Being successful in sports isn’t easy. You’re up against a consort of talented people who seem to be stronger, faster, and more skilled than you are. As more and more young people get involved in sports, the competition is fiercer than ever. Sport in college can be a hobby, but it can also be something people dedicate years to and hope to have a career in. The willingness to train harder and make more sacrifices becomes so ingrained in some athletes that they will do anything, including doping, to outperform their opponents. Doping, referring to the use of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs), provides a way to improve an athlete’s performance and increase their chances of winning. Is this a phenomenon brought on by advances in chemistry? Or is it due to sport becoming polluted with too many talented athletes? Or is it a reaction to pressures surrounding body image and pressures to secure the financial benefits that come with the fame sports careers bring?

The Olympics is arguably the most famous sporting event in the world. It has its birthplace in Ancient Greece, as does doping. Ancient Greeks took part in a range of sports and used herbs, alcohol, certain foods and hallucinogens to enhance their performance. The same is done today, though admittedly with more sophisticated techniques. Most popular amongst young people is use of steroids which boost muscle mass, but other methods used by professional athletes include increasing oxygen levels by removing their blood so they can inject it into themselves again on the day of a competition.

“One in five people aged between 18 and 34 would consider taking steroids.”

Yet even outside of the sports community, it seems to be increasing as a problem. A Pediatrics Review in 2012 highlighted a survey of 16,500 teenagers done by the National Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System that discovered 2.7% used steroids in 1991, and that there was an increase by 2009 to 3.3%. More recently, the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) revealed that one in five people aged between 18 and 34 would consider taking steroids.

With PEDs running rampant in sport the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was established in 1999, in the hopes of controlling doping in sport. It don’t just test for PEDs, but it also researches their effects and how to better spot them. It also does it across the world, uniting sports players under one umbrella of rules. However, WADA is not perfect with many accusations of corruption, namely in relation to Russia. It has struggled in the past to carry out investigations in Russia and have only recently turned to the prominent doping scandal in that country. In 2015, the president of WADA, Sir Craig Reedie, wrote an email to the then sports minister Vitaly Mutko saying that he valued their relationship and that “there is no intention in WADA to do anything to affect that relationship.” And while Reedie has since said that he did nothing to interfere with the investigations and there have been improvements in the scrutiny placed on Russia, with a potential ban from the Tokyo Olympics on the cards, it’s clear there is a lot of work to be done to obtain true transparency.

Arguably the world’s most famous doping scandal centred around Lance Armstong, a professional cyclist. In 2012, he was found guilty of using PEDs, namely erythropoietin, several steroids and blood transfusions, despite denying the accusations for many years. He received a lifetime ban from competitive cycling and was stripped of all of his awards including seven Tour de France titles and his Olympic Bronze Medal. More recently, Aphiwe Dyantyi, a rugby player for South Africa tested positive for a banned substance, though he denies deliberately doping. This scandal saw him excluded from the Springboks current Rugby World Cup campaign. This raises the question of whether current approaches to preventing doping are effective. Despite professional players undergoing regular and random testing it does not seem to deter the temptation to dope.

Currently, professional athletes are tested randomly for doping. Should university and school students be subject to the same scrutiny? Recently Brian O’Driscoll advocated for testing of underage players, saying: “If I was the parent of a 15 or 16 year-old, skinny kid that was being told that they are not going to make it because they are not big enough, and there are temptations, then I would want my kid to be tested.” Trinity Rugby’s Facebook page outlines its anti-doping stance in its about page, suggesting that a firm stance on drugs is part of its ethos. Certainly, instances of doping in Trinity, or colleges in general, are not well documented (if there are any). A sensitive topic in sport, it is something no athlete wants to be accused of.

“Zero Gains was a campaign launched to raise awareness about the damage steroids can do.”

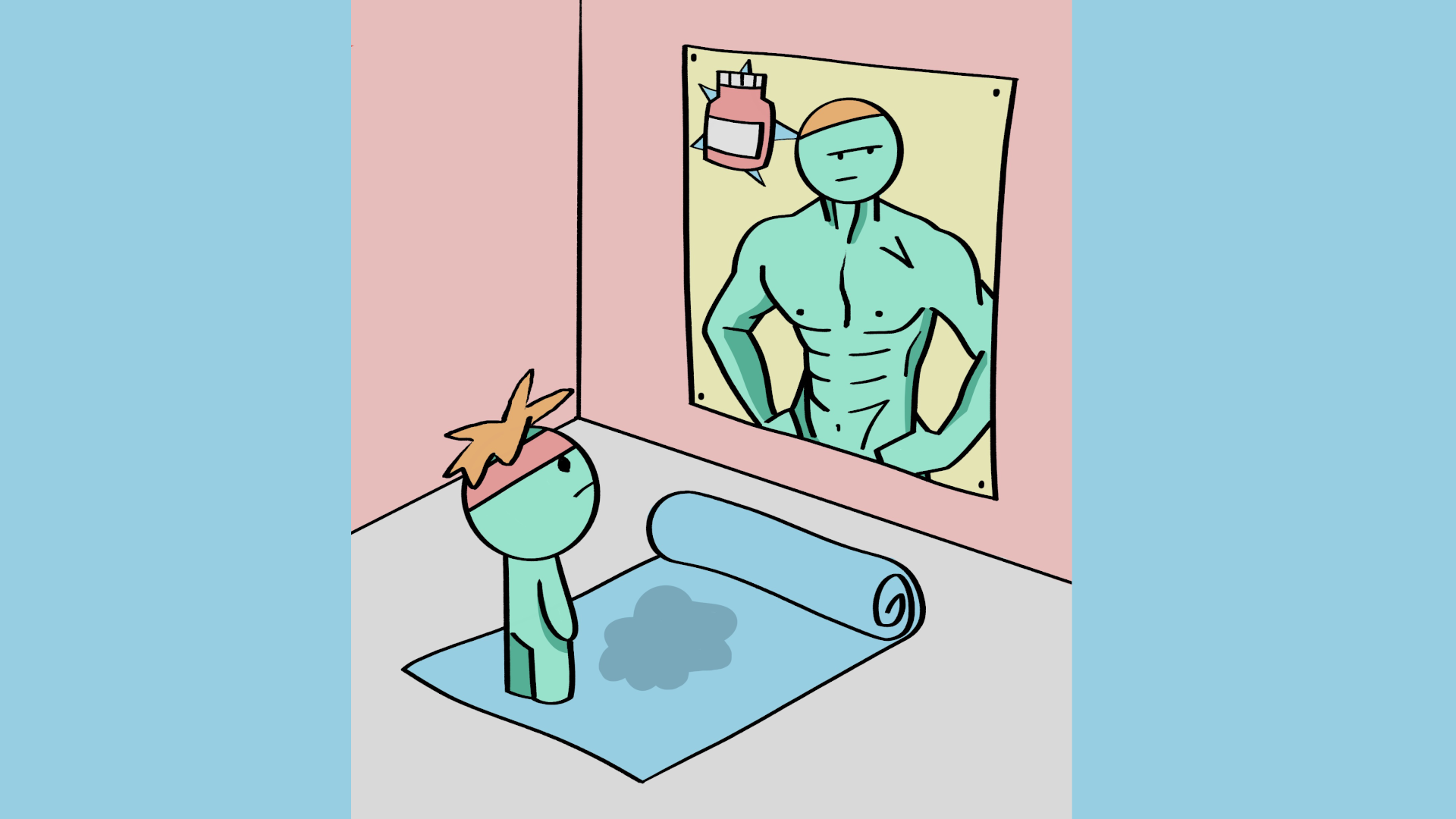

With so much at stake, it may seem bizarre to risk it all considering any athlete could be tested, and if found guilty of using PEDs could face a ban or suspension. A sporting career is only ever viable for a finite period so time is of the essence. A three year suspension can be the difference between success and failure. The Pediatrics Review in 2012 expressed concern for the increased use of PEDs in young people, highlighting they are already at risk of drug use due to an invincible attitude. The possibility that the reason for doping is more than competitiveness was also explored. Many sports players are expected to have a certain physique. PEDs can be an aid to those who succumb to the intense scrutiny they are under in either maintaining a low weight, or maybe even gaining muscle. Even for those outside the sporting community, PEDs can market themselves as an opportunity to emulate the physique of an athlete.

While there have been arguments to allow athletes to dope as much as they want, the side effects of PEDs cannot be ignored. Zero Gains was a campaign launched to raise awareness about the damage steroids can do if not prescribed by a medical professional. There are many health risks including infertility, problems with your heart and liver as well as “roid rage”. “Roid rage” is the term given to the noticeable changes in personality and behaviour when steroids are abused. Studies have predominantly linked steroid abuse to increased aggression and irritability, with some saying that it also increases the risk of anxiety. The dangers are clear and are not something that ought to be ignored. In 2017, Luke O’Brien May, a young sportsman, died from the use of steroids while taking his Leaving Cert.

Using PEDs in competitive sports is simply cheating. Using PEDs at all is incredibly dangerous. But despite the name, PEDs are becoming less and less about performance and often are being used to help young people improve their body image. Students in college and in school are already bombarded with adverts depicting the “perfect” body. The promise provided by steroids and PEDs is not just a chance to gain the glory, fame and money that some athletes possess, but a chance to mould your body. But it is a promise that risks the integrity of sports and the health of our future sporting stars.