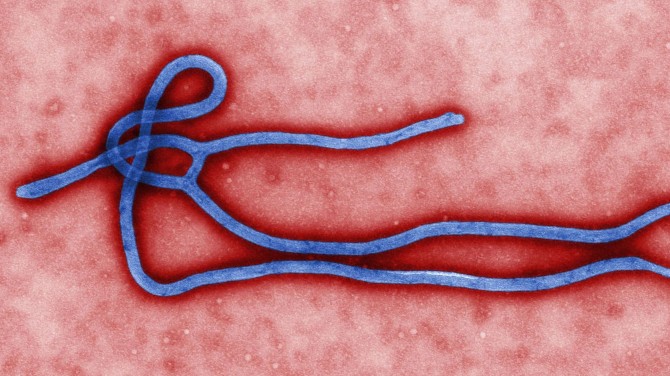

What is Ebola?

EVD is caused by the virus Ebola, the sole member of its species Zaire ebolavirus and the most dangerous of the five viruses in the genus Ebolavirus. It has an extremely high case-fatality rate of 83% on average, meaning that 83% of the people who contract the disease will not survive. Thankfully due to advances in modern medicine, better sanitation and a faster response rate the fatality rate for the 2014 outbreak has fallen to 52%. The symptoms of Ebola are very similar to those of Malaria and Influenza, and it is spread by coming into contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person. The average time it takes for symptoms to appear after contracting the infection (known as an incubation period) is eight to 10 days and symptoms usually appear flu-like in early stages but soon progress into vomiting, diarrhoea and impaired blood clotting. If an infected person does not recover, death due to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) will occur between seven and 16 days after the first symptoms, usually on days eight or nine of infection.

Current situation

Although the 2014 outbreak began in Guinea, it soon spread to surrounding African countries and reports began to flood in to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Fears that the virus would spread to other continents have been running high in the past number of weeks, with one particular incident involving a doctor returning to the United States causing widespread panic. However there are no current suspected or confirmed cases of EVD in the United States or Ireland. There are numerous reasons why the outbreak has been so severe in the African continent. Many of the areas where infection has been reported do not have any running water of soap to help limit the extent of transmission. Other factors also aid the transmission of Ebola virus, especially certain death customs such as ritually washing the body of the deceased. To limit the spread of EVD to other continents the CDC have issued several Level 3 ‘Red Alert’ Warnings which limit nonessential travel to locations including Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. Quarantine procedures are also currently being practiced in most countries around the globe.

There has been a lot of sensationalised news surrounding the outbreak in recent weeks, particularly one piece citing a scientific paper claiming that it is possible for Ebola to be transmitted via the air. Although claims of an airborne Ebola virus caused alarm amongst most news readers, they are completely false. In the study on which the paper was based, a pen of piglets with Ebola was housed in the same room as an unaffected group of Macaque monkeys. Even though the pigs had no physical contact with the monkeys, the Macaques contracted Ebola. However the actual reason that this happened was due to mucous and water particles which the pigs produced and shed/spat, which carried the virus through the air. This does NOT constitute airborne capabilities and it was concluded that physical contact with infected bodily fluids is necessary for Ebola virus transmission.

Progress

The 2014 outbreak of Ebola has greatly increased research efforts to enhance our understanding of its pathogenicity and also to find a cure. Monkeys infected with EVD were given a novel vaccine by leading pharma company Glaxosmithkline and up to five weeks after vaccination they are showing no signs of infection. These findings, which were published in the popular journal Nature Medicine, come two days after the World Health Organisation released a statement that preventative treatments could be available to medical aid workers in West Africa as early as October. Scientists are hoping to begin human trials with the new monkey-tested vaccine shortly. Phase 1 trials are going to be carried out in the Jenner Institute in Oxford, while the National Institute of Health will be running parallel phase 1 human trials in the United States.

An experimental drug called ZMapp has been reported as having ‘cured’ two health workers of EVD in recent weeks. This compound is being developed by Mapp Biopharmaceuticals in California and was administered after a blood transfusion from a survivor of EVD was given to Kent Brantly of the Samaritan’s Purse humanitarian organisation, nine days after he fell ill with EVD himself. Nancy Writebol, one of Brantly’s co-workers was also treated in the same way. Writebol and Brantly were released from hospital on August 21st, cleared of any infectious risk. However, it is undetermined when human clinical trials will be carried out, as Mapp Biopharmaceuticals have released a statement saying their supplies of the drug are currently exhausted.

Should you worry?

So at this stage you may be wondering is it time for Irish people to start worrying about Ebola? Short answer: no. Seasonal outbreaks of Ebola have been reported since the virus’ discovery and there have never been any confirmed cases anywhere in Ireland. The chances of the disease reaching our shores are very slim, as every single passenger boarding planes in West Africa is being checked for any symptoms by the World Health Organisation. There is also no direct transport route from West Africa to Ireland, so an infected individual would have to go unnoticed through several checkpoints before reaching us. Not to mention, our healthcare system is quite advanced compared to that of Sierra Leone’s and the possibility of EVD coming this far and taking hold is very low. Speaking to Pat Kenny on Newstalk earlier this month, Dr Darina O’Flanagan of Ireland’s Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC) said: “We’ve been preparing for the possibility for a long time. The risk is very low, but because it’s a very dangerous pathogen we’re ready.”

UPDATE: 03/10/2014 19:31; There is now one confirmed case of Ebola Virus Disease in the United States. The patient, and the others that he came into contact with, are all being treated for EBV in a quarantined hospital ward.