These are real, shocking incidences that happen to people every day. When such occurrences have happened to me, I have always felt horrified, upset, threatened, and deeply alienated from the rest of those around me. I do not go about my everyday business hyper aware of the fact that my skin is darker than most of the people of the people I am with, but in instances like these (and there are many of them) I feel distinctly different; a rather uncomfortable, but sadly inescapable feeling.

And that is why both of Brendan O’Neill’s recent articles (both prompted by his speech in The Phil’s debate ‘This House Believes in the Right to Offend’) in The Spectator and the Irish Independent respectively have made me very, very angry. In the first, he paints opposition guest speaker Asghar Bukhari of the Muslim Public Affairs Committee UK, as an ‘apologist’ of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, and in the latter he more broadly condemns students as overtly politically correct, championing against his belief in the right to offend.

I personally still haven’t made up my mind about whether or not people have the ‘right’ to offend, but having experienced racism, implicit and explicit throughout my life, I do know how damaging and painful offensive behaviour can be for those who are on the receiving end. This is something that Brendan O’Neill will never be able to experience, and thus cannot understand at a personal level, given his privileged position as a white man.

But instead of acknowledging these simple facts O’Neill continues to prattle on about how political correctness ‘infantilises’ those it is designed protect. I, as a woman of colour, don’t feel like I am being coddled when someone has the courtesy to refrain from calling me a ‘paki’ or calling people of my religious background ‘jihadists,’ ‘terrorists,’ and ‘brown scum.’ In fact, I actually quite like it when the difference in my skin colour or ethnic background isn’t mocked, or made out to be something I should be ashamed of. Even if I am being infantilised, as O’Neill claims I am when people are just polite, I’m ok with that, because developing the thicker skin he places so much importance on is certainly not worth the hurt, pain, and sickening estrangement I feel when someone offends me on the basis of my identity.

O’Neill has a penchant for terming the political correctness that we students have been engaging in as ‘censorship’ – a misguided application of the term, in my own, brown, female, opinion. People can and probably will continue to say whatever they want. What we’re trying to make people aware of is that sometimes things you say hurt people, and that it is far better for society to be aware of that.

And this is what Bukhari tried to explain to the audience at last Thursday’s Phil debate. O’Neill’s misleading account of his speech in his article on The Spectator portrays Bukhari as a defender of the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Bukhari, who has experienced Islamophobia and racism, delivered a speech that was an impassioned attempt to show that attacks like these happen for a reason, and that we will not be able to overcome the divides between the Islamic community and the West until we attempt to recognise and examine this reason.

I do not defend the horrific actions of those people, and I highly doubt it was Bukhari’s intention to condone those actions either. But what Bukhari, and I, and many others like us, can do is shed a light on the perspectives of those who are offended and show how damaging offensive actions can be. Not only to relations between groups, but also on an individual’s self-esteem and mental health. O’Neill and other white, cisgender males can’t ever truly understand the effects given that they will never be on the receiving end of racism or any other form of social oppression. On several occasions during O’Neill’s speech I attempted to offer him a point of information; I wanted to ask him, ‘Are you a Muslim? Are you a person of colour? Are you a woman?’

And sure, as O’Neill tried to tell me after the debate, not every member of a particular group experiences the kinds of prejudices we talk about, and Bukhari and I probably can’t and don’t represent the views of Muslims as a whole – but I don’t think we claim to. We are merely speaking out on issues that we find unjust and if others like us happen to agree then we are speaking out on their behalf also. What O’Neill can’t seem to comprehend is that, in actuality, a lot of people do feel similarly to us, and his inability to accept this is bewildering.

Unfortunately, people like Brendan O’Neill are allowed to voice their ludicrous opinions on issues which they have had no direct interaction with, and more problematic and frustrating than this is that they are applauded for it. In all honesty, I am sick of white men like O’Neill trying to tell me how I, as a woman of colour, experience everyday life. I am sick of people thinking warped logic like his makes sense, because it is too uncomfortable to accept the grievances that those on the margins have. I am sick of people shutting down those who experience and speak out about the struggles that come with certain aspects of identity and I am sick of the likes of O’Neill telling me that my anger is misplaced.

However, if O’Neill and others like him are going to propagate their misguided thoughts on the matter, then I am certainly free to remind everyone that there is another, far more legitimate side to this discussion, a side that comes from those who experience prejudice, a side that has time and time again been dismissed, but so badly needs to be listened to.

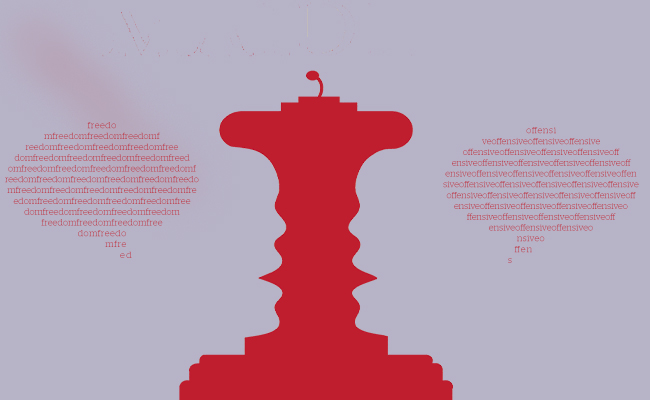

Illustration by Aisling Crabbe