With zero pretense, James Hussey identifies The Sickness Unto Death by nineteenth-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard as his favourite book, stating, “I probably reread it once a year.”

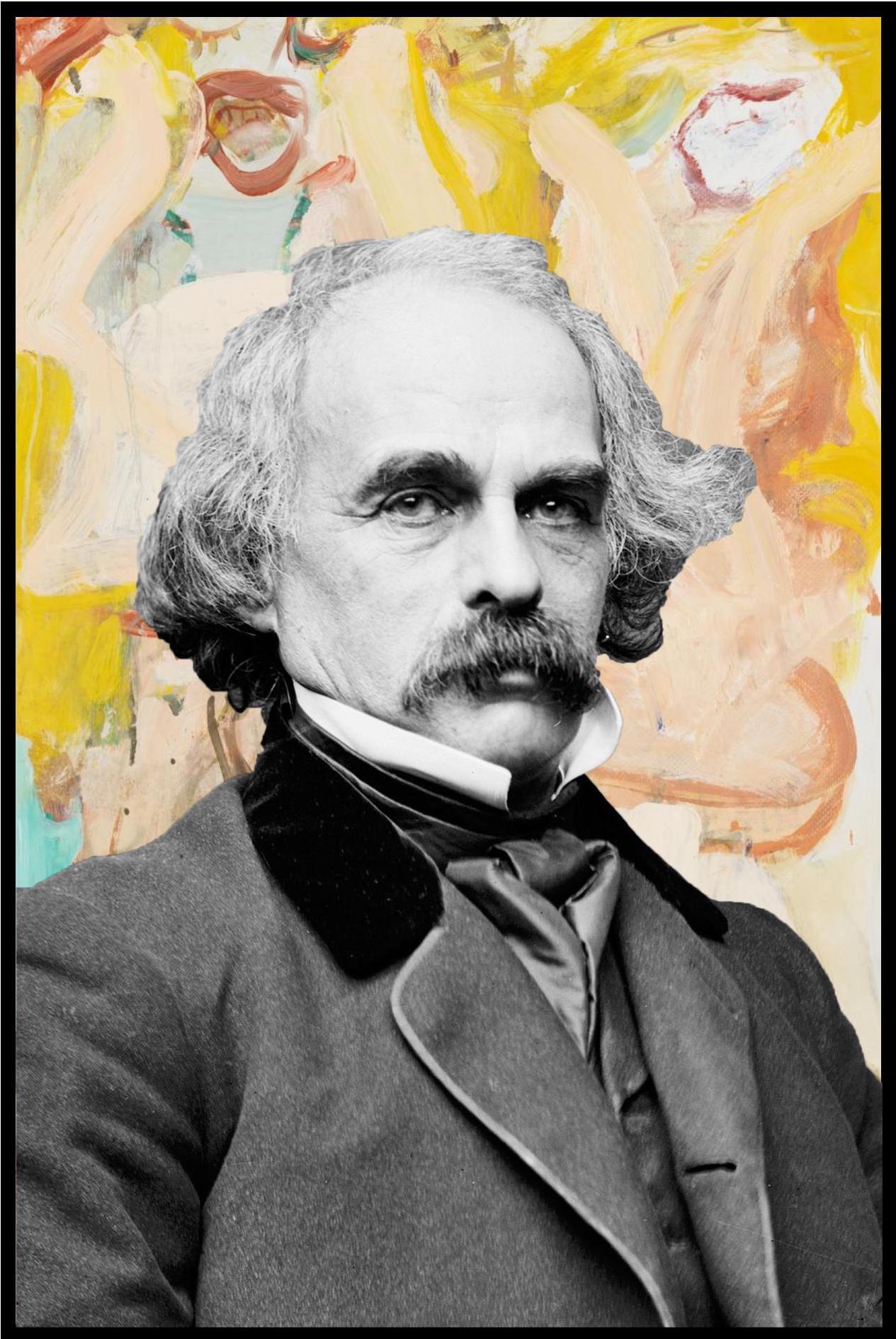

As a final-year Ph.D. candidate in the School of English, Hussey has never been a student of philosophy. Over the course of our conversation, however, it became clear that for him interdisciplinarity is extremely important to a university education, an attitude he feels is increasingly prevalent within academia, as well as reflective of his own work. Reading Kierkegaard has informed Hussey’s doctoral research into individualism in the writing of Nathaniel Hawthorne, just as studying paintings by the Group of Seven allows English students to further their understanding of postcolonial themes in literature.

This balance between work and interest, as present in his academic studies, is also reflected in Hussey’s attitude toward being a teaching assistant (TA) and a researcher. Although the workload for both positions is substantial, when asked whether he found it difficult to pursue his doctorate and be a TA at the same time, the question was met with an emphatic “No—I love it.” Elaborating further, Hussey stated, “I think it should be compulsory.”

Arguing for the importance of complimenting personal research with teaching, Hussey stressed how much he learns through being a TA, by listening to his students engage in discussion with each other and by being the architect of such conversations. Although Hussey acknowledges the many benefits of teaching in conjunction with research, he also makes sure to emphasise the fact for him, personally, it is imperative he have a life outside of his studies: “I have to stop at 6:00 pm. I don’t work weekends. I never have, and I don’t think I will.”

As societal conversations continue to emerge on the physical and mental health consequences of academic overwork and burnout and the gig economy, acknowledgments such as these are crucial for young people to hear. As a Ph.D. candidate, Hussey is open about the fact that he has had colleagues who have “made themselves ill” through overwork, and that there still remains “a massive unspoken element” with regard to the pressures of undertaking a doctoral degree.

Hussey’s honesty on the realities of pursuing a Ph.D. also carries over into his view of the current state of academia. Citing issues surrounding short-term contract work, high turnover rates, and the near certainty that he will have to go abroad to find work after he completes his Ph.D., Hussey is cognisant of what it means to be a twenty-first-century academic. Despite these issues, however, he remains “quite positive” and is prepared to face these problems in order to realise his teaching career.

Hussey also feels strongly about maintaining a balance between his social and academic lives. For him, leading a life outside the university allows him to take necessary steps back from his work and “get out” of his head, something he encourages all Ph.D. candidates to do. Whether watching “12 to 20 hours a week of sport” or cooking, allowing himself scheduled distance from his work ensures his personal interests do not become secondary to his academic pursuits.

Keeping in touch with his hobbies outside of academia also allows for a level of engagement with cultures outside of his own. In response to his interest in cooking, when asked if he watches the Netflix documentary series Chef’s Table, Hussey replied in the affirmative, citing an interest in the ways in which the new season chronicles Vladimir Mukhin’s reinvention of traditional Russian cuisine at the White Rabbit restaurant in Moscow.

Although he does not claim to be a model Ph.D. student, there is much to be admired about Hussey’s attitude towards academic life, namely that he has found personal success in keeping a balance between all aspects of himself, embodying Kierkegaard’s dictum to “be that self which one truly is.” Kierkegaard reminds us that to be an academic is not to be a one-dimensional body of studiousness, but a three-dimensional self with the many lives and interests we possess.