m an artist of sorts who was diagnosed with clinical depression six years ago, and there hasn’t been much brooding inspiration involved. Largely, it’s been an inglorious hamster-wheel where I stay in a tiny space and run myself into circles so quickly that it looks like I’m standing still.

There do exist many examples of artists who have depression. That is because there exist many examples of people who have depression – at least one out of every ten adults in Ireland, and they’re just the ones we’ve managed to diagnose.

Perhaps there are features of art and writing that might attract disproportionate numbers of us to those fields: perhaps the value placed on introspection, the fact that you don’t need to be consistently happy and functioning, the fact that the social demands placed on you are comparatively low, might draw us in.

On the other hand, there are many aspects that could be seen as peculiarly off-putting to people who have my illness. Having to retain a sense of faith and purpose in yourself and the thing you’re doing; the lack of direction and the need to keep shouldering on in rejection; the isolation; the biting comments from strangers; the expectation to share your story when, in your daily life, you can barely look your friends in the eye or answer questions about how you’re doing with any degree of candour.

Even the factors that make an artistic career attractive to people handling their depression poorly – not having to talk to people, not having to get out of bed by a certain time every day – could easily render it anathema to people coping well or aspiring to cope well. Several healthcare professionals have urged me to do things that ‘get me out of the house’, even if I see no other purpose in them. People with that aim would be better off in an office job.

Think of the stereotypical languishing-martyr-to-own-brilliance. They’re usually drinking too much, aren’t they? And working all night and agonising over tiny details. If they did that minus the ‘artist’ title, it would be recognised as self-destructive behaviour that no-one could comfortably glamourise except at an absolute distance from the condition a depressed person lives with.

My imbalanced brain chemistry, alas, cannot be put in a tupperware lunchbox until I feel like coming back to it.

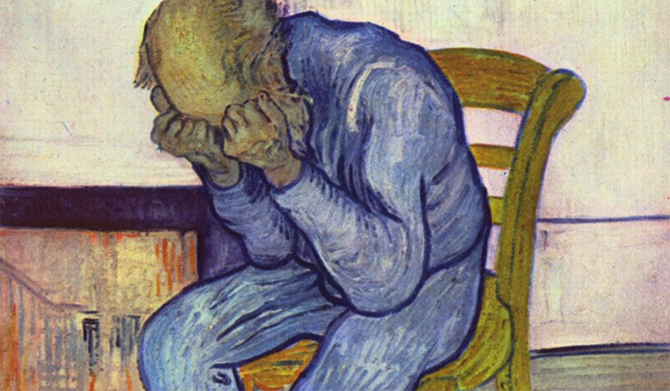

Speaking for myself – and when it comes to mental illness, yourself is the only person you should ever claim to speak for – my depression flattens my creativity.

It doesn’t necessarily heighten my feelings or even, in a looser sense, my perception. Often, I end up inured to every last internal or external factor of my existence besides the sensation of someone driving a thousand tiny nails into me. It’s outside vocabulary, outside verbalisation. I tell people that I have a headache, or that I’m tired – and though I know full well I’m lying through my teeth, it’s because I don’t know what the true thing to say would be.

Nor can I compress my experience and articulate it better when I’m feeling well again. I can only comprehend it while it’s happening. My imbalanced brain chemistry, alas, cannot be put in a tupperware lunchbox until I feel like coming back to it.

Having an illness, in short, does not help me to create things. The inanity of even having to articulate this is striking – are diabetic poets ever put in the position of clarifying that they, and not their diabetes, write their poetry? But as Seán Healy wrote in University Times, there is an ongoing perception that my illness, though it functionally debilitates me, doesn’t ‘count’ as a medical issue.

Perhaps any vaguely positive representation of depression is better than writing off the people who live with it. But as a rehabilitative trope, the ‘depressed artist’ is also beyond elitist. If you don’t get published, you’re not a tortured genius: you’re a depressed person with no job. Cleaning bathrooms for minimum wage isn’t an instantiation of noble melancholy, because somewhere between Shelley and Byron, we decided that the artist-figure should have unique agency and selfhood under capitalism. Only a tiny subset of the labour market are able to ‘copyright’ their work or have it understood as ‘theirs’ notwithstanding the fact that someone paid them to do it. Funny that they should be the ones we care about valorising.

Celebrating artistic talent is good. Crediting depressed people with the ability to live productive lives is good. But our cultural conception of the depressed artist as a non-consenting participant in a Faustian bargain, their skills purchased at the cost of their mental health, is helping no-one.