Conor McGlynn

Deputy Comment Editor

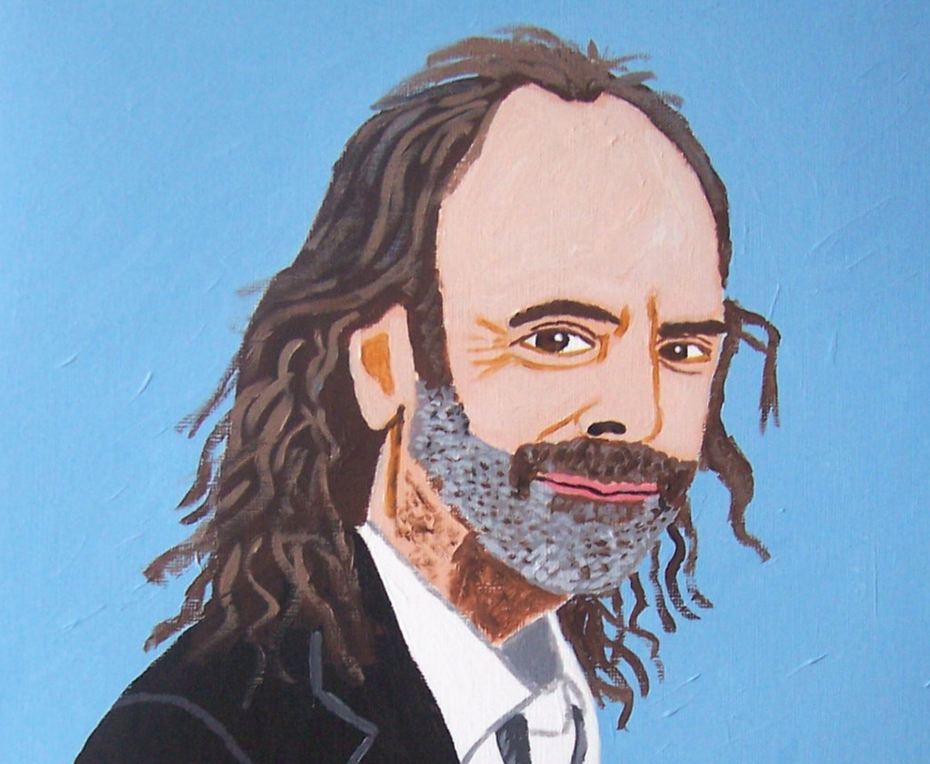

On a Friday at the end of March, it was announced that the columnist John Waters would stop contributing pieces to The Irish Times. Waters’ weekly column featured in the Friday paper since 1991, and dealt with a wide range of topics, from religion and politics to music and literature. His columns have not appeared for the last couple of months, the stated reason being that he was “on leave”; but on Friday it was confirmed that he had left the paper. The reason for his departure is presumed to be the controversy from the fall-out of the RTÉ homophobia affair. Waters and a number of other journalists were accused of homophobia, live on RTÉ’s Saturday Night Show, by Rory O’Neill, a drag artist known as Panti Bliss. A legal dispute followed, resulting in RTÉ issuing an apology and making payments to the defamed parties.

This whole affair has already generated a huge amount of comment and discussion in the media, and I will not address it very much here. Regardless of one’s feelings on the matter, however, it should be acknowledged that Waters’ departure is injurious to the Irish broadsheet press. Waters was a discordant voice in the increasingly one-way discourse of the Irish media. He gave voice to a viewpoint that is now often marginalised in public debate. In short, he was willing to challenge the consensus view.

Waters has often been attacked in the media for his views. He propagates opinions that are unpopular amongst what has been termed the “chattering classes”. He represents a broadly socially conservative outlook, informed by his Catholicism, about which he often writes. He is opposed to gay marriage and abortion. However, his defending of unpopular positions has also led him to champion causes and groups which are neglected by the political system, such as his fighting for the rights of single fathers. Many commentators, not least of all some at his former paper, will be glad to see Waters go. He does not share many of their “liberal” views. His opinions and writings have been censured as harmful and damaging, and as inappropriate for public broadcast.

“Regardless of one’s feelings on the matter, however, it should be acknowledged that Waters’ departure is injurious to the Irish broadsheet press. Waters was a discordant voice in the increasingly one-way discourse of the Irish media. He gave voice to a viewpoint that is now often marginalised in public debate. In short, he was willing to challenge the consensus view.”

Not all viewpoints and opinions should be shared, or should be allowed to be shared. Rounding up a lynch mob or calling for attacks on ethnic or social groups should not be permitted in any circumstances. Further, while some views may be tolerated they should not be legitimised or given a platform by public or prestigious institutions. University debating societies, for example, should not provide a forum for fascists and racists for the amusement of their members. However, this should not be interpreted as an excuse to exclude any and all who deviate from the consensus view.

The problem is, however, that there is no fine dividing line between these different brackets. There is no convenient demarcation between who should and who should not have a voice in public discourse. We cannot draw a distinct boundary between fascism and incitement to hatred, or between the dangerous and the merely unpopular. Over the past few months, arguments have been made that Waters, and those who share his views, should not have a place in the public discourse, and, further, these views should not be tolerated at all in society. According to certain commentators, in The Irish Times and elsewhere, if a person does not share their liberal views then they should be silenced altogether.

These attitudes are far more dangerous than anything John Waters has to say. Most people are critical of the power and influence the Catholic Church had in Ireland in the mid-20th century. However, often they misascribe the problems of such institutional hegemony to being somehow intrinsic to the Church itself. This is too simplistic a picture. The danger, both then and now, is in having an unassailable consensus; a dominant viewpoint against which it is impossible to go without being ostracised by the community. We may not agree with all of what John Waters writes or broadcasts. However, to think we should is to misunderstand the purpose and role of the media in an open society. The media should not act as echo chamber for prevailing opinion. It should not reinforce confirmation bias for any one ideology. It should instead strive to give as complete a picture as possible of the range of divergent viewpoints in our society. Columnists and commentators should reflect a wide variety of opinions and views. Not all viewpoints will get a voice on the national stage. However, deliberately to exclude contrarian viewpoints is not only bad journalism – it is also bad citizenship.

The closed society is one in which dissenting viewpoints are not tolerated. There is little point in having dethroned Catholicism from its central place in Irish culture if we are going to replace it with a self-appointed consortium of liberal high-priests, gatekeepers for what views are right and proper. In the 1960s, the Catholic Church in Ireland prevented guests who it felt would be morally destructive from appearing on RTÉ’s Late Late Show. Having freed ourselves from one form of censorship and suppression, we should not be so eager to jump into the constraints of another.

This article originally appeared in print on April 3.