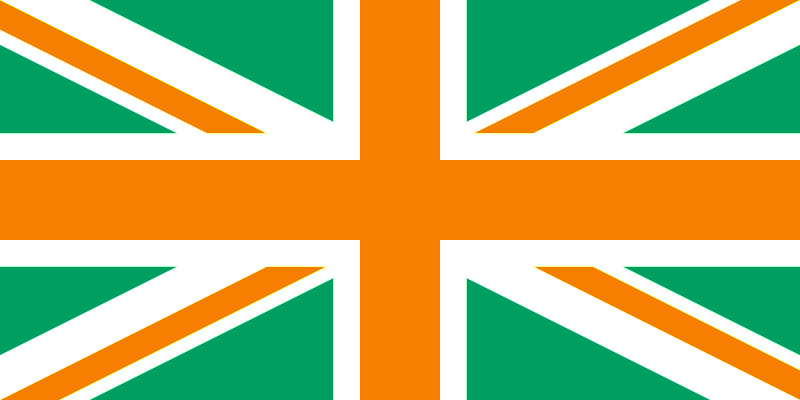

The question of national identity and its importance in sport has become ever more prevalent in recent years. As the barriers between countries are slowly broken down and dual citizenship becomes more common, this was bound to become a major issue in international sport. It is not unusual today for many to feel that they are citizens of more than one nation; the 2016 census found that 530,000 people living in Ireland have dual-citizenship. In a sporting context, complications arise when young protégés must decide for whom they will ply their trade on the world stage. Stars such as Bundee Aki, Lionel Messi, and Mo Farah have all faced this moral dilemma, which in recent times has become about a lot more than personal allegiances.

“In a sporting context, complications arise when young protégés must decide for whom they will ply their trade on the world stage.”

Much has been made in recent weeks of Declan Rice, a professional footballer playing for West Ham United as a holding midfielder. Rice was born in London but has Irish grandparents, making him eligible to turn out for either nation. He has come up through the youth teams for Ireland and has made three senior appearances. They have all come in international friendlies however, so is still able to switch allegiance if he wishes.

When Rice was approached by the England setup in August, he was omitted from the squad to face Wales by manager Martin O’Neill, who claimed that Rice was deliberating about his international future. As soon as this became publicly known, Rice faced huge backlash from the likes of Kevin Kilbane and other Irish footballing personalities who believed that Rice was a “traitor” and shouldn’t play for the Boys in Green again.

One of the big stories of this summer’s World Cup was Germany’s surprise exit from the competition at the group stage. While there were most likely many factors at play regarding their poor form, it can’t be denied that the controversy surrounding Mesut Özil and İlkay Gündoğan had a key role. The two stars, who both play in the Premier League for Arsenal and Manchester City respectively, have Turkish roots. Özil is third-generation Turkish-German, while Gündoğan was born to Turkish parents.

In May, both players were photographed with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, with signed jerseys from their respective clubs at a charity event in London. In a message written on his Manchester City shirt, Gündoğan addressed Erdoğan as “my president.” The photo incited outrage in Germany and attracted criticism from public figures and politicians alike. Both players were booed for their appearance in Germany’s pre-World Cup friendly against Austria and were blamed for Germany’s poor form at the tournament with Özil claiming he had received death threats.

On July 22, Özil posted series of messages on social media in order to clarify the meaning of the photo and address the criticism he had faced. In the lengthy post he stated that the photo was simply him “respecting the highest office of my family’s country”, that it was not meant as a political statement, and that his conversation with the president had revolved only around football. He also commented on the fact that many media outlets in Germany were using the story to push right-wing propaganda, singling out his Turkish background.

Özil later retired from the German national team, citing racism and disrespect within the German football association, the DFB, and later detailing that the core issue was his interactions with its president Reinhard Grindel. Many of Özil’s teammates criticised the manner of his retirement including Real Madrid star Toni Kroos, who stated that Özil’s claims of racism within the association are “nonsense”.

The French team, who won the World Cup, displayed brilliant talent throughout their ranks, but much has been made of the fact that a large proportion of their team were either born in various African countries or were born to African parents. With players like Samuel Umtiti of Cameroon and Steve Mandanda of Congo playing key roles in their success, some people have questioned the legitimacy of France claiming the World Cup as their own.

This conflict of national identity is not an issue exclusive to football. At the 2016 European Cross-Country Championships, two Kenyan-born athletes won gold and silver respectively representing Turkey. This event soon came under criticism from many athletics pundits including Sonia O’Sullivan, and has led to the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) attempting to take measures to tighten up restrictions on athletes switching national allegiance.

There is also a darker side to this story, according to research at Loughborough University in England. Their findings revealed that sporting agents in the African content have taken a leaf out of the book of human traffickers and smugglers that dominate the Mediterranean coast. They demand huge fees in advance for athletes to have the opportunity to compete in Europe: an issue that is compounded by corruption present in some sporting associations in the area.

A sizeable proportion of sports fans feel that representing one’s country in sport is a tremendous honour and that being selected is a privilege, one which you can’t just return or exchange for a different one. The more modern viewpoint however is that this attitude is a relic of times gone by: a by-product of 20th century right-wing nationalism. Sport has often been used by right-wing establishments to increase patriotic fervour within a country, to instil a feeling of nationalist pride amongst the people of a nation. Italy’s appearance at the 1938 World Cup is an extreme example of governments using their representative teams to further their political motives.

“A sizeable proportion of sports fans feel that representing one’s country in sport is a tremendous honour; one which you can’t just return and exchange for a different one.”

Today, it serves more as a means of conciliation between nations, of building bridges and improving relations. Given the fact that players representing teams other than their place of birth has become more commonplace, it seems that the idea of national identity is less relevant in modern sport. In the cases of Rice and Özil, we can see the issue come to the fore again, but on the whole it’s much less controversial. The Irish were all too happy to get behind Bundee Aki when he decided to represent Ireland even though he was born in New Zealand, and that perhaps is the crucial point.

“Once the whistle blows and the game kicks off, all resentment will be washed away; all that will matter is how he plays.”

The notion of national pride is rarely factored in anymore. Should Rice choose to don the green jersey again, the tides will change. Despite the heated debate and all the controversy, once the whistle blows and the game kicks off, resentment is washed away and all that will matter then is how he plays.