In October, the government announced that it would not be opposing the Child Sex Offenders (Information and Monitoring) Bill 2012 proposed by Independent TD Denis Naughten. The Bill calls for “an Act to provide for the establishment of a scheme to allow the parents or guardians of a child or vulnerable adult to make an enquiry to the Garda Síochána for the purpose of ascertaining whether a person with whom their child is in contact has been convicted of a sexual offence or is otherwise likely to pose a serious danger to children.”

The Minister for Justice Alan Shatter is also going to publish the General Scheme of a Sexual Offences Bill in the coming weeks, which will address a broad range of issues relating to sexual offences. Shatter said that this draft legislation will provide a statutory basis for disclosures to members of the public. The discussion around child abuse and how we think it best to combat it in Ireland today is reflected in both proposals. As a society and a state, we are concerned with repeat offenders and minimising the threat posed by those who we already know are a threat. In his speech made on behalf of Alan Shatter, concerning Naughten’s proposed Bill, Brian Hayes TD highlighted some of the key points of the situation of child abuse in Ireland. Most sexual crimes committed against children are committed by people who they already know and trust. Hayes also said that the most up to date studies show that the recidivism rate (repeated relapse into criminal behaviour) for sex offenders is actually lower than that for the average offender. Less than 5% of those released committed a further sexual offence within the three year study period.

“Putting structures in place to help paedophiles deal with their issues before it manifests itself in child abuse is the first step.”

If neither “stranger danger” nor repeat offenders are the most serious issue in the sexual abuse of children, how can the state manage the problem? The approach of Naughten’s Bill points the focus onto both these issues, neither of which appear to be the crux of the matter. Speaking on the recent case in Athlone (where two girls, both under the age of ten, were raped by a thirty year old man visiting the area), Fiona Neary, executive director of Rape Crisis Network Ireland, told The Irish Times that public access to a sex-offenders register would not have prevented the crime, given the random nature of the attack. Hayes said that “Recent events have shown that we have to be ever mindful of the dangers posed to our children and must explore all avenues that will enhance their safety.” So what are the other avenues?

The World Health Organisation, a body to which Ireland fully subscribes to as a member of the UN, is responsible for publishing the International Classification of Disease (ICD), the worldwide standard diagnostic tool for “epidemiology, health management and clinical purposes.” The reason behind the production of international classifications is so there is a “consensual, meaningful and useful framework which governments, providers and consumers can use as a common language” when discussing health.

According to the ICD Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, paedophilia is a sexual preference disorder. The disorder is characterised by “a persistent or a predominant preference for sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children.” Another feature for the disorder is that the individual “acts on the urges.” Mental health has never been more prevalent in both the public and the state’s eye than it is in Ireland today. As a state and as a society, we are supposedly tearing down the stigma that has long been attached to the issue. The subject is, as we can see here in College, the darling of the public consciousness. Nearly everything it seems has been discussed in terms of mental health.

If you are depressed you can contact Aware. If you are suicidal you can call 1life. I don’t mean to be flippant. These are fantastic services that improve the fabric of society we live in. They should exist and they do. But not all mental health issues are being addressed. Paedophilia, the disorder as defined by the WHO, is not and cannot be illegal, in the same way that being depressed or suicidal is not and cannot be illegal. You cannot make it illegal for someone to think something after all. Child abuse, however, is and, of course, should be illegal.

However when the WHO definition of paedophilia includes that a sufferers “acts on the urges”, immediately, the issue becomes greyer. But it is obviously an incredibly complicated issue and the problem is that we are ignoring the nuances. As a result, we are harming countless children and, to use the medical term for someone suffering from a particular medical disorder, paedophiles. There is a huge problem with definitions when it comes to the subject of paedophilia and child abuse. As stated, paedophilia is a recognised medical condition by the authorities by whom we abide in the area of health. Once a term has been defined as a medical condition then it must not be used to describe something nefarious that it can be related to but is not synonymous with.

The term paedophile does not imply the abuse of children or that any crime has been committed. In Ireland, unfortunately, the term paedophile is synonymous with child abuser and, if you read The Sun, “monster”. This has crippled any debate on the subject in mental health terms.

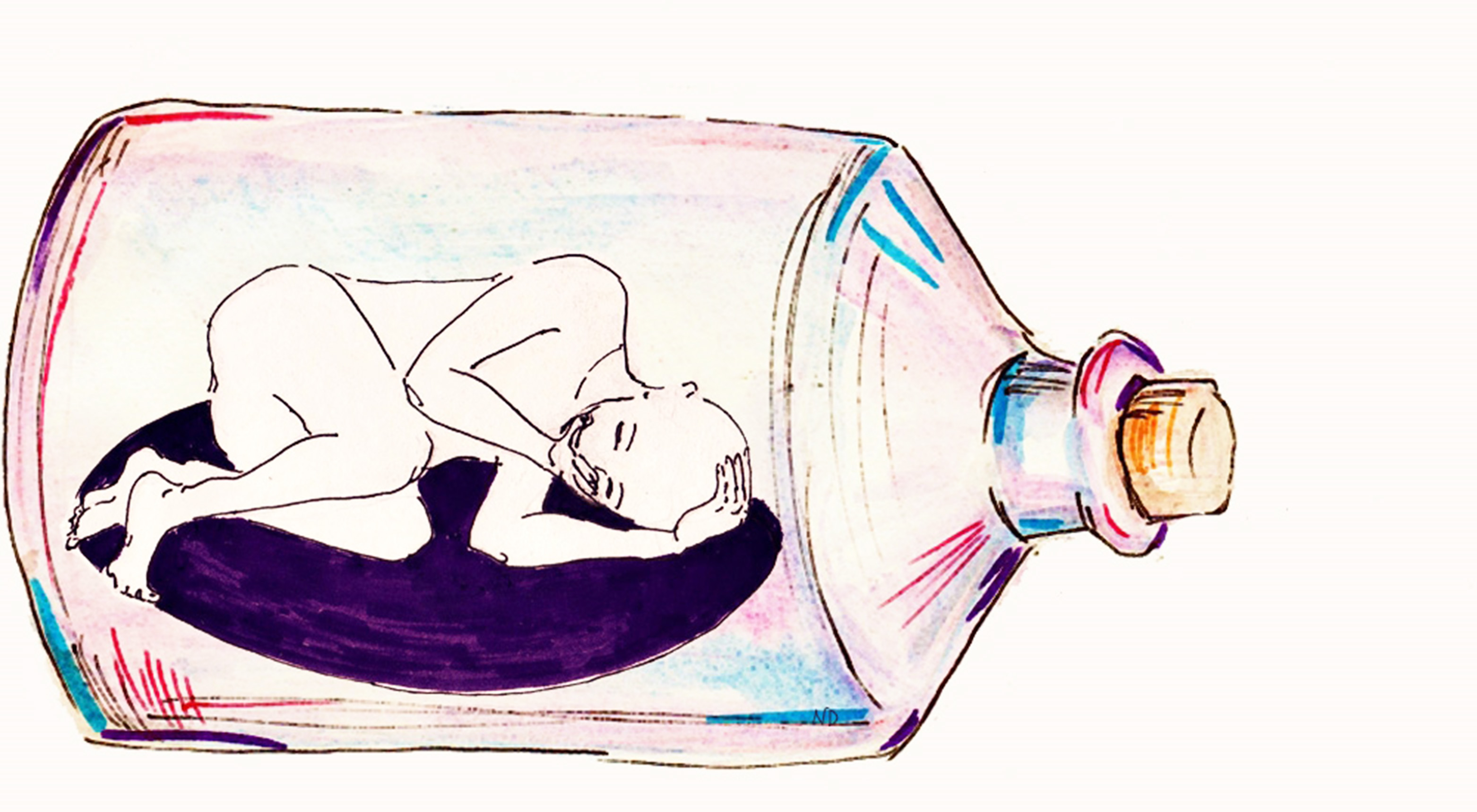

If we really want to combat the issue of child abuse in Ireland, we need to need to acknowledge the fact that we are ignoring the real crux of the matter because we find it difficult to discuss. Do we, as a country, first of all, accept that paedophilia is a mental health issue and, if so, do we actually want to help people who suffer from it? Currently, there are no structures in place to accommodate individuals who seek help over paedophilia. The condition must go unsupported until it manifests itself in a criminal offence. Once there is a victim and a conviction then the state will intervene and offer the individual, who is now a sex offender, support in the form of the Sex Offender Management Policy.

The safety of children is currently being protected by preventing child abusers from repeating offences, which is a very small proportion of cases. The safety of children, alien as it may sound, is to be improved by helping paedophiles. If we really want to combat the sexual abuse of children, then paedophilia, which is not synonymous with sexual abuse, needs to be dealt with for what it is, a mental health issue, not as a crime. It becomes a crime when a child is affected and children are being affected because the problem is going unchecked.

“Do we, as a country, first of all, accept that paedophilia is a mental health issue and, if so, do we actually want to help people who suffer from it? Currently, there are no structures in place to accommodate individuals who seek help over paedophilia. The condition must go unsupported until it manifests itself in a criminal offence.”

Putting structures in place to help paedophiles deal with their issues before it manifests itself in child abuse is the first step. A precedent exists in the UK with Stop it Now! (a group supposedly catering to the UK and Ireland yet without an Irish office or Irish specific contact information) and Germany with Don’t Offend. I asked TD Denis Naughten, who is proposing the Child Sex Offenders Bill, what he thought of the way that paedophilia was currently being dealt with. “There’s absolutely no doubt about it that there needs to be a far more rounded approach taken with the issue. It’s not just a criminal adjustment issue. If there are people who find themselves in that situation they should be able to access support without having to end up in prison before supports are offered to them. I think it is an area that needs far more resources. The whole sexual offences area needs far more resources, both from a mental health point of view and in relation to prevention.”

However, the solution is not as easy as simply putting structures in place. Do we really believe that anyone would use them? The stigma that’s attached to suffering from paedophilia is one of the most entrenched and hate-fuelled in Irish society today. If we want people to seek help with it as a mental health issue then it has to be normalised. It’s not talked about as an illness largely due to how the media tackles it, which is strictly in criminal terms. Currently this is also the only way the state deals with it.

One of the biggest mental health stigmas we’ve dealt with (and are still dealing with) in Ireland is suicide. Suicide, regardless of the causes, was a criminal offence in Ireland until 1993. Before 1993, an individual suffering from depression in Ireland was doing so in a society largely unwilling to acknowledge their problem and in a state where adequate services were not in place to deal with the issue. If the depression ultimately ended in suicide, the individual became a criminal and was, unfortunately, often seen as a source of shame. Suicide could never have begun to be combated if the stigma was not tackled first. And stigma cannot be tackled without public discussion. Denis Naughten, although he agrees that systems should be put in place, does not think that paedophilia as a mental health issue should be introduced to the public forum.

“In relation to suicide, the reason why it’s so openly discussed is because people have been afraid to talk about it and talk is very important, particularly in relation to depression and suicide. I don’t see anyone who has paedophilia-type tendencies openly talking about that to their neighbours or relatives. What is important is that the treatment systems are put in place.”

“People need to know that those supports are available out there, but to compare it to the issue of suicide, to normalise it is the wrong word, but to openly discuss it in the way suicide has been discussed, no. And I would not like to see resources being used in relation to that.” But again, what is the use of having resources if the stigma means no one will use them? “There’s huge stigma attached with mental illness anyway and I think that is something that needs to be dealt with in the broader context of mental illness. I would be very wary of picking this particular illness and isolating it from general mental illness. It has been done in relation to suicide. There was a strong justification for it in relation to suicide.”

Is there not a strong justification for discussing paedophilia? I would have imagined protecting children and people with mental health disorders would be a strong justification. Part of Naughten’s reason for supporting the introduction of a structure to deal with paedophilia was that “If you take the focus on protecting children, then there’s absolutely no justification for not putting those supports in place.”

“Naughten said ‘There’s absolutely no doubt about it that there needs to be a far more rounded approach taken with the issue. It’s not just a criminal adjustment issue.If there are people who find themselves in that situation they should be able to access support without having to end up in prison before supports are offered to them.I think it is an area that needs far more resources. The whole sexual offences area needs far more resources, both from a mental health point of view and in relation to prevention.'”

When asked if the systems should be in place to help the actual individuals suffering from paedophilia he said that “They are coming forward hopefully as seeing that they themselves are risks to themselves or to someone else.” He stopped short of saying that the introduction of a system would also be positive because it helped the paedophiles themselves, that is to say, helped them with a mental health issue and from becoming sex offenders. Naughten himself demonstrated why we need to turn the mental disorder paedophilia into something that can be discussed; by sufferers, their families and by the media.

At the moment, despite our 21st century romance with promoting mental health, we don’t want to help sufferers of this particular condition because it’s politically toxic. Naughten was reluctant to even say the word, instead preferring “this particular issue” and the bizarre “paedophilia-type tendencies”. It’s clear then that there needs to be a serious discussion had about paedophilia and child abuse in Ireland, but not along the line that are being touted today. There are currently two huge problems. The first is the non-existence of a framework to deal with one of the most pressing mental health issues in Ireland today and the second is child abuse. We’re currently ignoring the principle of cause and effect. If we don’t address the former then we won’t be able to combat the latter.

Normalising paedophilia does not mean normalising child abuse. The first step is putting a system in place as exists in other countries, but if we want people to avail of these services then we can’t continue to use the word paedophile, or worse paedo, as synonymous with child abuser and monster, because it’s just factually incorrect.

People are wary of accepting paedophilia as a mental health condition for fear of it offering an excuse for child abuse. Some might wish to see paedophilia unrecognised as a mental health condition. This would leave us back where we started. If people can’t seek help, then their condition will worsen and, for paedophilia it worsens in an environment wherein even if they tried to seek help they would be ostracised. The only way to improve the situation, from both a child safety and a mental health perspective, difficult and all as it may be, is with public discussion.