“Knowing what you own is the first step to aligning your investments with your values,” according to the Investigate Project, a research and information centre that seeks to learn how companies profit from and support state violence, and urges the public to investigate the human rights violations hidden in their investments. Students have continuously called upon Trinity to realign its investments and partnerships with their moral standards as a university in recent years, as Trinity’s business ventures come to light.

The student led Fossil Free TCD campaign, successfully called upon Trinity to divest from the fossil fuel industry in 2016. Trinity’s investment in the fossil fuel industry clearly fell out of line with the university’s aspirations to be a leader in sustainability and climate solutions. It seems many of Trinity’s investments and partnerships still have yet to be reconciled with its ethical pursuits.

The Commercial Revenue Unit (CRU) was established in 2014, and is responsible for making contracts and partnerships for the College. According to its website, CRU aims to “secure and support opportunities to drive revenue streams for Trinity,” in order to further its status “as a celebrated student-centred campus and globally recognised university tourist destination”. Trinity’s main contracted partners are Bank of Ireland, Coca-Cola, Aramark and Sodexo.

The Aramark off our Campus campaign was launched last year by Trinity graduates Stacy Wrenn and Jessie Dolliver. Aramark is an international food and services provider as well as a government contracted operator of Direct Provision centres across Ireland. Aramark received a €5.2 million investment from the Irish government in 2016 for servicing three direct provision centres – Kinsale Road in Co. Cork, Lissywollen in Co. Meath, and Knockalisheen in Co. Limerick.

The United Nations Refugee Agency has repeatedly called for urgent reform of Ireland’s system of processing asylum seekers, and has been condemned by many as an inhumane and cruel process. In 2015 residents carried out a brief hunger strike in the Aramark run centre in Knockalisheen Co. Limerick, after some were hospitalised as a result of poorly produced food. A year earlier a hunger strike occurred in the Lissywollen Accommodation centre in Athlone Co. Meath, also run by Aramark, due to small portion sizes, poor hygiene, and living standards.

Aramark operates in Dundrum Town Centre and owns Avoca. It operates in one restaurant on campus, Westland Eats. The Aramark off Our Campus campaign was supported by the TCDSU council last year and soon spread to the University of Limerick and UCD. Through a series of boycotts and protests, students behind the campaign demanded Trinity end its partnership with Aramark at the earliest break in their contract, and replace the contract with another company that does not support the Direct Provision industry.

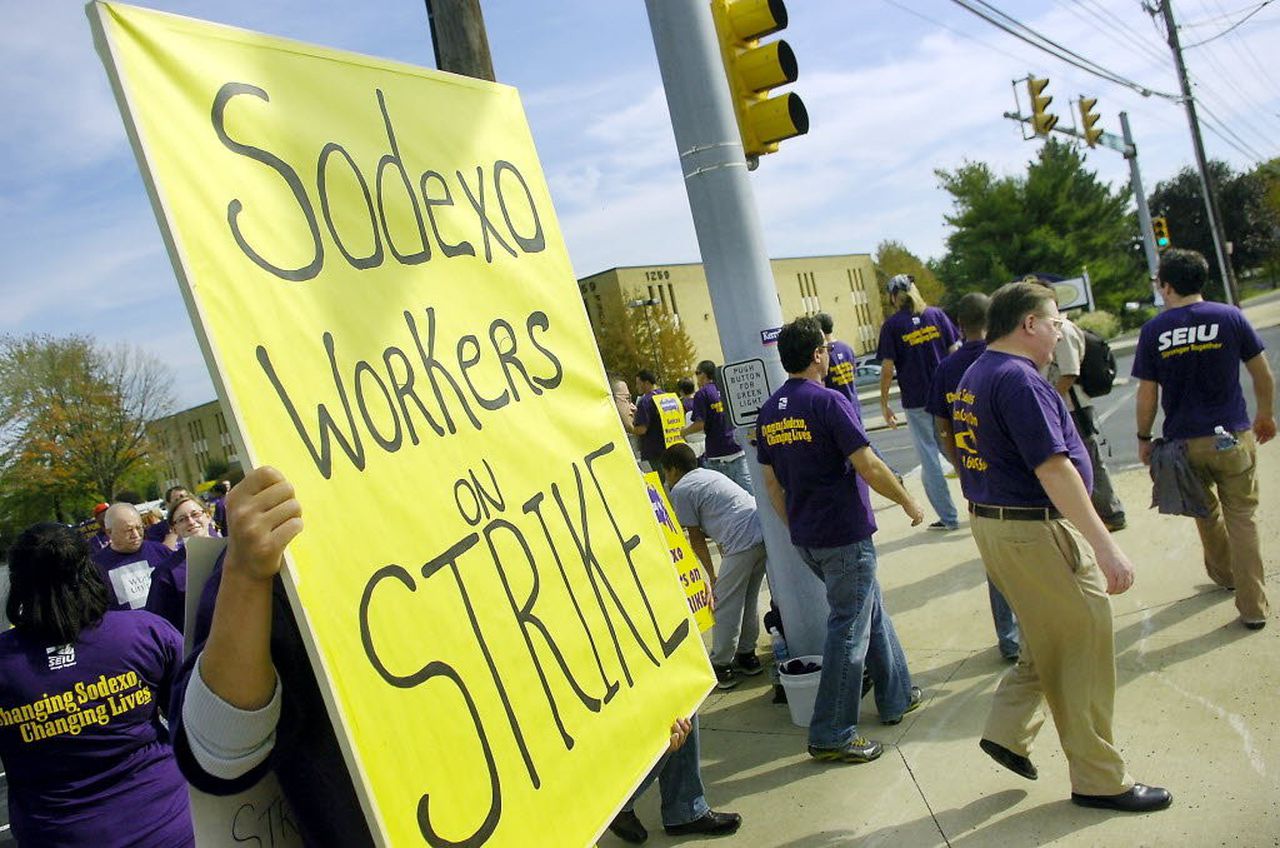

Aramark off Our Campus petition holds 844 signatures, all who believe that “by continuing their contract with Aramark the board of Trinity College Dublin are … ignoring the voices of some of the most vulnerable people in society.” Trinity’s contract with Sodexo is set to continue until 2023.

“In seeking to work with catering partners, the College is driven by the need to provide the best student and staff experience in its catering outlets while at all times ensuring that we continue to support the academic and research mission of the college through commercial funding,” says Moira O’Brien, Catering Manager of Trinity Catering Department. Trinity Catering runs eight food outlets on campus.

“The College followed all appropriate governance in awarding these contracts” says O’Brien. Coca-Cola’s partnership with the College requires the Buttery, TCD Student Union shops, the Dining Hall, the Pav and Westland Eats to stock predominantly Coca-Cola Company bottled products, and in return a significant amount of the revenue from the deal has been channeled towards Trinity Sport. Last year, the independent cafe in the Science Gallery, Cloud Picker, moved out of Trinity after refusing to comply with the terms of Trinity’s contract with the Coca-Cola company. Cloud Picker was once described as “the best science gallery cafe of any science center in the world,” by The Irish Times.

Sodexo provided a fully fitted new catering facility in the new Business building and was awarded a contract with the 300 seat Forum restaurant last year. The multinational company Sodexo was awarded a contract to operate the Perch Cafe in 2016, and will be operating the Forum restaurant until 2030. Sodexo is a French multinational company and is one of the largest food services and facilities management companies in the world. Sodexo operates in 72 countries and employs approximately 430,000 people. The company provides services such as food, security, site management, and maintenance for a wide range of institutions, such as: hospitals, schools, universities, care homes, military bases and prisons.

“Sodexo partners with nearly 30 universities in the UK and Ireland and at Trinity, as with all sites that we operate, Sodexo is committed to the highest standards of food safety and employee welfare,” comments Barbara Elliot to Trinity News, a spokesperson on behalf of Sodexo Ireland. “At Trinity and on all our sites, Sodexo Ireland is fully compliant with all relevant Irish employment health and safety and food safety legislation,” Elliot ensures.

Sodexo Ireland has been voted one of the Best Large Workplaces in Ireland in 2018 by the Great Places to Work Institute. The company was one of the 11 founding signatories of the country’s first Diversity Charter and was voted one of the Top Ten Places to Work for LGBT Equality at the Irish Workplace Equality Awards.

“Sodexo fully supports Trinity’s commitment to a single use, plastic-free campus and doesn’t stock any non-biodegradable or non-recyclable products and cutlery,” Elliot relates. “At Trinity, we work closely with local suppliers to offer food that is fresh, tasty and ethically sourced, whilst still competitively priced.” Sodexo is also committed to reduce its carbon emissions by 34% by 2025 and has joined the Science Based Targets initiative, the global movement of leading companies aligning their businesses with the most ambitious aim of the Paris Agreement, which is to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Sodexo Ireland has been widely recognised for its many commitments to sustainability, equality and employee welfare. However, a variety of scandals and controversies have still considerably stained its image and compromised its integrity in the eyes of the public.

In February 2013, Sodexo withdrew all frozen beef products from its catering operations in the United Kingdom when some tested positive for horse DNA. Three weeks after this became known to the public, Vestey Food Group, admitted that it had supplied horsemeat to Sodexo.

Sodexo was also implicated in Germany’s biggest outbreak of food poisoning in 2012, when at least 11,200 school children in almost 500 schools and daycares became ill, and at least 32 hospitalised. Sodexo apologised and vowed to compensate the victims, according to Reuters, as the outbreak was found to have been caused by its frozen strawberries.

Sodexo has a long history of involvement in the private prison industry, having held significant stakes in Corrections Corporation of America, now CoreCivic, one of the world’s largest private prison companies.

Sodexo has a long history of involvement in the private prison industry, having held significant stakes in Corrections Corporation of America, now CoreCivic, one of the world’s largest private prison companies. Sodexo pulled out of its stake in the company following mounting pressure from universities in the United States who began cancelling its food services contracts with the company.

Sodexo still manages private prisons under its subsidiary Sodexo Justice Services. The company is still the operator of four out of 14 privately-owned prisons in the United Kingdom and Scotland, including HMP Bronzefield, HMP Forest Bank, HMP Peterborough, HMP Addiewell and HMP Northumberland. There have been repeated reports of abuse, neglect, and torture in these prisons in recent years.

The prison-industrial complex is a phenomenon in which prisons are licensed by the government to private companies in order to make a profit. While private prisons companies claim to lower the national relapse rate through correctional services, some believe that these companies’ profit model is fundamentally unethical, theorising that the company’s profit model is an incentive to keep as many people in custody for as long as possible, in order to maximize revenues. The profit model of private facilities is believed to be antithetical to the social goals of rehabilitation as it is driven by the incentive to cut costs, and may lead to inadequate staff training, a high turnaround for guards, and poor services.

On the other hand, private companies could presumably be more effective at lower costs, and indeed the experience of privatization has not been negative in all cases. “Our focus is on reducing reoffending through rehabilitation,” says Elliot. “We support people in our care to change their lives for the better by providing opportunities for purposeful activity and employment skills, education and rehabilitation support services.” Sodexo assures its observance of ethical principles due to the fact it only operate prisons “in democratic countries that do not have the death penalty and where the ultimate goal of imprisonment is prisoner rehabilitation.”

In October 2019, a woman gave birth alone in her cell at HMP Bronzefield. The baby died at the prison. Surrey police stated that: “The death is currently being treated as unexplained and an investigation is continuing to establish the full circumstances of what happened.” Four women have died at Bronzefield since July 2016. Inmate Natasha Chin was found to have died in her cell in 2016, less than 36 hours after arriving in the prison. Last year an inquest reported that the death was caused by a systemic failure through poor governance which led to a lack of basic care” and was “contributed to by neglect”.

HMP Northumberland was privatised in 2014 and is now run by Sodexo Justice Service. Sodexo pledged to save the taxpayer £130m over 15 years. 200 jobs, including 96 prison officer posts, were cut according to the BBC. A 2017 BBC documentary, Undercover Panorama, revealed that Northumberland prison had “descended into chaos, with failing alarms, prisoners calling the shots and a troubling drug problem sweeping its corridors.”

This year, the UK Ministry of Justice criticized Sodexo for failing to prevent repeated and systemic breaches of the human rights of women held at the Peterborough prison.

This year, the UK Ministry of Justice criticized Sodexo for failing to prevent repeated and systemic breaches of the human rights of women held at the Peterborough prison. These breaches included illegal strip-searches at the jail, including of menstruating and transgender prisoners. Sodexo said it had since conducted a review of its strip searching procedures and had introduced a number of new safeguarding measures at HMP Peterborough.

Under the name of UK Detention Services Limited, Sodexo was involved in immigration detention centres in the UK until 2006. Namely, that of Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre, which is the largest detention centre in Europe.

Men, women and children, the elderly and people with disabilities can be held against their will in immigration detention centres pending a final decision on their asylum appeal, which can result in their removal from the country. Multiple deaths and reports of mistreatment at Harmondsworth has led to the Centre being described by the Guardian as “worse than prison.” The main detention centres in the UK are now run by other multinationals Mitie, Serco and Geo Group. These companies, like Sodexo, also have a wide variety of incomes from catering providers to suppliers of electronic tagging devices for offenders and asylum seekers. Private prisons and immigration centres are clearly lucrative business ventures for huge multinationals, profiting off the incarceration of some of the most vulnerable people in society, but at what cost?

“We have opened ourselves up to these corporations which it has really compromised our stance and influence having any type of moral stand as a university,” says Jessie Dolliver, Trinity graduate and End Direct Provision activist. The reason that College has started getting contracts with Sodexo and Aramark is “to save money,” and according to Jessie Dolliver, “it’s not worth it.”

…the longer we support these companies like Sodexo and Aramark, the more social licence and allowance we’re giving them.

“Having a university is a bastion for moral and philosophical thinking and it should be guiding our society,” says Dolliver. “Trinity’s corporatisation is just kind of completely throwing that out of the window.” Dolliver believes that: “the longer we support these companies like Sodexo and Aramark, the more social licence and allowance we’re giving them.”

According to Trinity’s Strategic Plan laid out in 2014, “Every great advance that Trinity has made has been in partnership with others: it is partnerships that enable Trinity to enhance its standing as a place of learning, and Ireland’s reputation as a civilized society giving equality of opportunity to all with the talent and ambition to succeed.” Trinity’s recent corporatisation has seen the increase in ambitious partnerships and resourceful investments in recent years. However, it forces us to reconsider what we wish to stand for as a university: whether we can still meaningfully pursue University of Sanctuary status while we support a company that incarcerates asylum seekers and whether we can still be considered to contribute to “Ireland’s reputation as a civilized society” when endorsing companies that perpetuate a consistent maltreatment of some of the most vulnerable in society.

“Regarding the criticism,” says O’Brien, “the involvement of Aramark in Direct Provision centres is based on a government awarded contract.” CRU and College do not claim any responsibility to speak out against Direct Provision Centres as long as the government stays silent. So, who holds the agency to uphold our values as a society? Is it the government which condones? The company which violates? The university that endorses? Or maybe, it’s the student who remains complicit.