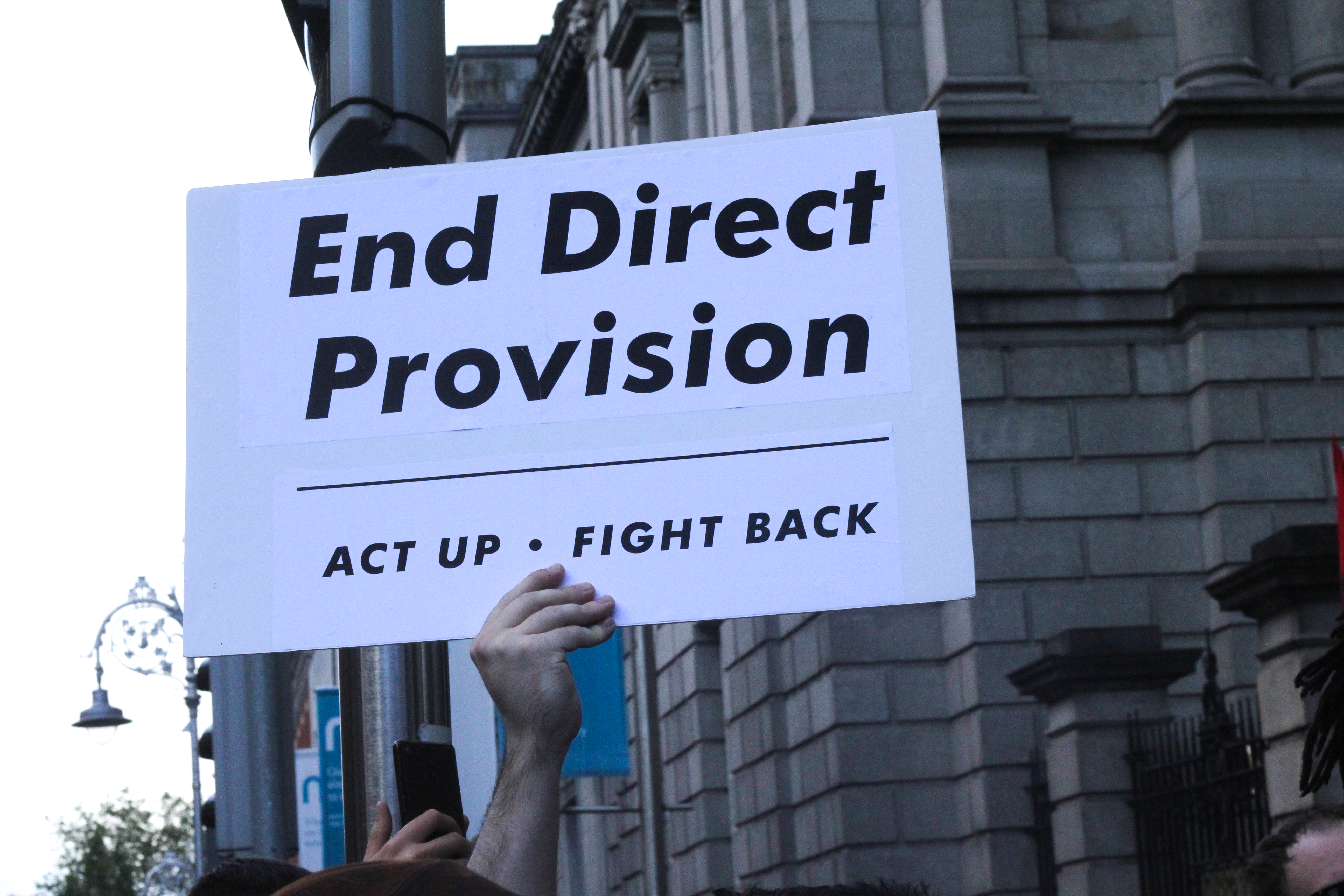

The much-awaited White Paper on Ending Direct Provision by Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth Roderic O’Gorman was published publicly at the end of last month. The government in Dublin has committed to developing the much-touted new and improved international protection accommodation system. The government hopes to successfully replace the current Direct Provision system for asylum seekers coming to Ireland. The new system, which is set to be phased in over the next four years and fully implemented by December 2024, is considered by the Government to be the new paragon for “integration and inclusion” here in Ireland. At a news conference, Minister O’Gorman said of the White Paper: “We are not looking to reform the system; we are looking to end it and bring about a new model of accommodation.”

However, broad concerns over the timeline of implementing this new system remain in play due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Many citizens and observers of Irish policy in the E.U. and abroad wonder aloud if the new system will take longer to implement than initially projected and planned in this document. When asked about concerns over the current timeframe of implementation, Minister O’Gorman replied, “I have always tried to be as honest as possible that a change of this magnitude cannot be delivered in an incredibly tight timeframe, but I believe the timeframe we have set out is ambitious.”

“The new system will also change how accommodation and support will be offered to people applying for International Protection.”

One of the most important aspects to come out of the publishing of the White Paper, especially for students in the Direct Provision program that are looking to study or are currently studying at third-level, is that these students who are part of the Direct Provision program will no longer have to pay (the much more expensive) international college fees. The new system will also change how accommodation and support will be offered to people applying for International Protection. From the beginning of their arrival here in Ireland, asylum seekers applying for International Protection will be able to access support across health, housing, education, language and employment, and will be offered accommodation for up to four months in one of the many new Reception and Integration Centres that the government intends to build. After four months, those still under Protection claims will be granted accommodation access across the greater Irish community, with their own-door or own-room accommodation. This represents a stark departure from the current housing in place under Direct Provision, which mainly includes shared dormitory-style rooms. International Protection applicants will subsequently be able to work and earn a wage after being here in Ireland for six months.

There is no doubt that the publishing of the White Paper indicates that the Irish government is moving in the right direction. Change was required. However, much work is still needed to ensure this new system adequately cares for and provides for asylum seekers in the Republic. The current direct provision accommodations have been described by the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland (MASI) as poor, overcrowded, and with rooms crammed to the brim in order to maximise profit for those providing a roof over Ireland’s most vulnerable heads. The United Nations has also called on Ireland to end Direct Provision. The current system has allowed Irish state-hired private contractors to earn over €1 bn in profit since Direct Provision began. The payoff is often made by cramming several people into single rooms; a scene which harkens back to the periods of urban poverty during industrialisation in the last century; a scene which Dickens himself would recognise. While the abject horrors of the current system, which the Irish Supreme court even determine as “unconstitutional,” will be coming to a necessary end, the proposed system does not allow asylum seekers to live independently without state supervision.

“While asylum seekers will no longer be housed in isolated detention centres, they will still have no autonomy over where they and their families will end up.”

Even under this ‘revised’ new system, asylum seekers will not be offered government support for their first four months here in Ireland should they choose not to live in a Reception and Integration Centre. These new arrivals will continue to have no say in what destination their community accommodation will be, being denied the language, religious and community support that many depend upon as they begin a life in a new land. One of the more well-known examples of the importance such community infrastructure can play in determining the success of new arrivals is that of the Irish — just ask anybody in early-20th century Boston or New York. While asylum seekers will no longer be housed in isolated detention centres, they will still have no autonomy over where they and their families will end up, and will have little say in how they start their lives off here in Ireland.

Most importantly, the changes proposed in the White Paper will not be on a statutory footing, making it incredibly difficult to hold the government accountable and leaving these asylum seekers with little to no legal protection. While the new proposed system makes long-overdue changes, it still fails to allow asylum seekers to make their own autonomous decisions, especially with regards to housing free from increased state supervision. Minister O’Gorman has a unique opportunity to improve an improved-upon, yet still flawed, policy to the benefit of Ireland’s newest arrivals and her citizens that already call this island home.