Yesterday evening, Trócaire representatives Emmet Sheerin and Garry Walsh captivated a student audience with insights from their time working in and photographing underprivileged areas of the world. The workshop was a collaboration between SUAS and Dublin University Photography Association (DUPA), and explored the ethical considerations of photographing residents of underdeveloped countries.

Both Sheerin and Walsh come from backgrounds rich in human rights activism. Sheerin has been working for five years within Trócaire, striving to mobilize the Irish public to take political action for change and he previously served as a human rights observer in Palestine. Walsh also works for Trócaire and has spent the last eight years documenting their actions around the world. He has managed development projects in Myanmar and previously spent five years working on the Israel Palestine project.

The work of both men centers around visual media. Photography and videography have become modern essentials to the circulation of information about human rights abuses. However, as a relatively invasive line of work, Sheerin and Walsh’s jobs require special ethical considerations to preserve the dignity of their subjects. “Taking an ethical approach is really essential to our work,” explained Walsh. For Walsh, his desire for ethical responsibility stems from a mistake made on his own part during his foundational years as a volunteer in Ethiopia. As a photo of young Walsh holding an Ethiopian boy flashed onto the screen, Walsh explained the phenomenon of the “white savior” volunteer who, often unknowingly, uses photos of himself with an underprivileged child to make himself look heroic.

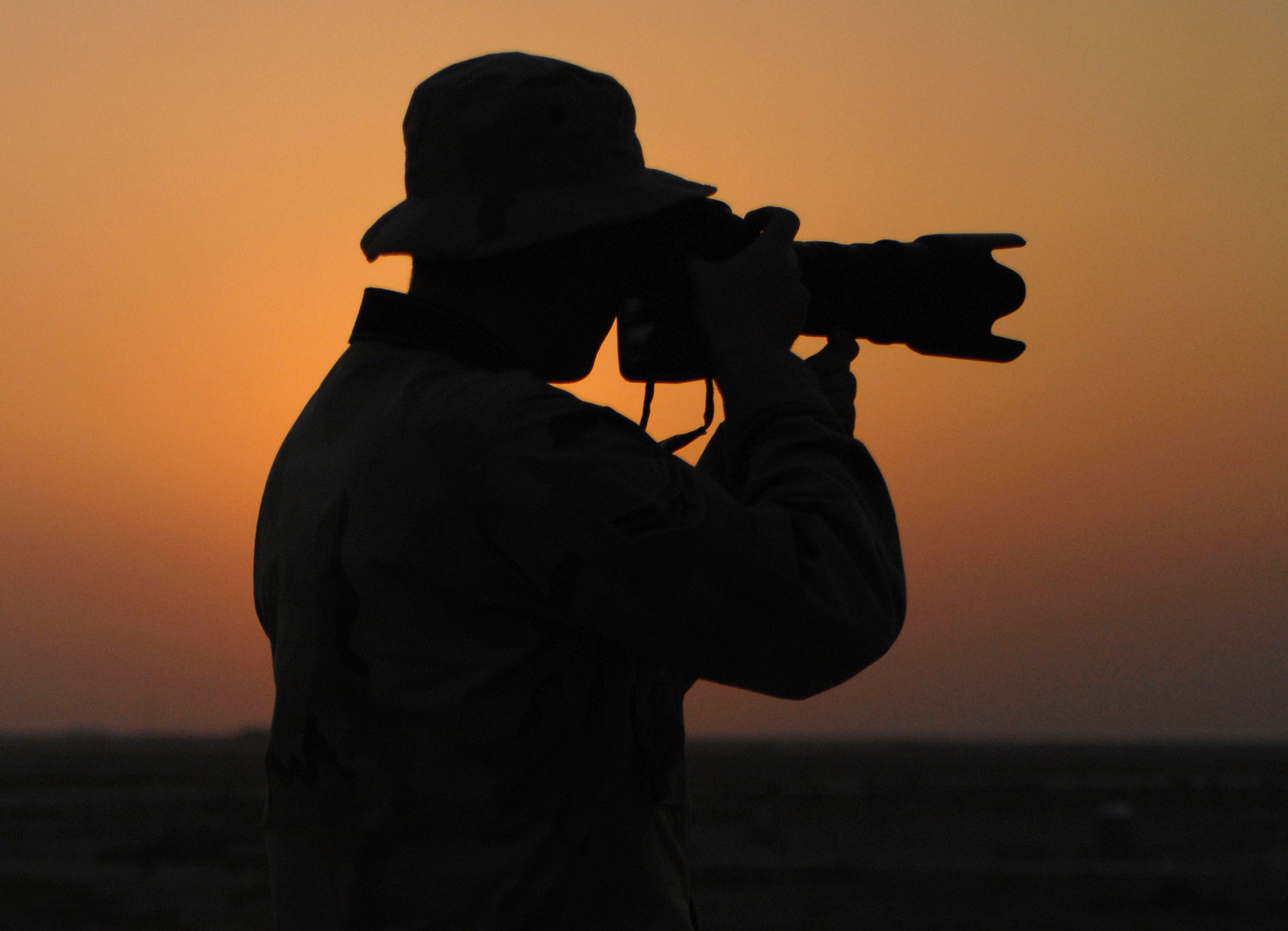

The creation of the modern camera was paramount to the divulgence of human rights abuses around the world, as the camera allowed these abuses to be more clearly and effectively communicated with outsiders. “Photography [is used] as evidence of abuse”, Sheerin asserted, citing a photo of a Guatemalan protest as an example. “Photography can position you with a community”, Sheerin explained in reference to the photo, which is from the point of view of a protestor, allowing a viewer firsthand insight into the event itself.

The power of photography to incite change is uncanny. However, Sheerin warned, “we need to be careful about saying photographs alone do this” as photographs “are only a small part of the puzzle” of human rights work. Photographers cannot get overzealous in estimating the impact of their photos alone; oftentimes photographs are only the first step to visible change.

While human rights abuses have been captured on camera for years it is only recently that the ethical considerations of such work have begun to be taken seriously. The Dóchas Code is a code of conduct on images and messaging established by Dóchas, an organization for international development organizations in Ireland, that coordinates and sets professional standards for human rights organizations. The Dóchas Code comprises a “useful set of standards for anyone who might be going out in the developing world”, stated Walsh, and influences “how we represent the people we photograph”.

The code itself is based on the three principles of “respect for the dignity of the people concerned, belief in the equality of all people, acceptance of the need to promote fairness, solidarity and justice”. Walsh summarised the code as a resounding reminder of the impact of photographers can have on local people’s lives, and to illustrate “your own power when you’re taking a photograph”.

Walsh and Sheerin highlighted numerous tips on how to protect the privacy and comfort of the subjects of the photographs. Walsh encouraged the audience to take empowering photos of locals rather than victimizing ones, to convey them as “agents of change themselves” instead of as helpless casualties. This aids in dismissing the “white savior” stereotype by allowing locals to save rather than be saved. Both men urged the audience to “try and represent the world as it is and not to reinforce stereotypes,” and to make sure a range of locals are represented, such as both women and men, the young and the old and those with different beliefs. The importance of consent and of protecting people’s identities in sensitive situations were also emphasised as important things to keep in mind when photographing.

Sumud, Everyday Resistance, a short film by Sheerin, was shown to the audience to reinforce the advice given by the two men. Centering on the everyday lives of Palestinians in the West Bank who endure daily hardships at the hands of the Israeli military, Sheerin explained how the film captures the resilience of local residents, specifically women, who are steadfast in their way of living. The film, ethically shot and expertly edited to evoke strong emotional responses, was a testament to the human rights abuse occurring every day in parts of the world.

Visual media is a powerful tool in conveying the problems this world faces but it is paramount that these issues are represented in a way that is ethical and fair. Sheerin finished with a simple yet often forgotten fact in human rights photography: “It’s not always just about showing the problem, showing the oppression, showing the violence – It’s about showing the people as well.”