The President is the highest office in Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU), and although some may consider the Ents Officer as having the most significant effect on their student lives, the President is the most influential student leader on campus. The President has climbed to the top of the Trinity political world, usually on the back of a history of commitment and leadership within multiple societies and has a wide array of experience with SU affiliated positions. But most importantly, they will have won the support of the people through successfully selling their vision of how to run the Union in the hope of ensuring the best possible college experience for Trinity students.

During the campaign period, the aspiring Presidents try to authentically pledge commitment to innovatively improve and maintain high standards in daily college life. The aim of their campaigns is to convince you to believe that they, and they alone, are the only one that is capable of providing what you need as a student. However, as the SU elections are in motion, we look back to 1982, when the aim of some of the Presidential candidates was not merely to win at the ballot.

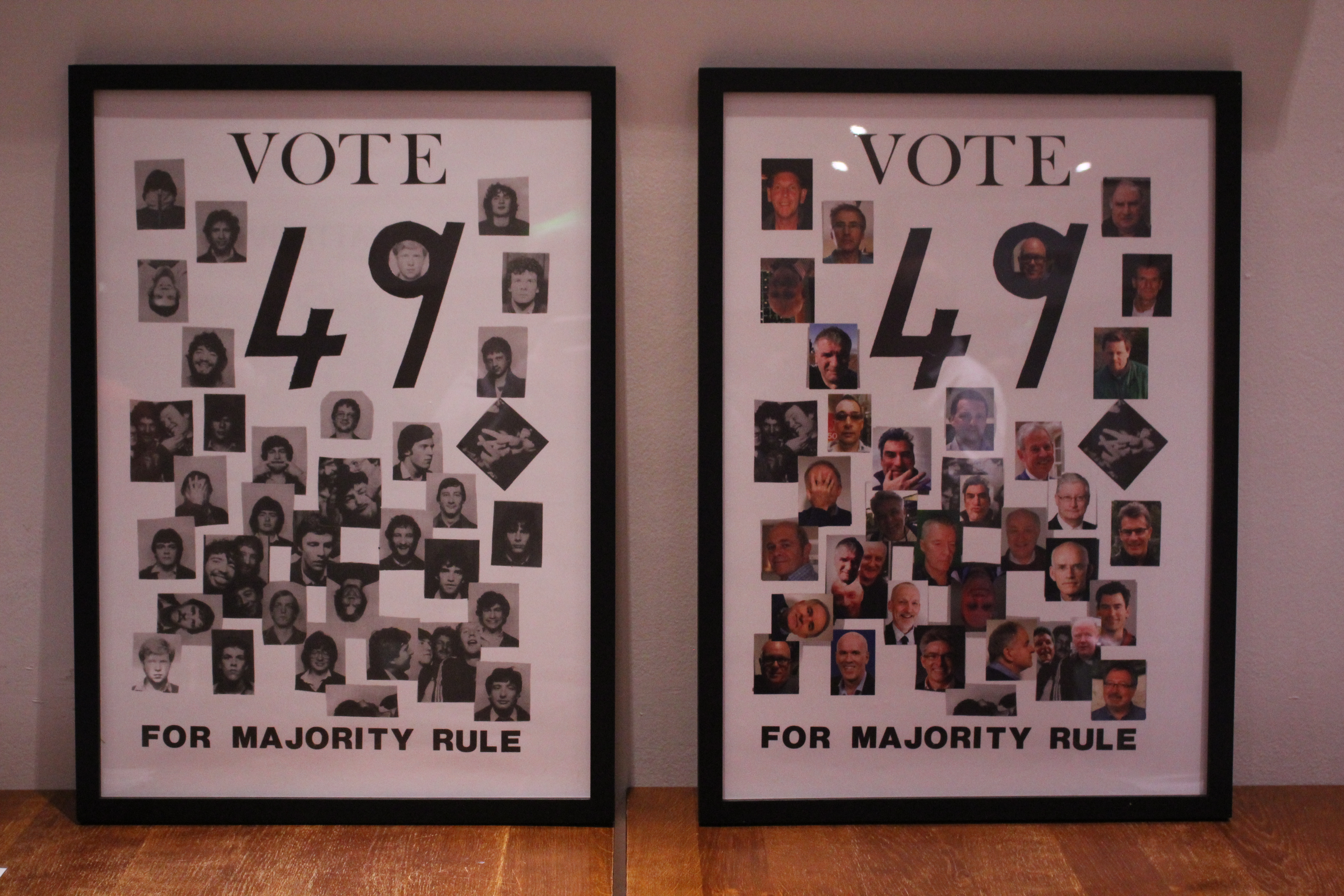

On December 2018, the Engineering class of 1979 to 1983 had their 35th anniversary reunion in the Pavilion Bar. The side room was bustling with former graduates and brimming with nostalgia for college days past. Centre stage sat a framed poster, retrieved from the depths of the 80s archives – the “forty-niners” Presidential campaign poster. Around the bold-printed rallying cry to “Vote 49” are portraits of a group of third year engineering students which were probably merely plastered on the page at the time, but now appears to be scattered in a retro, artsy-chic style. These were the students who had all just decided to run for President of TCDSU.

“It was a student prank”, explained Seamus Mockler, who now works with consultancy construction projects. “It was a slight bit of rebellion against the way things were”. Seamus Mockler was the auditor of the Engineering Society at the time, one of the main instigators of the campaign, and along with a dozen others that night, an ex-SU Presidential candidate.

The Pav was the very spot that the idea to gather as many of them as possible to run for the highest office of the student body had occurred to one of the disgruntled engineers of the class of 1983. “We were frustrated,” Mockler explains. “It wasn’t so much the left wing policies, it was the fact that we always seemed to be going out on the march for every cause on the planet except for our own.” All the graduates at the reunion could agree that the underlying motivation of the forty-niners was to poke fun at the SU, to “keep up the self-important guys who walked around with keys attached to their pockets for days counting the votes”, jokes David D’Arcy, now a freelance technical writer. However, the present forty-niners also consent to the fact that, in their joke, lay a message and a bold call for change.

The Eighties were famously one of the most potent times for student activism. The forty nine began their Trinity career at the time of Joe Duffy’s turbulent Presidential reign, notorious for the radical activism he fostered around campus. The engineer’s introduction to College life was the catering boycott, remembers Damien Owens, a chartered engineer. After someone had found a cockroach in a Buttery dish, the SU decided to boycott all the catering services around campus. For the whole academic year, from the spring of 1979 to the summer of 1980, a variation of rice and pasta sauce was offered by the SU in the Common Room.

In an edition of Trinity News from 1982, the front page tells of four different protests and “civil disobedience” happening around campus. It reports of students marching to the Dáil to protest the most recent cutbacks in the education sector, a student sitting in the Lecky protesting the lack of library services. Players were speaking out against the Dublin Grand Opera Society over the cross-over between their Hansel and Gretel panto productions, and the Women’s Group were protesting outside the GMB after the Phil had showed a screening of a pornography movie. Trinity campus was rife with dissent.

D’Arcy reiterates that “the real protests” were movements such as the AIDS awareness and anti-nuclear warhead protests. However, whether it was just merely a student prank, the engineering class were still wrapped up in it all, the “rite of passage” of participating in some student activism which historically seems to represent an inherent part of student culture.

As one may expect, no one in the forty nine engineers was present in the Pav as a former President of TCDSU. Neither did they stage a coup when Aine Lawlor came out on top. In fact, they all were glad when she won. Aine Lawlor, whose voice you might recognise from RTÉ One and Morning Ireland, was not the kind of President that the engineers had such contempt for. Rather for those who, according to D’Arcy, didn’t really have the students’ best interests at heart and were purely “paving the way for future political careers”.

The engineers had no small part to play in Lawlor’s success. The engineers were knocked out in the first round of voting. Aidy Aboud, now since deceased, got the most votes out of the engineers, for no reason other than having alphabetically blessed initials. Due to the fact that students apparently didn’t understand how the voting system worked, explains D’Arcy, they all voted for their serious candidate of choice first, voted the engineers two till fifty, and left their least prefered serious candidate last. This left Lawlor with an impressive majority, and effectively sabotaged what would have been a tight competition between the two serious candidates. The engineers were “blamed” for Lawlor’s win as a result, while being subject to much scolding from the SU for “trivialising the whole thing”.

Though a part of this story reveals an encouraging aspect of female representation, with Lawlor winning the election against forty-nine male engineers, it also leads one to wonder why were the forty-nine exclusively male? The women at the reunion joked that they were just not stupid enough to join in the protest, and though the forty-nine assured that it was not a conscious decision, it does reflect a barrier that women faced nonetheless. “There were so few [women] engineers in the class”, says Mary O’Halloran, an IT engineer. “We were a miniscule number.” There were 16 women out of 160 engineering students in the class of 1983. “We stuck together quite a bit, which was probably survival”, inserts Carol McCarthy, Programme Manager for Local Authority Water. “We stood out”, says O’Halloran, which was why they didn’t feel comfortable in participating in the attention grabbing campaign of the forty-niners.

Andrew Butterfield, now a Trinity lecturer in Computer Science, was also one of the engineers in the running for President in 1982. Butterfield reflects how his perception of the SU changed from his rebellious undergraduate years to when he served as a member of the College Board from 2005 to 2008. He recalled how he was consistently impressed with the SU officials’ commitment to their role as representative of the student body, how they were always on top of their briefs, and “particularly in tune with College bureaucracy”. He now admires the SU’s activism across campus. There is always a place to have a bit of “student activity” going on in college, says Butterfield. Having “young radicals who care” is something we need in our society.