Tommy Gavin

Deputy Editor

Apathy, indifference; the weariness that begs the question of whether it’s even worth the effort of paying attention, and ultimately concludes that it’s not. Apathy allows the voter an escape from the compromise of trying to pick the least-worst option, or having to wade through the endless cycles of spin-doctoring. It allows the elected to expect compliance on one hand, and to shift the blame onto those same apathetic voters for their own exclusion on the other. It is the oil that lubricates the engine of the modern democratic state. There is no middle ground on the apathy question, you either see it as reckless civic irresponsibility, or the rejection of naïve and idealistic posturing. Even in student union elections, addressing apathy about student politics is one of the most reliable talking points for candidates, because people who care want everyone else to care, and people who don’t care; don’t care.

Apathy is not exclusively an Irish phenomenon, but it is one the Irish seem to excel at. There is a perception about Ireland, especially in continental Europe, that since people here aren’t rioting in the streets, they’re basically happy enough with how things are going. This fails to recognise that the apathy even seems to extend to civil disobedience (and surely using the relative breakdown of social order as a scale for assessing approval ratings is more cynical than apathy could ever be).

But what if apathy is a logical response? What is there to be apathetic about?

The Culture of Executive Secrecy

There has always been a notorious and deeply ingrained culture of secrecy in Irish governments and public institutions since the foundation of the state. This can partially be traced back to the context in which the state was formed, of a bloody civil war between different sides of the independence movement, and extreme secrecy at a cabinet level was one of the consequences of the Martial Law regime enacted by the Dáil in November 1922. There was already a pre-established deference to the views of established leaders though, with intolerance and suspicion accompanying any deviation from those views. The Official Secrets Act in 1963 further entrenched those tendencies, banning the release of all official documents without the express permission of the Minister responsible, and carried a jail term of up to seven years for breaches on indictment. The first big break towards transparency came with the Freedom of Information Act in 1997, having been pledged by the so-called ‘Rainbow Coalition’ of Fine Gael and the Labour Party. The sponsoring minister, Eithne Fitzgerald said that it would “turn the culture of the official secrets act on its head,” as it gave citizens new legal rights to access official documents.

This cause for optimism was short lived, only six years after the introduction of the Act, the Fianna Fail government affected severe restrictions on it with the Freedom of Information (Amendment) Act of 2003. The amendment introduced an upfront fee for FOI requests, causing the number of requests made by journalists between 2003 and 2004 to drop by 83%. Fine Gael and the Labour party were both duly outraged, and promised to legislate to restore the Act to remove the restrictions. Enter the Freedom of Information Bill 2013, initiated by the current Fine Gael and Labour party government. It extends the definition of public bodies open to requests, but The Gardaí, NAMA, the Equality Tribunal, the Labour Relations Commission and the Labour Court will be only ‘partially included’ in the new system, and what ‘partially included’ actually means remains to be seen. Furthermore, not only does the bill retain upfront fees, but multiplies them where there are multiple questions in a single request. In November, when Public Expenditure Minister Brendan Howlin appeared before the Dáil subcommittee on public expenditure to discuss the Bill, he was questioned by Independent TD Stephen Donnelly about how much money the government expected to raise. When Howlin admitted that his department couldn’t provide an estimate, he added that it was his “principled position” that people be charged “in the current climate.” Ireland is one of three countries that charge upfront fees for FOI requests.

Censorship and the Lack of a Right to Free Speech

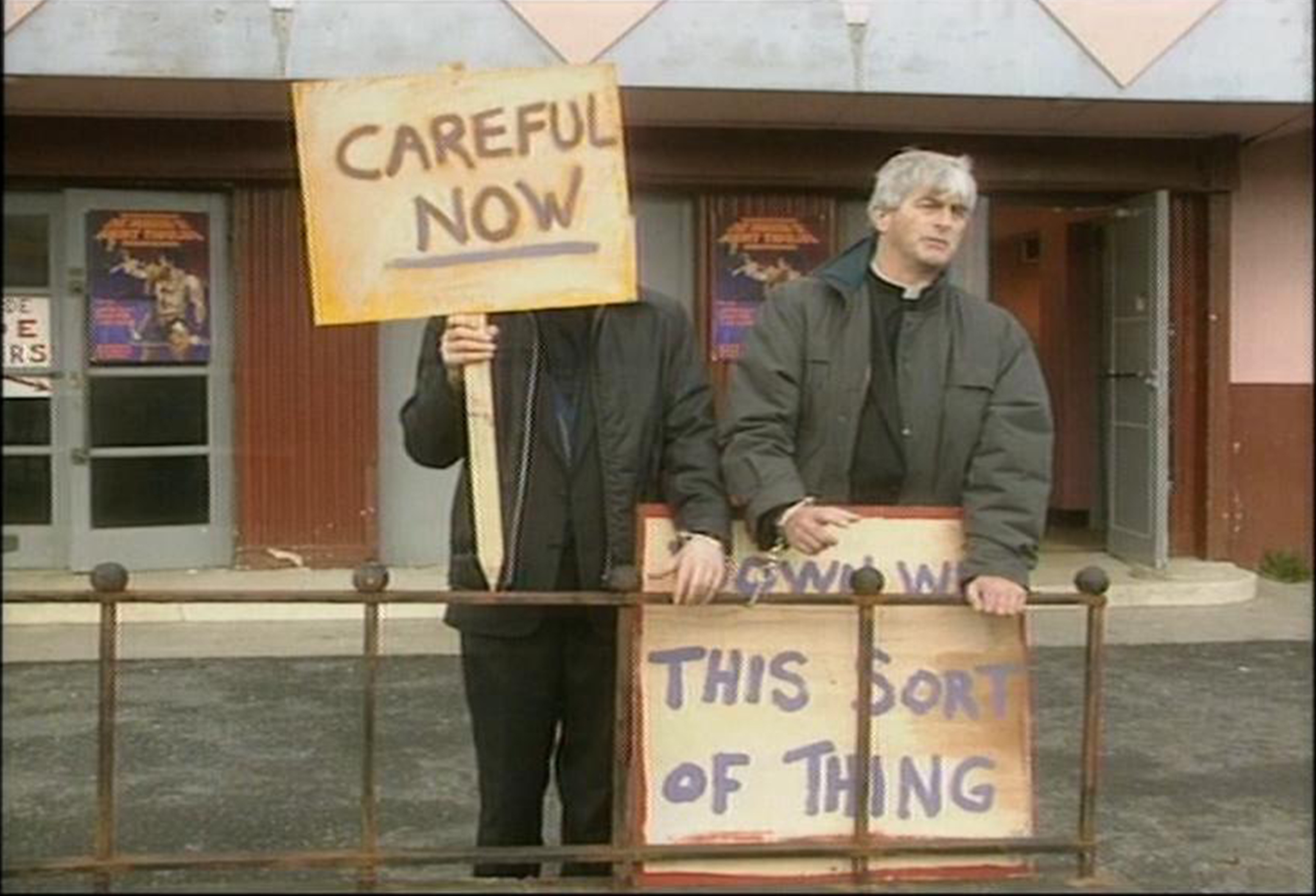

The culture of secrecy in government goes hand in hand with the lack of an established freedom of speech. One of the first acts on the statute books of the fledgling Irish state was the 1923 Censorship of Films Act which gave the power to an appointed censor to prohibit films thought to be “indecent, obscene or blasphemous.” The outbreak of World War II in 1939 lead to the creation of the Emergency Powers Act which empowered the government to censor all broadcasts and newspapers in the country, and set a troubling precedent. The outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the 1970s saw a return to that strict impulse of censorship through the infamous Section 31 of the 1960 Broadcasting Act. The law was implemented in 1971 and was used to prevent media in Ireland, principally Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) from broadcasting “any matter that could be calculated to promote the aims or activities of any organisation which engages in, promotes, encourages or advocates the attaining of particular objectives by violent means.” It meant that spokespersons for the Provisional and Official IRA could no longer appear on air. RTÉ journalist Kevin O’Kelly was jailed for contempt of court for having interviewed a member of the Provisional IRA, and refused to identify the person speaking on a tape seized from him by Gardaí. Subsequent amendments made it illegal to report on interviews with any member of Sinn Féin either. While there were similar laws in Britain, they were far less strict, and did not apply at election time. The Section 31 broadcasting ban lapsed in 1994, not having been renewed by the then Minister for Arts, Culture & the Gaeltacht Michael D. Higgins following the declaration of an indefinite ceasefire, but regardless of the politics of the Troubles, that the state would see fit to limit press freedoms for political reasons should be a harrowing thought.

The biggest barrier to free speech in Ireland at the moment is the extremely stringent defamation law. For one thing, blasphemy is still illegal under the Defamation Act of 2009, with a possible fine of up to ¤100,000. More practically though, it is generally very easy to take libel action if you can afford it, and generally very hard and very expensive to defend against. For that reason, the threat of legal action is often enough to shut down any debate, and it’s what prompted RTÉ to pay out ¤85,000 to John Waters, Breda O’Brien, David Quinn, and other members of the Iona Institute after Panti Bliss convincingly suggested that they are homophobic.

The station immediately apologised and settled the compensation out of fear that a lawsuit would expose them to risk of having to pay out hundreds of thousands of euro.

If we can accept then that there might be good reasons to be apathetic, then it might follow that it would be a more productive exercise to do something about the sources of apathy, rather than just complain about how apathetic Irish people are. But that would require doing something, and that wouldn’t be very apathetic.