Accent

And few things are as bound up with our sense of identity as our accent. It shapes who we are, how people react to us, how we interact with every single person we meet. But if you think about it, making a hard and fast distinction between one group of people and another group of people, or even between one individual and another, on the basis of marginal differences in the noises we make with a hole in our face – well, it’s a bit stupid. Stupid as it is, it still plays a huge role in marking ourselves as one thing or another, and in a world which has become globalised, multicultural and generally “plural” – to the point that we are starting to realise that traditional concepts such as “nationality” don’t necessarily hold – identification based on accent is almost a throwback to a bygone era. For example, no sane person would deny another’s right to claim a given nationality as their own based on the colour of their skin, yet there is a sense that we can do this (and get away with it)when it comes to accents.

It’s about accent, about ownership, about supremacy over those “closest” to you.

The point of all this is that, in the sporting arena, accent tends to divide one group of fans from another (unless, of course, you are a Man Utd fan and you have any accent other than that customarily heard around Moss Side). If you were alive in the seventies or eighties and had little enough care for your immediate wellbeing as to go from London to Yorkshire to watch Millwall take on Leeds, and then went a step further in the attempt to realise your death wish by opening your mouth and revealing a London accent, you might find yourself slightly less towards the ALIVE end of the spectrum by the end of the day.

But all this changes during a local derby. Because during a local derby both sets of fans do the same sounds with their face-holes: accentual differences fade away, meaning that often the only way to tell two sets of fans apart is by the slightly less subtle method of making it clear that the opposing manager’s mother is a less than stand-up woman – a sentiment usually expressed in slightly different terms from these – or, otherwise, by simply cheating and taking into account the colour of their shirt. You might expect, logically, that in such a homogeneous pool (at least in terms of accent) fans might forget their differences and some sort of happy-clappy love-in might begin. Of course not. It almost seems that, without accent as a source of conflict, in a derby fans feel an impulse to compensate and assert their difference in even stronger terms.

Tribal warfare

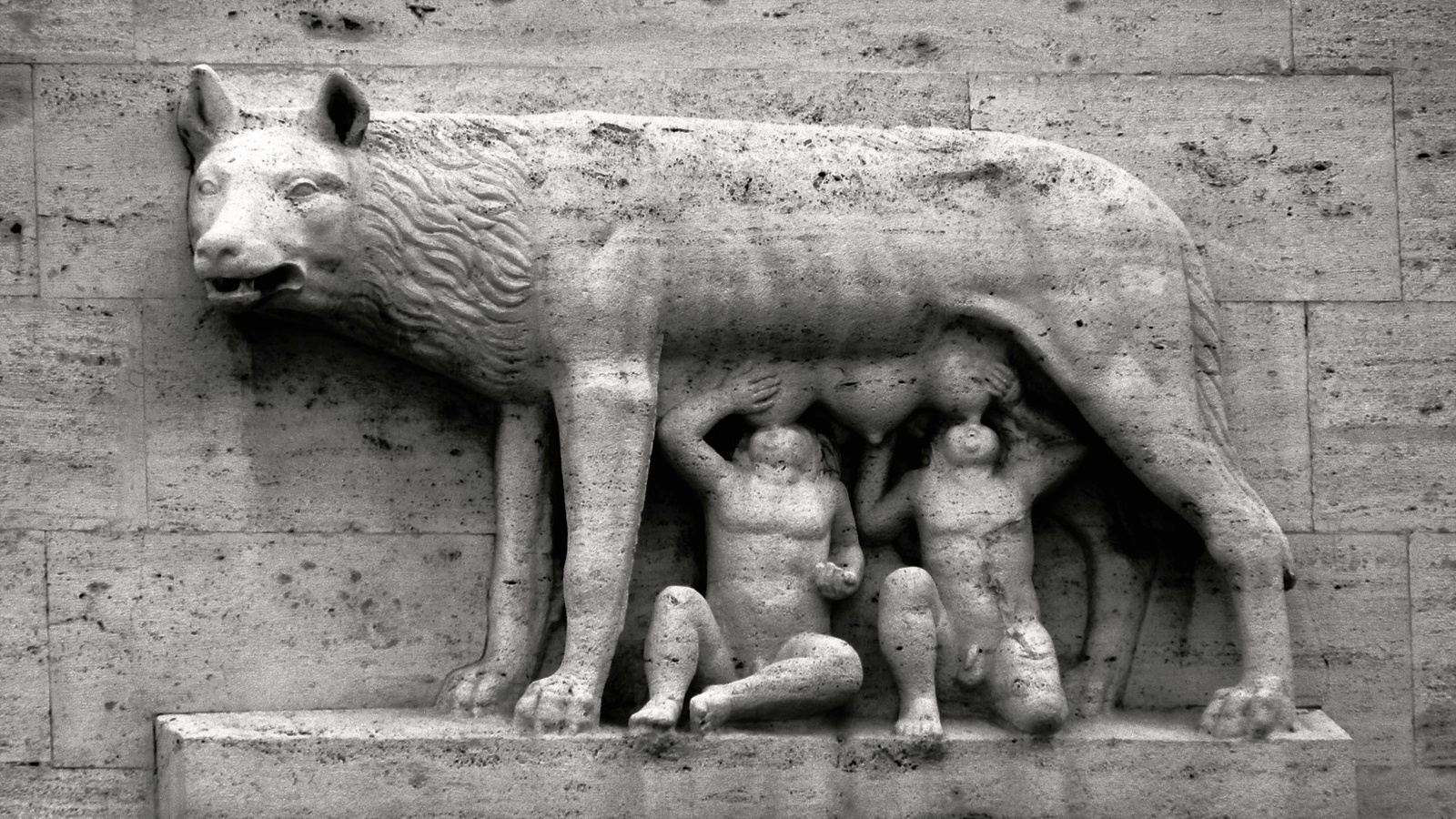

The aural homogeneity which causes friend and foe to coalesce, merging together as one unified voice, means that visuals take centre stage, in exactly the same way as they would have hundreds, if not thousands of years ago. This tribal warfare works now as it always did: entering the field of battle (the modern football stadium) wearing your side’s colours (today, this means an overpriced replica shirt), and with war-paint smeared across each cheek (even if it’s now cheap face paint you bought down the shops before the match). The parallels are so great that some even confuse the symbolic warfare of the footballing arena for the real, blood and guts warfare which it replaces. Bringing concealed weapons into the ground, they are unable to resist the temptation of the pseudo-violence on the pitch, allowing it instead to overflow into the stands in the form of real violence.

It’s about ownership. The local derby may be a battle for bragging rights, particularly when two sets of fans see each other every day – in school, in work, passing by each other on the street – but it is first and foremost about territorial rights, and in this sense it is a concept which almost transcends time: it is part of human nature, a constant which seems equally relevant to our prehistoric nature and the most recent social developments being realised all around us. The fear of immigration drummed up by a new wave of little-better-than-fascist political movements which have popped up all over Europe is a perfect example: it taps into the tribal, almost animalistic, base instinct which short-circuits rationality, overriding a thousand of years of painstaking social progress which had seemed to be leading us towards a more pluralist, enlightened place and replacing it with: THIS PLACE IS OURS, NOT YOURS.

This is why the local derby plays such an important role in modern sport. It’s about accent, about ownership, about supremacy over those “closest” to you. It’s a historical re-enactment, seen countless times before in as many different contexts, and it is where the most fundamental tensions of human society manifest themselves. But don’t worry, it only happens twice a season.