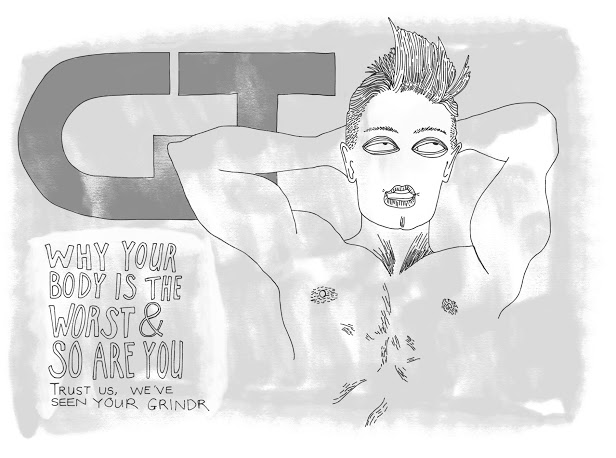

When someone realises they are queer, self‐loathing is a common initial reaction. Often, this manifests itself as hatred of one’s body due to a failure to experience exclusively heterosexual desire. The coming‐out process is often imagined as the antithesis to this, whereby queerness is eventually celebrated and a once deviant sexuality is reclaimed as natural and empowering. This journey is frequently aided by the discovery of queer media (such as magazines, vlogs and films) which reveal an exciting counterculture and cause one’s self‐loathing to ebb. The problem is that gay lifestyle magazines, such as Gay Times, Out and Attitude, which can be crucial in affirming a positive queer identity, simultaneously perpetuate new forms of oppression which teach queer men new ways to hate their bodies.

It starts with the covers. Each of these magazines emblazon their glossy fronts and website homepages with half‐naked (often straight) male celebrities, displaying their chiselled physiques. In June, Harry Potter star Matthew Lewis appeared on the front cover of Attitude. EastEnders’ Jonny Labey featured for Gay Times in August. It continues with the content. Out invites its online readers to “Watch Nicholas Hoult in various stages of undress”. Attitude contributes to the world of journalism by encouraging its readers to relive the “sexiest moments” of celebrities such as Jamie Dornan, Michael Fassbender and David Gandy. These are just a few examples, but it’s easy to spot a trend: the glorification of white, muscular, conventionally attractive and generally straight men.

It’s tempting to disregard this content and imagery as cheap, harmless eroticism. We should be wary of doing so for three reasons. Firstly, this content is being produced during an epidemic of eating disorders in the queer community. 42% of men who struggle with eating disorders identify as gay or bisexual. Queer men are three times more likely to develop anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa than straight men. By solely glorifying muscular, hyper‐masculine bodies, these publications embellish a story which says that small, thin and plus‐sized men are unattractive, because the corollary of worshipping one body‐shape is the shaming of all others.

Researchers have previously disregarded the notion that queer culture is to blame for the elevated rates of eating disorders within the community. In a study carried out by Columbia University in 2007, queer men who did not self‐describe as being “affiliated” with the queer community (and thus presumably with queer media) displayed equal rates of eating‐disorders as queer men who did. However, this ignores that one doesn’t have to view oneself as being heavily involved with the queer community to be exposed to the content of these magazines, given that they are easily accessible online, and market themselves as being mainstream, apolitical and casual magazines for the average Joe, gay man. It seems glaringly obvious that when many queer men consume this media, they learn to be uncomfortable with their apparently imperfect bodies. Undoubtedly, gay lifestyle magazines are not the sole cause of the high rates of eating disorders among queer men. However, it’s hard to imagine that promoting such rigid beauty standards does not impact negatively on maintaining a healthy body image. Claiming to empower queer men, while furthering harmful narratives around body image in a community where this is already a lethal problem is grotesque, yet it is an action of which these magazines are guilty.

Secondly, the content of these magazines further racism and transphobia in a community already embroiled in a storm of white supremacy and trans* erasure. There were no men of colour in the top ten of Attitude’s “Hot 100 Men of 2015”. White men are consistently sexually idolised in these magazines, while it’s difficult to find any appraisal of the physical beauty of men of colour. These magazines shouldn’t claim to represent the queer community when they systematically erase queer men of colour. In doing so, they prop up racist beliefs that white queer men are superior to men of colour, while telling queer men of colour that they are undesirable because they aren’t featured in these magazines. In a similar vein, trans* men are ciswashed. They are rarely discussed in the same terms as cis men; it is never acknowledged that trans* men are attractive. These magazines don’t feature trans* men on their front covers and rarely discuss their issues, lives or stories.

Thirdly, when straight men are applauded for being attractive by a queer publication (as happened when over half of the top ten of Attitude’s ‘Hot 100 Men of 2015’ were straight), it tells queer men that heterosexuality is valuable and to be admired. This heightens the difficulty queer men can have in accepting and being proud of their sexuality in a world which already stigmatises queerness. Sure, these magazines also depict queer men as being attractive, but when society is programmed to believe heterosexuality is correct and superior, any communication by a queer organisation that heterosexuality is desirable is extremely damaging for queer men because they lose a space in which they could previously affirm their sexuality. This is particularly true for effeminate queer men. On one level, they are otherised by a heterosexist society for being queer. On another, they are told by the queer community that they are lesser because they don’t fit the attractive, “straight acting” mould. These magazines contribute to many queer men resenting their manners of speech, movement and dress.

Gay Times, Out and Attitude need to stop displaying half‐naked, white men on their covers. They need to stop objectifying the male form and glorifying masculinity. If they genuinely want to work for the queer community, they should use their platform to talk about real issues, such as the extreme violence faced by trans* people and to give a voice to queer and trans* women. I’m sceptical that these magazines have any interest in doing that. We therefore need to stop purchasing these publications, to stop clicking on their articles and to stop following their social media presence. A decline in their popularity would at the very least create more space for queer media that represents the most people possible, and that doesn’t perpetuate harrowing mental illnesses. Coming out as queer should be about forging a new and empowering identity. These magazines stunt that liberation, and therefore have no place in our community.

Illustration: Naoise Dolan