The moment I entered George Wallace’s exhibition in the National Gallery of Ireland, I knew I was in for a treat. His prints jump out, they say hello and they welcome you in, so you are now looking through the eyes of the artist himself. The show had been running from September 11 right up until December 13 (before further coronavirus restrictions, with a new final date to be decided) and returning for a second look has become a priority. One hour is simply not enough to view the lifespan of his works from the 1920s to 2009 which his family donated to the Gallery in 2016, now on display for the very first time. Over 60 pieces were donated, and there is no time more fitting to display them than on the centenary of his birth. Reflections on life is an exhibition representing Wallace’s artistic influences and his many life changing experiences. Wallace used what he saw in newspapers from his time at Trinity, where he studied philosophy in 1939, to create meaningful works of art. Most, if not all, are extremely graphic, at times humorous, but never stray from realism.

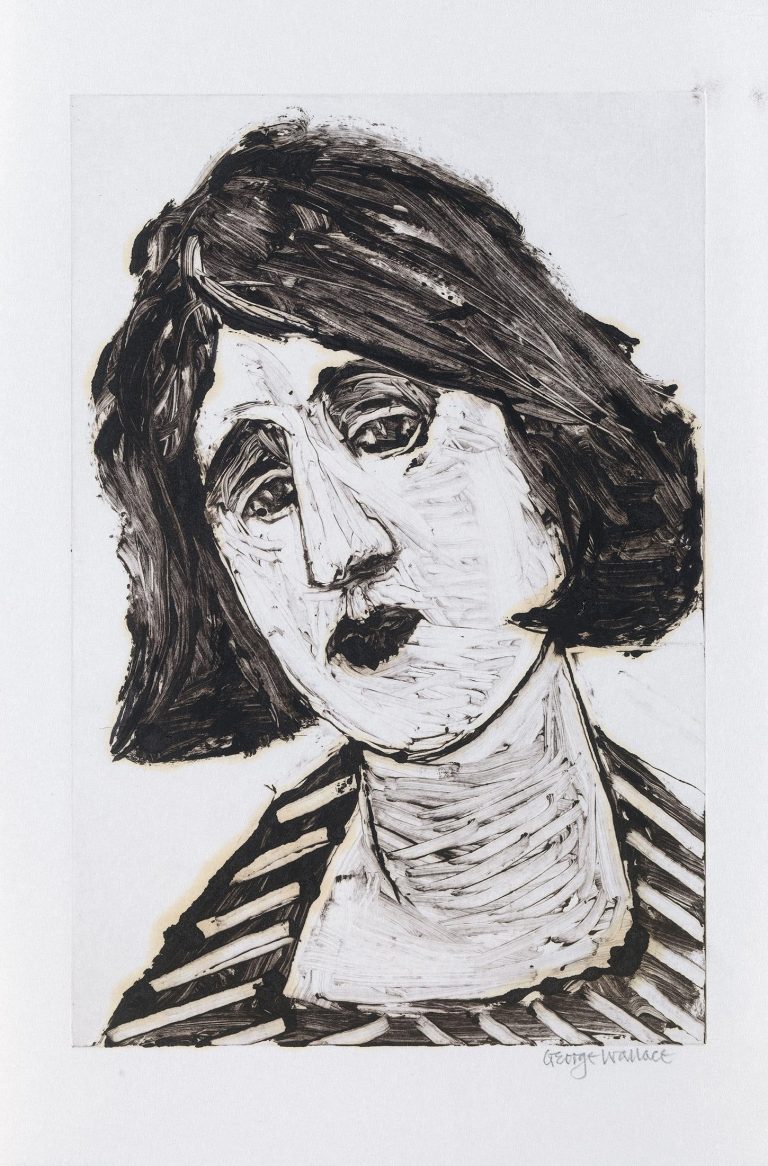

I began with the monoprint Young Woman in a Striped Dress. I was wooed by the richness of the medium and the evocative expressions difficult to create with white paper and ink alone. Wallace utilised what is called the “light field manner”, where his image was painted onto paper in ink and detail was worked into it using cardboard scrapers, giving this young woman in a striped dress dark sharp lines, while negative spaces are left white. The print itself is bold, dark and rich, but her expression is soft and sincere. Wallace also made his own printing inks, mixing oil paint with lamp oil or Kerosene.

I then moved thematically to his Summer Shadow etchings. I pondered how one person could bring so much life to a page. His series of 12 etchings in black and white juxtapose the navy background, and the series begins with a self-portrait of the Busy Artist. I examined the 12 insights as if holding a microscope to them — I felt bad for the people standing behind me cramming to see clearly. The television set acted as the focus of the collection. As the figures go through the simplicity of ordinary mundane life, the television set portrays a more glamorous and synthetic version of their daily routines. The etching technique was used alongside monoprints, aquatint, lithography, lift aquatint, deep etching, washes, watercolours, soft ground, and dry-point ink work. The television screen was an interesting theme, and, during the 1950s, acted as a parallel universe. The detail from the engravings revealed the emotions of anxiety, failure, and boredom felt within the realistic sense. The last print, Day of Reckoning, showed the TV sets being thrown in a pile like the rubbish they materialistically are, and concluded my favourite section.

Wallace’s humour emerged sporadically throughout the exhibition. He satirised society’s obsession with the television set, displaying them as a trusted companion, the way one might relate to today’s obsession with smartphones. His work was realistic, sometimes extremely serious but often had whimsical qualities that made them appealing and viewable. His humour revealed itself again with his series of mugshots conveying Canadian businessmen. I viewed Another Successful Banker from 1996 and then Big Businessman from 1992. His inspiration came from Canada’s national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, and kickstarted the satirical prints. The expressionless businessmen look out at the viewer and emanate, in Wallace’s own words, a sense of “self-involvement and alienation”, and to me, sheer entertainment.

The gallery chose a very spacious area for the wall hangings, offering peace and quiet in the print room. The pieces were grouped well, ordered in themes from when they were created. Heavy spotlights shone overhead made the pieces stand out even more against the navy and the labels displayed to the right-hand side gave enough details to inform its viewers of relevant information.

Similarly to the businessmen mugshots, the Unwelcome Guest II, made in 1996, caught my attention. A menacing image from afar, but upon closer examination, revealed a softer and sadder observation. An example of Wallace’s philosophical way of approaching his artwork, this piece draws attention to the fact that death will eventually overcome us all. In his mid-70s he too suffered the eventual conciseness of his own mortality and, with this piece, he lets us examine his thoughts. Most of his monoprints were printed on Japanese paper, which created a silkier surface for the ink to spread on and for a rich impression to be made of his figures.

No doubt religious imagery was a major theme in his work and in this exhibition. He took vivid imagery to the next level in Ecce Homo, a large evocative image of a beaten Jesus Christ. There is no sense of divinity or superiority in this portrait — just of blatant human suffering. Religious imagery was a common theme in western art since the 15th century, but Wallace’s depiction is convincingly compassionate. Ecce Homo, meaning “behold the man” in Latin, is placed upon Christ by Pontius Pilate, governor of the roman province at the time, before he handed Christ to be crucified. The raw image shows a crown of thorns over Christ’s head, a swollen lip, bruised eye, and dishevelled appearance. Wallace gives us a compelling image of cruelty and torture, yet one cannot look away. The engagement he created in his pieces, from figure inside to viewer on the outside, amazed me. He continued the theme in his pieces Christ Walking in the Garden and Death of Judas, which again are jarring to observe.

I was then brought to Pilate himself, created in 1956. Wallace certainly showed us his obsession with the famous faces of the Bible while imagining their feelings and emotions in the religious stories. But instead of portraying the holy and the mighty throughout history, he focused on the humanity and fragility of these biblical figures in order to present us with hidden insights. He also created statues of biblical figures from steel during the 1950s which are now mainly on display in Canadian universities.

As I walked towards the last room of the three-roomed exhibition, I was brought to his earlier works which are inspired by his Irish roots and early childhood. He moved to Bristol in his younger years to attend art college where he taught at the School of Art and Design at West of England College where he discovered St Austell, a landscape famous for its pits and fossils. Most of his earlier pieces are inspired by this naturalistic place and his pieces, such as Joined Forms, Dark Landscape, Fortifications, and Pit Workings demonstrated this tastefully. He experimented more with colour form to create various compositions of the same pieces, often displaying two different versions as seen in Clay Pits, created in 1955. The landscape of St Austell is his primary source for depiction and he looks at man made objects for inspiration. These were lovely to view in contrast with his previous images of figures. Most were simplified and flattened buildings. He wrote that these were vast scenes, “at times sinister but entrancingly varied”. From his theme of ordinary life and religious life, I was brought to a new theme of war and conflict.

While Wallace studied at Trinity College, he also saw in the Irish newspapers the last remnants of World War II. Like his biblical figures, he inflicts pain and suffering into his piece, Prisoner, created in 1955, and Burnt Man in 1961. To me, the most horrific of the series were Gagged Man, Weeping Woman, and Head of a Caged Man, images in which he appears to be trying to make these figures be seen and heard. In snippets throughout the room, he offered brief relief from the torment. In his Landscape, made in 1954, he painted a wild and uncontrolled watercolour vista.

Wallace had been exposed to war images in the news for most of his life which clearly affected his upbringing. Once he was in college, the Korean war was almost a memory and the Vietnam war was on the horizon — these events were keenly observed in his pieces. He created Man in Helmet and used red, blood coloured ink to depict him, attempting to portray the political futility taking place at the time. He was an artist to be admired — he told difficult stories throughout his time, often troublesome to digest.

Throughout his lifetime, Wallace witnessed an incredible array of events, some wonderful and some woeful. Through the stories he tells in his art, we are thrown back to the 1950s to events that should never be forgotten. Between June and August 1988, he produced over 100 monoprints that are a mixture of loss, hope, and a longing for better. His alarmingly honest self portrait was refreshing while also melancholy. Most of this exhibition displayed his deep empathy for humanity. He certainly used his art to comment on the state of the world around him, and his most powerful prints revolve around the feelings of grief, sorrow and pain caused by oppression, war and, sometimes, the mundane. He commented on Hogarth’s work which is very much like his own: “He thought of his prints and paintings as mirrors in which the people of the time might see themselves reflect…in their sometimes grim, sometimes humorous surfaces we may perhaps still find something of ourselves reflected back to us.”

The insight he has given us with this exhibition is a story told by himself to the people of events long past. He offers us something very rare. While the exhibition includes harrowing images of brutality, torture and hurt, one can only describe it as truly beautiful.