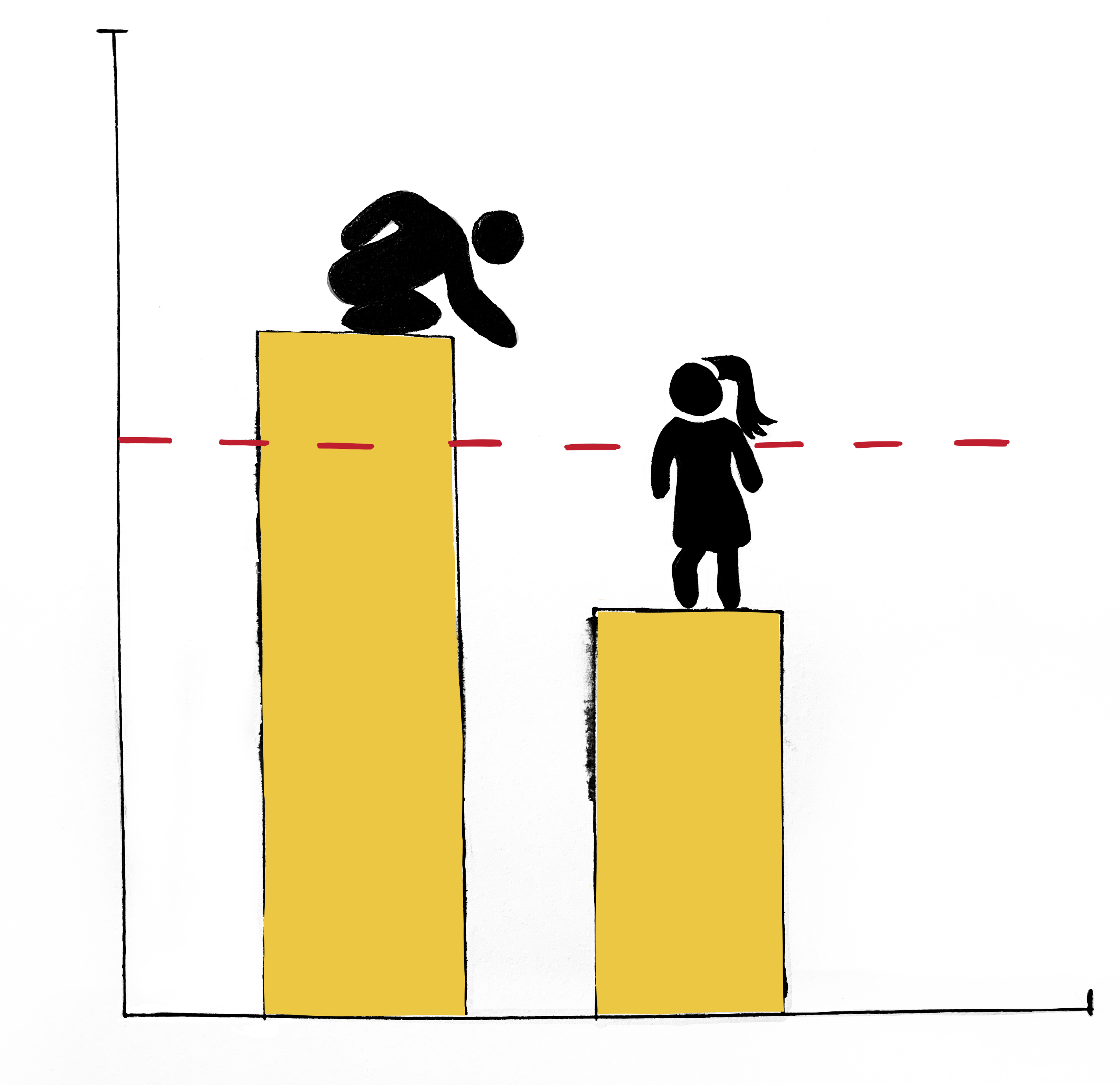

It’s no secret. Underrepresentation of women as workplace leaders remains a pressing problem. According to Deloitte, women hold only 16.9% of board seats globally. McKinsey (2019) further highlights the issue by reporting that females represent just 38% of first-level managers, despite constituting 48% of entry-level hires. To generate workplaces in which young men and women advance equally into leadership roles, we must first address the blatant gender disparity in ascending to the peak of the corporate ladder. We ought to figure out why we see so few females in top positions, despite most graduate employee pools being gender equal.

According to Dr. Stephen Murphy, Assistant Professor in Marketing at Trinity, “women’s under-representation in leadership positions is not due to lack of skill or ambition. Organisational research consistently highlights that historically and culturally entrenched notions about gender hierarchy are at play in reproducing systematic discrimination against women at work.”

“In the workplace, women are frequently cast as nurturers and caregivers, and therefore lumbered with the additional burden of emotional labour”

“In the workplace, women are frequently cast as nurturers and caregivers, and therefore lumbered with the additional burden of emotional labour, while their male counterparts reap the rewards of longstanding associations between the breadwinning role and masculinity”, Dr Murphy explained. “Promotion opportunities that evince the value of merit remain constrained by these ideological power dynamics and are maintained by those who stand to benefit from them.”

In the quest for top talent, companies are yearning for ways to enhance competition, particularly surrounding the underutilised female talent pool. To attract more women, many organisations are enacting gender-based affirmative action solutions. Of these, one of the most contentious is the gender quota, where companies allocate a definitive percentage of roles for female employees. A much-contested topic, it remains to be decided: how necessary are they in the battle towards workplace gender equality?

Laura Gilligan has experience working in organisation design with one of Ireland’s top consulting firms. Her postgrad in Human Rights and involvement in Women in Business events have afforded her a breadth of knowledge around the gender quota issue and she is fervently in favour of them.

“Gender quotas are the first step towards bringing diversity and inclusion into your organisation”

“Gender quotas are the first step towards bringing diversity and inclusion into your organisation”, Laura began. “They are a brilliant tool for ensuring representation and promoting gender equality. I truly believe ‘if you can’t see it you can’t be it’, and therefore we need ample female representation at the top if we want lower-level females to progress.”

Gender quotas are often lauded for the “trickle-down effect” they can catalyse. “By using quotas to drive women up the ladder, more female leaders are available to provide mentorship to younger women and help them progress”, Laura went on. “Males often get promoted because they have access to an abundance of male mentorship. An absence of women in leadership positions means there’s no one from whom younger women can get that gender perspective, and thus they don’t get as much empathetic support. Having more female leaders to guide other women will culminate in an expansion of females in senior positions, over time.”

Laura also touched on the critical mass element that comes to light with gender quotas. “Having a sole female director on the board is much less impactful than having a few”, she said. “By using quotas to ensure representation by multiple women, you avoid the single woman sticking out and make more of an impact, especially at lower levels of the organisation.”

One of the main arguments against gender quotas is their capacity to potentially deprive a more deserving person of a job, which Laura disagrees with. “I think that argument is flawed because there isn’t equal opportunity for getting there. There are systematic issues like the mentorship piece, for example, which make it harder for women to get to an interview or nomination stage even”, she said. When groupthink is so prevalent in organisations, gender quotas are necessary to ensure women get to the stage where they can be considered for a role.”

Laura recounted a point made at a Women’s Day Speech she attended on design. “A female guest speaker discussed her experience working in gamification. Because gaming is such a male-dominated industry, quotas had to be implemented as games weren’t taking the female mindset into account”, she said.

“Another example of this is car design. Seatbelts and airbags are more dangerous for women because they were designed through a male perspective”, she continued. “Genders process and navigate through situations differently. Therefore, it’s imperative to combine the spheres of thinking of both males and females to ensure optimal design. By neglecting the female perspective, tools can be designed in a flawed way, which can cause harm and cut off an entire consumer base.”

As a caveat, Laura added, “Quotas won’t work, however, if they’re employed only at the top level. If we don’t start from the bottom, the pipeline of high-quality candidates won’t exist, and this can cause scepticism around whether the woman who gets the job is actually worthy of it. Therefore, quotas must be implemented at all levels of the organisation to ensure there is a continuous channel for women to advance to the top.”

Trinity News also spoke to Gillian Talbot, HR manager at one of Ireland’s leading airlines, who presented the other side of the argument against gender quotas. “Quotas spark the problem of merit”, she explained. “Women want to get to high places on the back of their own hard work and skills rather than via a quota. They don’t want to be seen merely as a ‘token woman’ who is there to fulfil a legal requirement. It undermines someone and people respect them less knowing they got their job because of their gender. In a way this can in fact affect career progression.”

“She begins to question whether she really deserves to be there and this in turn may affect her work”

“Not only that, quotas exacerbate the problem of Imposter Syndrome among women- a worry that they’re not good enough for the job”, Ms. Tabot went on. “I believe gender quotas can make a woman doubt herself and hamper her confidence. She begins to question whether she really deserves to be there and this in turn may affect her work.”

Ms. Talbot also pointed out that quotas may spark frustration and irritation among men, which can lead to more workplace disputes and tensions: “I don’t think gender quotas can solely induce equal gender representation. Existing barriers for females, like having children, cannot be cleared up by gender quotas. If being in a leadership position requires working until 10pm every night, it’s just not attractive for mothers, and most will steer away from that kind of lifestyle”, she said.

So, in the battle for gender equality, will quotas really help matters? According to Dr Murphy, “the failure to reconfigure the gender composition of organisations based purely on merit, has meant that gender quotas are frequently proposed as a possible method of overcoming the systemic inequalities that hamper women’s progress at work.”

“When women are equally represented in the boardroom, notions about what it means to be a leader and how leaders should act will surely develop in kind”, he concluded. Whether quotas are the best means of achieving gender equality remains up for debate. But, one thing’s for sure, as Laura outlined, if they’re worth doing, they’re worth doing right.