Health and Wellbeing

“It was only later that I realised all of these moments of insomnia, heart palpitations, shortness of breath and paranoia were panic attacks”

Statistics about mental health always seemed so abstract to me. The leading cause of death for men between the ages of 15 and 34 in Ireland is suicide. Until I was 19 I hadn’t known anyone personally who had taken their own life. Depression, anxiety or mental illness had never crossed my mind. It was not until I was sat in a church at a funeral of a schoolmate that I realised I was one of the young men struggling with their mental health.

I had spent a large portion of my time in secondary school as a competitive athlete. As a swimmer I spent most mornings and a lot of weekends in pools either racing or training. It’s easy to get wound up or flustered as a competitive swimmer. Swimmers spend large portions of competition weekends sitting in humid, stuffy pools waiting for their next event. Such idleness is a breeding ground for nervousness. It was always a point of pride of mine that I never suffered from being nervous. My coach once told me that he admired my “have-a-go” attitude. He liked that I was not afraid to race anyone. The fact that I hung onto that little compliment would show you how few and far between they were. This confidence that I carried with me made it harder for me to accept that I suffered from anxiety.

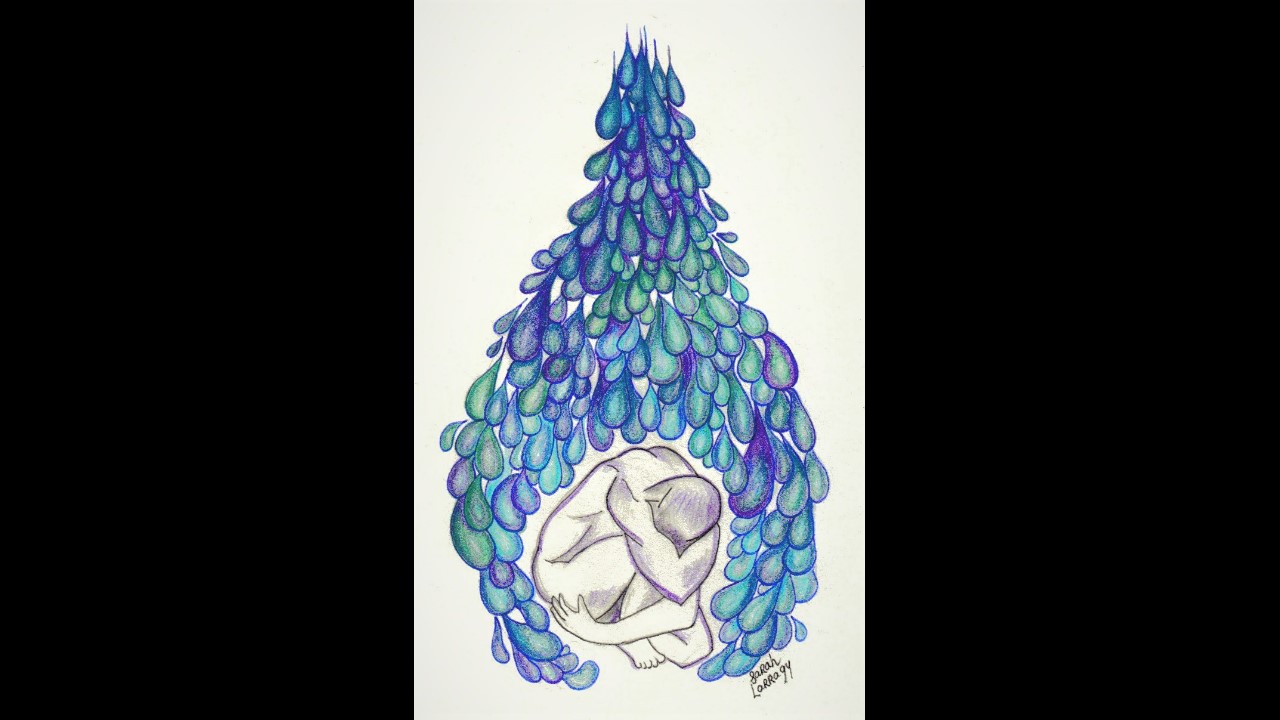

Everyone has a degree of anxiety within them. I liken it to a water tank in a house. Everyone has a water tank in their home and you don’t really pay it much attention to either until it’s a problem. When I swam and trained, the tank would be at a constant level. The anxiety would flow out when I trained and the tank rarely if ever overflowed.

When I graduated I had a rough idea of what I wanted to do. My plan was to save a little money, apply for a masters programme and work during the year. By June 2016, three weeks before the deadline of applications, my anxiety had reached such a pitch that I could not bring myself to apply.

Anxiety manifests itself in different ways for everyone. For me even the simplest tasks became a monumental challenge. Answering texts or emails was (and sometimes still can be) excruciating. The most imprisoning aspect is that you know what you should do. The right option is there in front of you and you recognise it as such. The problem is that you cannot bring yourself to do it.

I would find it hard to sleep. I would lie in bed, playing scenarios over in my head. As an athlete, and now as a coach, repeating scenarios and analysing them is part of the job. But the situation for me had changed. I was playing them back in my head and cringing. It is hard to describe this phenomenon. For me, Adventure Time was most succinct in its metaphor, “ I just thought about my anxieties and it was like my mind hand touching a hot memory stove”.

“Anxiety manifests itself in different ways for everyone. For me even the simplest tasks became a monumental challenge. Answering texts or emails was (and sometimes still can be) excruciating”

I would regularly get heart palpitations, sweaty palms and feel hot all over my head. Someone would address me or ask me a question and I would go into a mental fugue. It made social situations nigh on impossible. It would breed anxiety in my mind. Every person who laughed or looked at me, in my mind at least, was talking about me. Every person who walked towards me or made eye contact with me was about to confront me about something. Every time my phone buzzed I presumed it was bad news and would be afraid to look at the notification. It was only later that I realised all of these moments of insomnia, heart palpitations, shortness of breath and paranoia were panic attacks.

I remember the moment my anxiety overflowed publicly. I had been feeling increasingly anxious for a number of weeks. My relationship with my parents had also become rather strained. My mother asked me if I had applied to the masters programme. When I replied that I had not, a shouting match erupted in my parent’s kitchen. Having not really cried for a long time in my life, I ended up crying a number of times that summer (including when Robbie Brady scored against Italy in June, but that wasn’t anxiety-related). At the moment in the kitchen, the anxiety water tank had come crashing through the roof leaving everyone drenched and covered in plaster.

Eventually my mother and my incredibly patient girlfriend pushed me to see a therapist. I was incredibly sceptical and immeasurably nervous. The office, located on a busy street, had a brass plaque with “Psychotherapy Services” blazoned across it. My biggest fear was that someone I knew would see me push that button and an awkward conversation would ensue. I was even more sceptical of the therapist himself. I had an uninformed, but nonetheless strongly held, conviction that therapists were charlatans. A friend of mine with experience of psychotherapy told me that the worst thing that could happen would be that I would decide it wasn’t working for me and try someone or something else. This ended up not to be the case.

It didn’t cure me. There was no curing to be done. The proverbial water tank was being restored and I was learning how to prevent it overflowing and leaving brown spots all over my mental ceiling. As a goal-orientated person (and a minor control freak), my therapist challenged me to drive the therapy sessions. Much like the fantastic coach I was lucky to have earlier in my life, he equipped me with the skill set to manage my anxiety. The right choices, which I had always known but was unable to choose, opened up in front of me.

The one thing that I found once I opened up to my friends was that nearly all young men go through something like this. The problem was that none of them think to do anything about it. When I opened up to a particular group of friends that I was suffering from anxiety and that I was taking steps to manage it, everybody’s response was the same, ”I’m glad you’re getting help”. I suppose the moral of the story isn’t that it’s alright not to be okay; I don’t think there is a moral.

“Statistics about mental health always seemed so abstract to me. The leading cause of death for men between the ages of 15 and 34 in Ireland is suicide. Until I was 19 I hadn’t known anyone personally who had taken their own life”

The one message I wish to get across is that if you read this, and particularly if you are a young man and see pieces of yourself in my story, go to speak to somebody. I wish I had gone to the Student Counselling Service while I had the chance. It would have better equipped me to deal with the anxiety that overwhelmed me when I left. Even with the mental plumbing skill-set I have acquired, every so often I sense a leak or people in my life see the brown spots on the ceiling. Yet since opening up, I can deal with these far better.

Some people, especially young men, like to think they are so unique that the things that they are going through happen just to them and that nobody would understand. I was one of those men. The truth is that every home has a water tank and if it comes crashing down on top of your bed one evening, nobody would judge you for it. In fact, you’d probably find that friends and neighbours would help you out in your time of need. Everyone suffers with anxiety in some way, at some time. If your anxiety ever overwhelms you, it’s not a reflection on you, sometimes, like your tank collapsing in on you, it just happens. Nobody would judge you for it.