In recent weeks, there have been 11 cases of bacterial meningitis, or meningococcal disease, reported to the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC), the group responsible for monitoring outbreaks of infectious diseases in Ireland. Of these 11 cases, three of those infected have died. Furthermore, many people who survive meningococcal disease are left with lifelong disabilities including amputated limbs, hearing loss, and brain damage. Bacterial meningitis is a disease with horrific effects. However, it is classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a vaccine-preventable disease; there exist effective preventive vaccines against it. These vaccines are made available to Irish infants by the HSE, free of charge. With cases of meningitis apparently on the rise, and the devastating effects of meningitis as clear as ever, many of us are left to ponder: why do vaccination rates against bacterial meningitis appear to be dropping? The answer, perhaps unsurprisingly, may have a lot to do with fake news.

About one in ten of us unknowingly harbour the nasty bug responsible for bacterial meningitis in our nose or throats, and a small number of those infected will go on to develop a pathology. Invasive meningococcal disease is most common in infants and young children. Charlotte Cleverley-Bisman became the face of a campaign to encourage vaccination against bacterial meningitis in New Zealand in 2004, when she was less than a year old. As a result of severe complications arising from her meningococcal infection, she had both arms and both legs amputated. There have been many more high-profile cases highlighted by parents of children who have lost their lives to meningitis.

“Since the introduction of the MenC vaccine in Ireland in late 2000, the rate of bacterial meningitis infections due to meningitis C dropped from 139 cases in 2000 to just six in 2014.”

The devastating effects of bacterial meningitis are clear. It is also clear that vaccination against the bacteria is an important and effective way of preventing the disease. According to the HSE, since the introduction of the MenC (meningitis C) vaccine in Ireland in late 2000, the rate of bacterial meningitis infections due to meningitis C dropped from 139 cases in 2000 to just six in 2014, a reduction of 96%. Before the introduction of this vaccine, meningitis C was a major cause of meningococcal disease in Ireland. Nowadays, most cases are caused by meningitis B. In response to this, the HSE introduced the MenB (meningitis B) vaccine for infants in 2016.

Despite the addition of effective vaccines to the childhood immunisation schedule, Ireland had one of the highest rates of invasive meningococcal disease in Europe between 2011 and 2015. In 2018, there were 89 cases compared to 76 the year before, a rise of 17%. This makes for worrying reading. This is not to sound alarmist, or to overlook the commendable efforts on the part of the HSE in achieving a marked reduction in meningitis rates between 2000 and 2014. However, the number of meningitis C cases has increased every year since then. It seems apparent that these numbers are moving, albeit relatively slowly, in the wrong direction.

The sense of frustration and dismay in response to this is understandable. Speaking recently, Dr Kevin Kelleher, the HSE Assistant National Director of Health Protection, remarked: “What I’ve got to say is we have got available the vaccines to cope with this problem. What is interesting is, after all the pressure around us getting vaccines to deal with meningitis, the uptake rates are not hitting [the required levels]”. Indeed, according to the HSE’s own figures, the uptake rates for meningitis vaccines are falling well short of targets. For example, the target uptake of the MenC booster vaccine, which has been made available free of charge to first year secondary school students by HSE vaccination teams since 2014, is >95%. For the 2016/17 academic year, the actual national uptake rate was only 84%. This represented a 3% fall from the year before. Vaccination rates are higher among infants; however, they are still below targets.

“Gone is the talk of consigning measles to the history books; instead, it is back with a vengeance.”

What accounts for the sub-optimal uptake of these life-saving vaccines, even when they are made freely available to Irish children? In recent history, there has been several high profile controversies surrounding immunisations and their supposed side effects. This began with the now-disgraced British doctor, Andrew Wakefield, who in 1998 suggested a link between the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine and autism. Despite being struck from the British medical register for unethical behaviour, misconduct, and fraud, he would have a lasting disincentive impact on MMR vaccination rates and immunisation schemes in general. Gone is the talk of consigning measles to the history books; instead, it is back with a vengeance, and there have been several high profile outbreaks in recent years.

In more recent times, there has been controversy regarding alleged side-effects of the HPV vaccine in Ireland, which is administered to prevent girls from developing cervical cancer when they are adults. These controversies have evidently led to a loss of trust in vaccines in general, leading some parents to deliberately forgo having their children vaccinated.

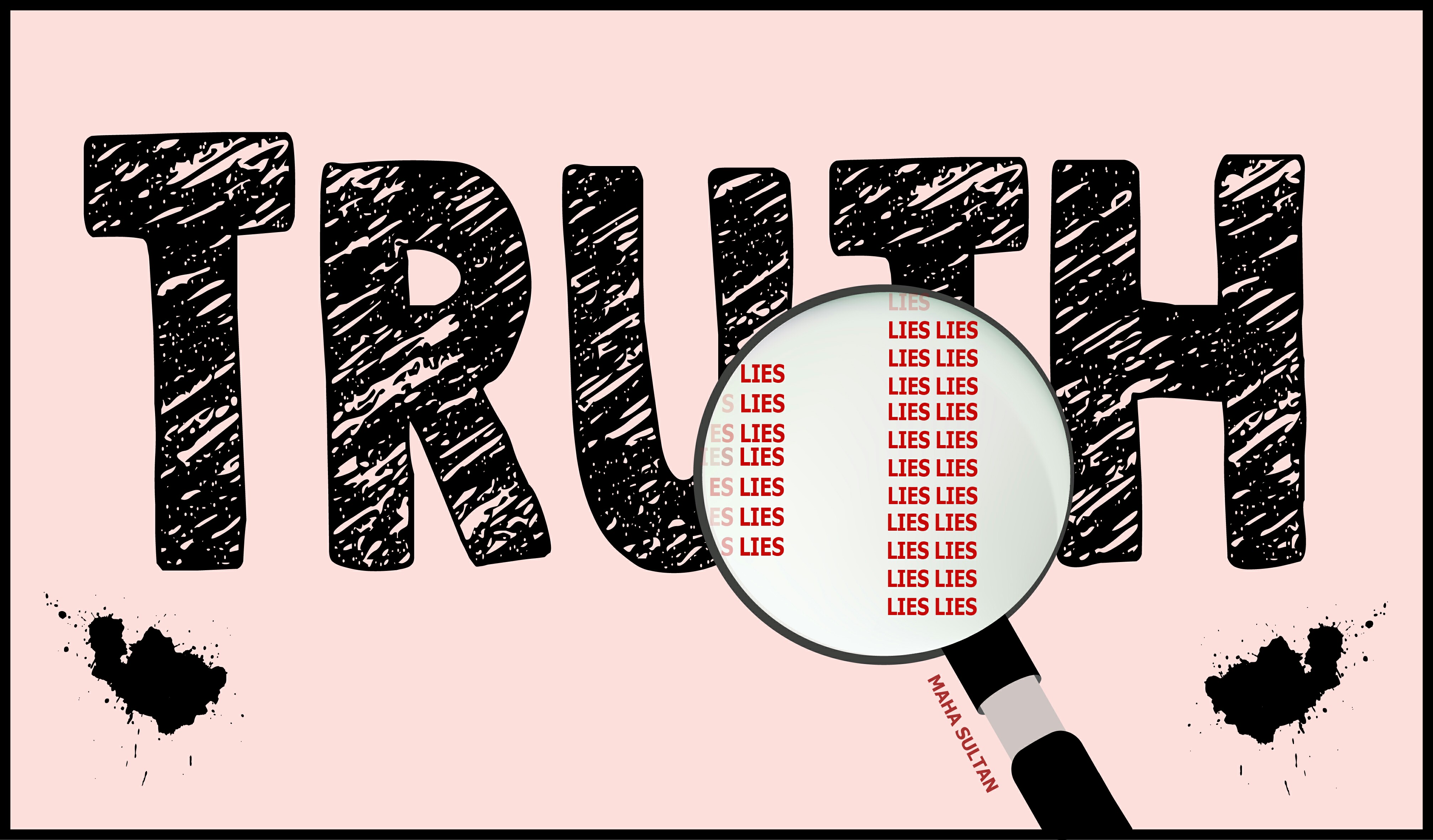

According to recent reports, 67% of US adults get their news from social media. It’s unclear how this compares to Ireland, however, the general message is clear: increasing numbers of people turn to non-traditional news outlets to inform themselves. Few people will argue that the barriers to publishing one’s thoughts and opinions for others to see and read have never been lower; with the rise of the information age, we have also seen a greater potential for misinformation and deception. This has manifested itself as the phenomenon of fake news; the editorial standards regarding a viral Facebook post are not the same as those to which journalists are held in a traditional news outlet. Fake news is nothing new, but in the digital age it has taken on new significance.

Fake news presents us with numerous challenges, and there will be no quick fixes. Donald Trump has tweeted anti-vaccine rhetoric on multiple occasions. However, prominent Hollywood liberals such as Robert De Niro and Jim Carrey also use their influence in the media to erode public confidence in immunisations, despite vocally opposing almost everything else Trump says. A 2015 study published in the journal Pediatrics found that clusters of people who don’t vaccinate their children are concentrated in liberal parts of California. Mistrust of vaccinations can be found on all sides of the political spectrum and these views are pushed by a diverse group of public figures. Therefore, few of us are immune to being influenced by anti-vaccine fake news on social media.

“On the spectrum between those who accept or reject vaccines, it is the people in between who are most vulnerable to fake news.”

A common theme among those who decline to have their children vaccinated is that of “vaccine hesitancy”. According to an article in the journal Nature in 2011, up to one-third of parents in the USA, UK and Australia report concern about the recommended vaccine schedules in their countries. These people are neither outright anti-vaccination or pro-vaccination, but somewhere in the middle. They often choose to avail of some vaccines, but express doubt in and delay, or forgo others. People who are vaccine-hesitant often lack trust in the safety of vaccinations, or doubt their value, rather than being convinced that vaccines are downright harmful. On the spectrum between those who accept or reject vaccines, it is the people in between who are most vulnerable to fake news. These “fence-sitters” are also most in need of clear, factual information about the importance of immunisation against vaccine-preventable diseases such as meningococcal disease.

If we are to address vaccine hesitancy and improve the uptake of life saving vaccines such as those against bacterial meningitis, the concerns of these parents must be relieved. Open, accurate and honest information must be made easily accessible for these parents, in order to counteract misinformation posted online. Helping these people regain trust in vaccination is an important step to improving uptake rates, and is a challenge facing our health system. The personal tragedies arising from the recent spike in bacterial meningitis cases also serve as a stark reminder of the deadly consequences of anti-vaccine fake news.