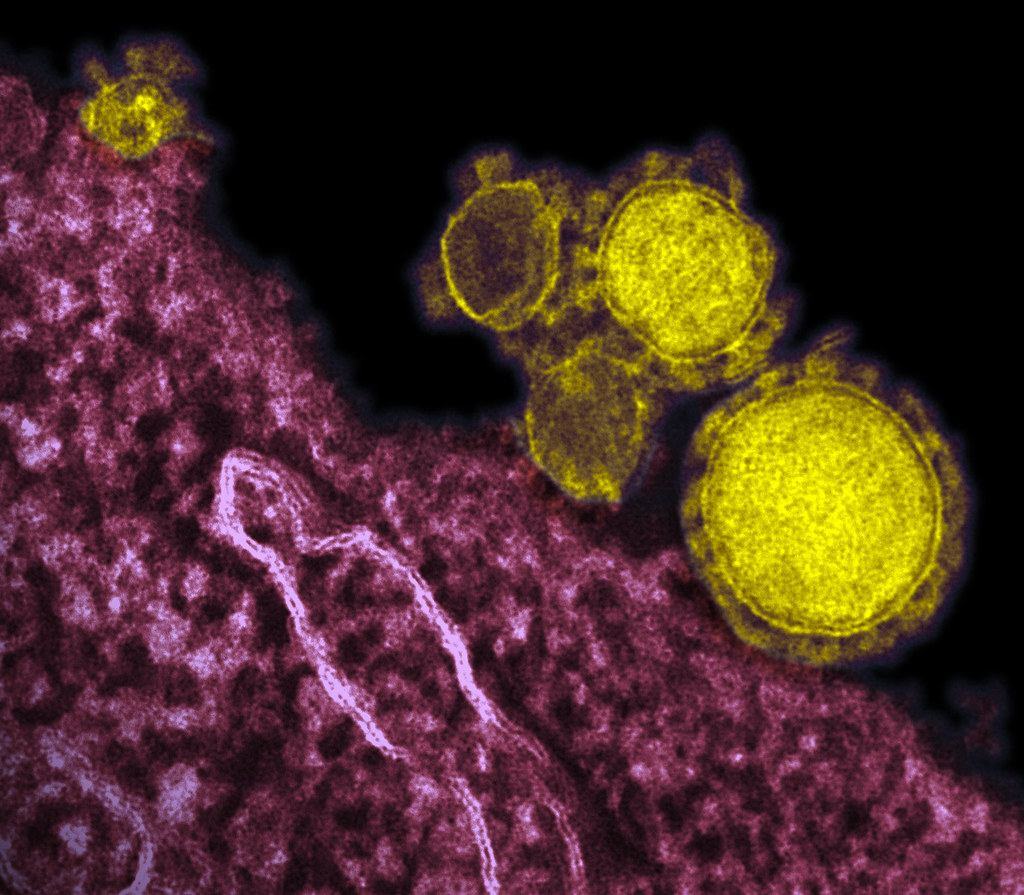

The Coronavirus isn’t named after a beer or the band, but is likening to a crown from the latin corōna a “garland worn on the head as a mark of honour or emblem of majesty, halo around a celestial body, top part of an entablature” (Merriam Webster) – the family of viruses so called for its spike shape when viewed under the microscope.

But why has this ‘royal’ virus dominated the headlines, and how is it spreading? The World Health Organisation’s decision to declare the novel Coronavirus a worldwide emergency has caused equal measures of concern, criticism and praise. But what does this mean? Understanding this ‘novel coronavirus’ (so called because it’s so new it has yet to have a name like its sisters, SARS and MERS) is key among reports of bullying and racism, fear of disease and the College decision to withdraw students studying abroad in China.

Some seem to be indulging in a possible apocalypse, with iTunes reporting the film ‘Contagion’ as receiving massive boosts to their sales. With over 400 reported deaths in a roughly eight-week time frame, it would be inhumane to dismiss concerns as pure speculation. Others feel not enough is being done to prepare for a disease that the University of Hong Kong has commented may be severely underreported.

“With xenophobia being reported worldwide in school grounds and workplaces alike, unpacking criticisms of China from racism and its social ramifications is paramount”

Disputes arise here too, as questions of a potential anti-Chinese sentiment arise. Many have been highly critical of the Chinese government’s handling of the situation. But with xenophobia being reported worldwide in school grounds and workplaces alike , unpacking criticisms of China from racism and its social ramifications is paramount. To do this, understanding what the virus is and how it functions needs to lead the way.

With a case fatality rate between two and four per cent, anywhere between one in 25 and one in 50 infected are predicted to die from the disease. Compared to the ‘normal’ or seasonal flu at less than one in 10,000, the difference is clear. With that said, it has been commented that these early figures may be inflated, as only severe cases have been noticed. If this is so, the case-fatality rate would be much lower. Equally however, 25% have also been reported as “seriously ill”, with the long-term consequences not understood as of yet. Further, every person who gets it is predicted to infect 2.5 people without intervention.

This is where both local and international interventions come into play. Trinity College has been astute in their reaction, following the guidelines of the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and calling its students and staff back from China. Including a Chinese translation of the email, guidelines were sent out relating to how to respond to symptoms, when and if quarantine is necessary, and guidelines for travel to China (don’t, if possible).

Further, the Science Gallery hosted a ‘Rapid Response’ briefing on the disease, outlining the science of the virus and discussing implications (much of which information this article is derived from). Dr. Cillian De Gascun (Director at National Virus Reference Laboratory at UCD), Dr. Nigel Stevenson (Assistant Professor in Immunology at TCD), Dr. David McGrath (Medical Director of the College Health Service) and Dr. Karina Butler (UCD Clinical Professor of Paediatrics, President of the Infectious Disease Society of Ireland) all gave valuable insight to a crowd both panicked and interested in the Paccar theatre.

Four of its sisters are no more than the common cold, leading to sniffles and an annoying cough. SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) proved more deadly than these. MERS infected approximately 2,500 people in 2012, of which about 858 died, yielding a much higher case fatality rate of 35%. With that said, numbers of infected by its sister MERS already pale in comparison to the novel Coronaviruses 20,000 and counting since its emergence in early December.

Understanding how diseases spread is key. A virus relies on its host in order to replicate. If it kills it too quickly, it will find it difficult to spread and the captain goes down with the ship. This is why Ebola struggled to maintain in human populations. While the virus was contagious, hosts often died too quickly for the virus to get a hold on humanity.

Herpes, on the other hand, often remains dormant in the human system for years, causing few flare-ups and pesky cold sores. This is its key to survival however – passing and replicating from person to person. Like a frustrating guest, it may cause issues from time to time, but never enough to break the living agreement.

As the coronavirus is thought to have originated in bats, the winged mammal and virus have co-evolved to have few, if any negative health consequences (snakes as the species-of-origin has also been reported, but this study has since been critiqued and no single answer is definitive as of yet). In the evolutionary timeline, bats have been around a relatively long time, as far as mammals go. When viruses mutate and change host however, the new host (in this case, humans) will often be unequipped for the pathogen.

It’s the difference between having dinner with a spouse, and randomly finding yourself on a blind date – there’s no prior expectation, neither party have coping mechanisms specific to the other, and no one has any idea how it will end. In the case of the Coronavirus, officials are gathering as many statistics in order to ascertain details such as how contagious it is, how it spreads, how many are seriously injured by it, and how best to implement a vaccine.

One of the most important aspects of understanding the disease was mentioned by De Gascun however, which was our tendency to anthropomorphise the virus in order to understand its ‘behaviour’. The virus isn’t a harmful, miniature crown. It isn’t a frustrating houseguest, nor is it a bad blind-date. These analogies are useful in thinking of a world that is microscopic and often seems closer to science-fiction, but remembering that the analogies are just that is important.

And just as the virus isn’t ‘clever’ in its action or ‘aggressive’, neither is it ‘Chinese’ beyond the happenstance of where it geographically originated and the attempts to restrict its movement. True, using this as an example to better fine-tune public-health policies is a must. Addressing censorship regarding the outbreak, treatment of citizens and international discourse of human rights is essential, and China is no more immune to challenge than any country. Yet labelling and conceptualising the disease as ‘Chinese’, and harbouring irrational resentment,fear and racism must be put to bed. Ethnically Chinese living in Ireland are no more likely to be harboring the virus, or at fault for travel precautions than any other citizen.

Hoping to provide some insight into Ireland’s place in the epidemic, Dr Nigel Stevenson said the “government need not be complacent “We need to learn from other countries, what they’re doing. If we have a few cases, we will cope with that. Would we cope if it’s the same situation as China? I don’t think Wuhan is coping either, but look what they’re doing, they’re making two huge hospitals.” Placing it in the context of Ireland’s inability to provide space in our hospitals as is, the nearly-full Science Gallery auditorium laughed nervously.

“There shouldn’t be a freak-out. We need to have a plan and not be complacent, but there’s no need to sensationalise it yet”

“The reality is though,” Stevenson concluded, “is that it’s so unlikely and there shouldn’t be a freak-out. We need to have a plan and not be complacent, but there’s no need to sensationalise it yet.”

The advice given by college and health authorities echoes this, and seems to quell the apocalyptic panic behind the virus. Wash your hands with soap, cough into the crook of your elbow and avoid contact with those with cold or flu symptoms. If you suspect that you may have symptoms, you are advised to phone into your GP, rather than risk further infecting germ-prone waiting rooms.

Those mass-buying health masks usually designed for construction sites probably aren’t as health-savvy as they seem, as without proper fitting, the masks are likely to be ineffective at keeping the virus out. With that said, there are two uses to these: stopping the spread of infected water droplets if you are infected, and making you more aware of (not) touching your face and mouth. The reminder of the need to be consciously clean is one of the keys to good health.

While no cases have yet been reported in Ireland, precautions and public health knowledge and rapidly being spread, particularly after the WHO’s decision to classify the outbreak as a global emergency. These tips may seem paltry in the context of a ‘global emergency’, but effective care is often just that – moderated. On the other hand, irrational xenophobia, hate and fear represent an entirely other epidemic that infects our language and views, without the tell-tale signs of a cough to remind us to be cautious.