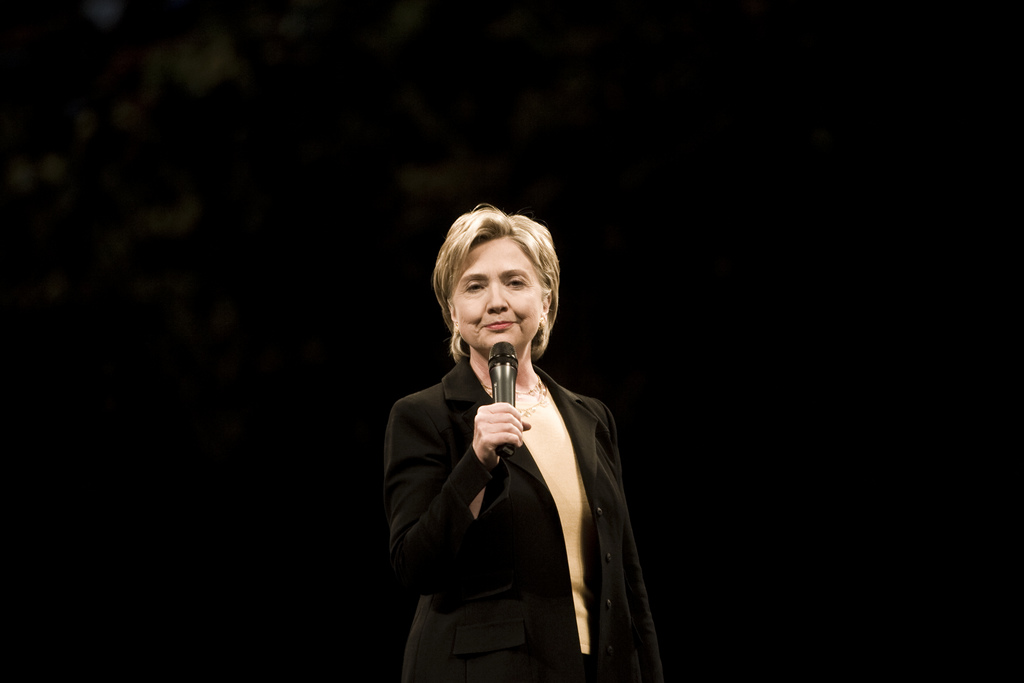

Writing in the Harvard Educational Review on behalf of the Children’s Defense Fund in 1973, the year of its foundation, Hillary Rodham encapsulates here the perennial concerns of child rights advocates seeking to address the legal conception of children’s status. Her focus was on American public policy and case law. My intention is not to analyse the thoughts of the then future first lady and US secretary of state. The concluding words to her article do, however, serve as the focal point of this article:‘Without an increase in community involvement, the best drafted laws and most eloquent judicial opinions will merely recycle past disappointments.’

It is an apparently universal phenomenon that adults experience children as representatives of both their mortality and their immortality. A focus on children’s rights serves in particular to address the bottom-up question, how do children experience adults? A lot has changed since Thomas Hobbes’ mid-seventeenth century publication of ‘Leviathan’. One of the most influential philosophical treatises in human history, in it he proclaimed that ‘Over natural fools, children or madmen there is no law’.

Today, thanks largely to the almost universal ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1989) the concept of international children’s rights has undeniably come of age. This Convention is the most widely-ratified human rights treaty in history and the first globally-binding treaty protecting children’s civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. Ireland is one of 193 states to have ratified it.

Given my own passion as a doctoral candidate focussed on an expository theory of children’s human rights, I should offer a brief introduction to my field. Theorizing about the nature and substance of rights is controversial terrain across which many competing contingencies stake their claims. Within the realm of children’s rights there are two central philosophical debates that wrestle with each other.

The first of these is the ‘choice’, ‘will’ or ‘agency’ theory of rights. Based on the assumption that the individual in possession of rights will have a choice as to when and whether to exercise them, this theory suggests that rights flow from rationality, autonomy and power. Given children will not always be in a position to exercise choice competently, can they accurately be described as bearers of rights (as self-determining moral agents) in the first place? Competency is an essential strand of this theoretical outlook so what of physically and mentally disabled adults? Should they also be denied the status of rights holder?

The theory avoids this conclusion by conceding there may be ‘correlative’ duties on parents/adults and institutions to provide a remedy for those lacking the required competence to make their own choices. However, this compromise clearly fails to address the underpinning right of children to be cared for, nurtured and protected in the first place. Furthermore, what of those parents and institutions failing in their duties to protect? The choice theory’s presumption that such duties correlate seamlessly is problematic, particularly when we know from the considerable literature on child abuse, it is frequently the case that the greatest threat to a child’s integrity comes from the parents and other close family members and friends.

The ‘interest’ theory of rights, meanwhile, seeks to address the limitations of the choice theory by placing emphasis on whether children have interests that require protection, rather than on the right holder’s capacity to claim or assert rights. Accordingly, society’s recognition of the need to provide children with care and protection is a sufficiently stable foundation upon which to construct an edifice of children’s rights. Some of these identified interests would then be translated into moral rights and a proportion of moral rights would in turn be granted the status of legal rights.

Clearly it is possible to establish a hierarchy of interests, based on merit and importance, that society in general is likely to agree with. However, an inevitable uncertainty lies in deciding which of these interests should be elevated to the status of rights, why and according to what criteria. Despite these difficulties the interest theory’s admirable aim is to ensure access to legal rights regardless of the level of competence a child can demonstrate in making choices.

Law and its agents, including Constitutional Law and our Supreme Court Justices (not to mention legislation and our elected representatives) cannot and should not be attributed with magical powers.

The law does not establish relationships; it merely recognises them and provides an opportunity for them to develop. Contrary to negative notions propagated at every level of society and particularly by the media (in every manifestation) human rights are not, in any pessimistic sense at least, selfish claims. At one level they can have meaning only in terms of a collectivity, as signifiers of relationships of equality. Children’s rights, on this basis, are fully equivalent to the rights of adults. Autonomy amounts to very little if a human being is isolated. Autonomy is therefore made possible by relationships and circles of responsibility towards one another, not through separation and the antagonistic pursuit of individualistic needs and wants.

Professor Michael Freeman has recently declared at a conference held in Dublin (Making Children Visible, 6 July 2012), children’s rights need a noisy (non-violent, of course) revolution to offset how children are conceived and treated as social constructs rather than individuals deserving of respect and dignity. Let us all get involved and play our part in the discussions needed to make this happen.

Children as humanity’s hope for a better future are not merely ‘the living messages we send to a time we will not see’ as expressed by Neil Postman, the American author, media theorist and cultural critic. Rather, we as children – past, present and future – are fully fledged human beings as well as human becomings entitled to the conditions necessary for a good life.

As we await publication of the Fine Gael – Labour government wording and date for a referendum aimed at strengthening the rights – the protection and place – of children in Irish society, a human-oriented and democratic spirit is needed more than ever. Society will humanise itself not just through its continued extolling of freedom, equality, or rationality. It also needs to open-heartedly embrace others in their full and resplendent difference and diversity, to celebrate, with cultural chutzpah, ‘otherness’, so as to render society more humanly inclusive.

Gandhi considered the best test of a civilised society to be the way in which it treats its weakest and most vulnerable members. In these times of potentially cataclysmic material and symbolic constitutional change in Ireland, let us also take to heart the words of Nelson Mandela, echoing those of Gandhi: ‘There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children’.

So how will Irish children experience adults in the coming months of debate? Every child, every human being has the right to respect. It has not been my intention here to offer specific suggestions but merely to urge Irish communities to engage. Failing to encourage and embrace the equal social participation of children in this historic process of change is to reject an opportunity to contribute fruitfully to a society in which the views, experiences and dignity of all ages are respected.

On this note, it is appropriate that the last word should go to another first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, whose oft-quoted sentiments, first expressed in 1958, are as relevant today as they have ever been: ‘Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works […] Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.’