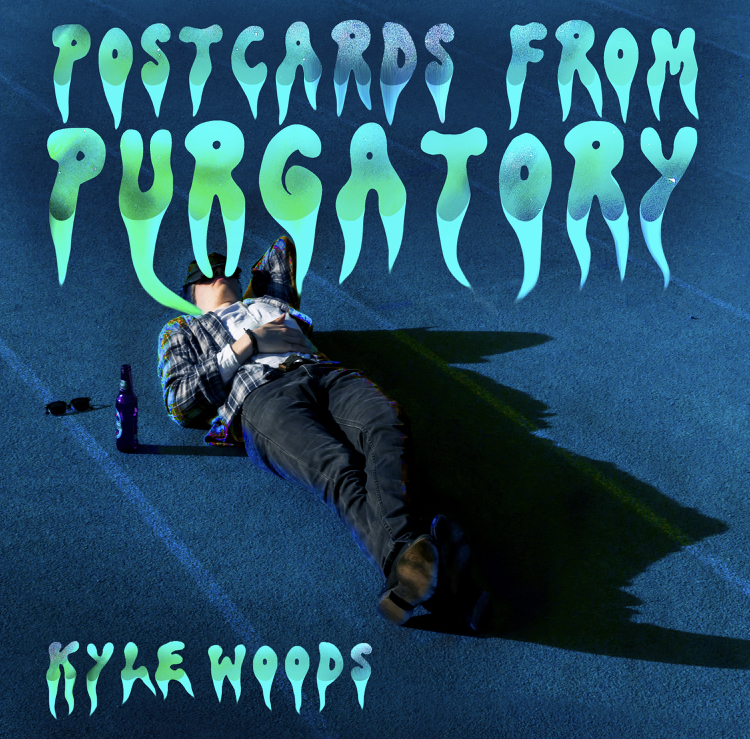

Postcards from Purgatory is the new album written, produced, and released by Kyle Woods over the course of the lockdown. He recorded the album “right here” in his bedroom, a feat that would not have been possible for many even fifteen years ago. Woods states that “most, if not all of it” has been a product of the internet, as well as the development of technology. From the production software of Logic and the release platform of Spotify, to the low-fi blend of genres and eras characteristic of modern music, the album is thoroughly rooted in its time.

Woods views the rise of the internet as a largely positive thing, especially for musicians. “I love the whole DIY approach to music which has been going on long before the digital age, but the internet has just opened up so many doors, and made it so much more accessible to people.” He speaks enthusiastically about accessibility and the democratic effect it has on the music industry, as “it limits you as much as you limit yourself.” The internet has provided seemingly boundless opportunities for creatives, yet when Woods speaks, the enormity of the commercial music industry is ever-present. “Because you can meet anyone anywhere, it should be this perfect opportunity. But something like 40,000 songs are uploaded to Spotify every day. It’s incredibly hard to cut through.” The democratisation of music has therefore led to a switch in focus for artists, as they must compete not just through established companies, but with masses of other individuals.

There is a clear tension when Woods speaks between being gifted a resource such as the internet, with its endless production technology, while simultaneously meeting more concrete barriers such as time and money. “That’s not to say that anyone can do it. Equipment is expensive, it took me years to save up and get all this stuff.” While some artists have gotten discovered simply by singing on YouTube or Vine, for many there remains the challenge of money. The industry has seen a rapid increase in accessibility in recent years, yet even the cost of equipment and the time needed to produce quality work are indisputable obstacles for artists set on releasing their first album. Woods admits that while recording an album was an ambition of his for years, the opportunity still seemed out of reach, which rings true for innumerable people in the arts.

“The industry has seen a rapid increase in accessibility in recent years, yet even the cost of equipment and the time needed to produce quality work are indisputable obstacles for artists set on releasing their first album.”

Suffice to say, the lockdown changed that. Woods finally found the chance to write and record a ten-song album, and released it in July. Despite it not being a new dream, and having used many of the musical resources he would have had regardless of the lockdown, he maintains that the experience certainly left its mark on the work. “In terms of that kind of stir-crazy tension of like when you’re in lockdown, that probably did add to the sort of feeling of the songs. If you’re tense, you can hear it in your voice, if someone’s kind of nervous, their throat is tighter, you can kind of hear it.” The space and time this music was created cannot be extracted from the album. And indeed, while Postcards from Purgatory is a boppy, dreamy assortment of songs, there remains a palpable nervous energy throughout.

A defining feature of lockdown was the constant anxiety surrounding productivity. Many wasted no time in announcing their goals online, and artists like Taylor Swift emerged in the summer with an album that went straight to number one. Yet the period drew attention to the toxicity of our obsession with productivity, and appearing to use time to the full. Woods admits to thorough procrastination at the beginning of lockdown, yet he is enduringly positive about the opportunities he gained from it. Having settled into a routine, he was given the chance to find a consistency he now deems necessary to create.

“You hear a lot about musicians who lock themselves in the studio, and maybe there is something to that. I think you can get into a rhythm, a creative rhythm. I think there’s something to everyday- working and making stuff gets you into a flow, and you get all of the garbage out of the way. Eventually you’re like, okay, I kind of like this.”

“Woods admits to thorough procrastination at the beginning of lockdown, yet he is enduringly positive about the opportunities he gained from it.”

Much like having a daily routine to find creative rhythm, Woods speaks about needing to create a musical foundation from which to spring from when actually writing the album. “Then you have a nice framework to be creative lyrically or melodically with vocals, you have a playground, a box to play in.” He claims to lean on the guitar for this, saying “it’s a weird comfort thing.” From there he increased the number of instruments and penned the lyrics. Yet he is also quick to remark that anything can spark the process and that the beginnings of new songs can be found anywhere. “Film would be a huge influence for me, the song Fear & Loathing on the album is kind of literature and film. I think everything influences song-writing, and I think if you’re not honest about that, you’re deceiving yourself.” He smiles wryly when he says this, but the smile quickly turns to an awkward grin at the next question.

“Film would be a huge influence for me, the song Fear & Loathing on the album is kind of literature and film.”

When asked if he listens to his own music, Woods seems embarrassed to admit to it. “Yes, recreationally, I think so. I know you shouldn’t say that.” However, he remains earnest about his reasons for doing so. “It’s trying to capture a particular moment that I experienced, I listen to it and relive that experience, and I can know exactly where I was and what it felt like. Also to try and improve on things… it’s not all reliving the past.” People seem happy for others to plug themselves online, but to interact causally with their own work seems to be a different matter. For someone to say they enjoy something they’ve made, continuously runs the risk of sounding pretentious. Woods acknowledges this with the same grin, as he says “I know people are like, ‘Oh, self indulgent much?’ But I made it for a reason.” He is somehow both apologetic and assured.

Woods remains mortified of others hearing his music around him however. “That’s almost a nightmare of mine.” He cringes at the thought of touring, as he admits that “performing live kind of terrifies me.” In the past, that would have been unthinkable for a musician that wanted to gain success, yet again the internet provides an alternative. Woods muses that virtual gigs would be more of an option for him, but smiles again when asked about live gigs. He will do them “if it comes to it.” His primary focus remains music-making itself, as well as the connection afforded by the sheer reach of the internet. “I value way more if someone contacts you and is like, this song reminds me of this, or makes me feel something I’ve never felt before, and that does it for me. That’s where your numbers are nothing, this is a person.” The removal of barriers between creator and consumer have opened up previously unthought of potential for connection.

“He cringes at the thought of touring, as he admits that ‘performing live kind of terrifies me.”

The freedom granted by the internet is a running theme with this album. But while artists are finding fame and success on online platforms, they still ultimately go on to sign with labels and do worldwide tours. In making this album, Woods has found a discord between the established norm and the changing landscape of the music industry. He is enduringly upbeat about the independent movement online, yet acknowledges that “record deals are still a big thing. For a lot of musicians that’s still the goal.” He speaks passionately about wanting to avoid a system that routinely takes advantage of people for “as long as possible”. When assessing the current landscape, he asserts that “artists I think now have the best opportunity to stay independent and not have to make a deal. I think that is a genuine career opportunity.” While still in the era of big labels, it is clear a dramatic shift must have taken place to even entertain this idea.

The notion of a traditional music-making career is also present in the album itself, despite the numerous liberties afforded to digital artists. Woods comments on the process of realising artistic freedom not only hypothetically but in practice. “I did have this set thing in my head, it’s ten songs, just keep working until you get ten that you like. In terms of editorial process, I’m not sure there was one.” He smiles and proclaims he would do it differently if given another chance, yet the product of the album speaks for itself. In terms of making art, there seems to be an unassailable merit in simply creating until you stop.

Yet the process of actually releasing music independently, without any external help, seems murky at best. Woods had taken a very relaxed approach to promotion until he started researching the industry. “I originally had that ‘drop in into the world, see what happens’ view, then I realised if you don’t do certain things, your music is going to essentially reach no one.” He put together a series of Facebook ads, performing snippets from some of his songs. “That made a weirdly huge difference.” If independence from restrictive labels is the underlying objective of the indie movement, then it seems artists still cannot remain independent from the entire system of music consumption. “The way it is these days with social media is you can’t reach people without spending a little money.” He takes a balanced view, but ultimately effuses that it is worth it. Reaching people proves the most rewarding end.

“The way it is these days with social media is you can’t reach people without spending a little money.”

Woods is enthusiastic about being a musician in starting in Ireland, where we are richly populated with emerging talent. “It’s so exciting to see these Irish artists getting a global stage and I’m just really excited to have the privilege and opportunity to play music, at least for now.” However, he is keen to express the work that is necessary to put in, alongside that strong sense of optimism. “If you want a career, which is essentially a business endeavor, you need to learn how streaming platforms work, and how music is distributed and promoted. It’s a rabbit hole of stuff, which I definitely got lost in. It’s like there’s this whole underbelly.”

Coming to terms with the more arduous elements of the industry was a surprising lesson learned from the release of the album. “There’s this weird shelf life that music has, and I realised that music is also kind of a product.” Early disillusionment here seems all the more difficult for artists to avoid when met with the more consumerist side of their work. When speaking of the differing attitudes, Woods demonstrates his adaptability. “It’s how you look at it, it’s an opportunity, or a challenge. But you just need to look at it the right way.” Woods’ eagerness is infectious; Postcards from Purgatory is an album that offers encouragement to creatives across the board, to take a leap into the unknown, and to trust themselves.