Sarah Malone

Contributor

Over the past few days, I have followed the #YesAllWoman hashtag, as women all over the world reacted to the story of the mass shootings perpetrated by Elliot Rodger and the responses to it both from mainstream and social media. I also sat down and spent over four hours reading Rodger’s My Twisted World manifesto, which charts the development of his misogynistic ideology from the age of six right up to his planned Day of Redemption, during which he shot and killed six people, and injured 13 more.

What has struck me, and many other women I know, is the unwillingness displayed by the media and others to discuss and confront Rodger’s self-stated motives for carrying out the attack. There are many people branding him as simply “crazy”, paying little thought to the stigmatisation of mental health that this carries, or the fact that individuals suffering mental health problems are more likely to become victims rather than perpetrators of abuse. There are others who wish to shape the discussion around gun control in the US, as if this man would not have been a risk otherwise. This in spite of the fact that three of his victims, his roommates, were stabbed to death, and most of the injured were hit with his car.

“You girls have never been attracted to me. I don’t know why you girls aren’t attracted to me, but I will punish you all for it. It’s an injustice, a crime, because… I don’t know what you don’t see in me. I’m the perfect guy and yet you throw yourselves at these obnoxious men instead of me, the supreme gentleman.”

Rodger’s manifesto

However, after the initial wave of reports and reactions, I saw another reaction, particularly after watching Rodger’s chilling YouTube video posted in advance of the attack, and reading excerpts from his manifesto. Women started to wonder how the actions of this man, who set out to murder women he believed to be withholding the sexual interaction he so rightfully deserved, were not being recognised as the war on woman he so clearly wished the world to know it was. I wondered how anybody could read Rodger’s story in any detail without seeing it as an extreme manifestation of male entitlement to women. I wondered how people could glaze over the overt racism and white supremacy shown in his anger and disbelief that the white women who spurned him would instead choose to date or sleep with men of colour, and the fact that four of his victims were men of colour.

I watched as commenters both in Ireland and abroad dismissed these concerns. Instead, the women who raised questions about a culture that would lead a man to believe that sex with “attractive” women is his right were accused of man-hating. His “punishment” of the women he viewed as responsible for denying him, and the men he viewed as unworthy of their attention in comparison to a “gentleman” such as him, were simply the actions of a madman, they claimed.

Irish Times FacebookAnd so the #YesAllWomen hashtag was started. It was sparked by a conversation between a writer called Annie Cardi and another woman whose identity is private in order to draw attention to the fact that what happened in Isla Vista this weekend was not just the random acts of a crazed lunatic, able to be written off as mental health issues and a country with too many guns. What women know all too well upon reading excerpts from Rodger’s manifesto is that entitlement to the bodies of women does not exist in this man alone. It does not even exist solely in the pick up artist or seduction community. It exists everywhere.

I do not know a single woman whose appearance is not commented on, often loudly and in public, and often by men who clearly do not mean the woman on the receiving end of it to consider it a compliment. I do not know any woman who has not been subjected to unwanted groping and grabbing by men in pubs and clubs, and I know few who have not provoked aggressive anger from a man by spurning his advances. I do not know any woman who has not at least a passing familiarity with holding her keys as a weapon, or any woman who does not have a list drilled into her head of the “correct” way to act in order to avoid being sexually assaulted. I know altogether too many women who have been raped and never reported it, believing (sadly accurately, given our country’s record on prosecuting violent men) that little would come of it.

And it is not just men who are strangers that display entitlement to the bodies of women. The Rape Crisis Network Report of 2011 revealed that in 90% of rape cases, the perpetrator was known to the survivor, a truly terrifying statistic. I am often accused of “misandry” when I talk about the violence that men as a class perpetrate against women as a class, and in this situation it has been no different.

I hear deflections of “not all men!” – as if that is something that is being claimed, as if a conversation about women and the clearly numerous amount of men who feel entitled to our bodies must be a direct attack on all men, as opposed to on a society that constructs masculinity to be synonymous with dominance, power and sexual aggression. This willingness to brush things, both large and small, aside as the work of a few horrible people, a few crazed narcissists, is destructive and damaging. It allows abusers, who usually do not look or seem any different to anybody else, to hide in plain sight in our communities. It allows the many ways in which women are made to feel unsafe in their own cities and homes into “just one of those things” – when instead they are all symptoms of a society in which women’s bodies are objectified, and women are often considered little more than decorative pieces for men to collect and admire, a society full of numerous men who react with rage, and as we have seen here, sometimes murderous rage, when women behave as the independent and autonomous beings that we are, and when we derisively refuse to be shoved into the roles society has dictated to us.

I am constantly dismayed that the reaction is often “not all men!”, rather than “wow, that many men?”. We know it is not all men, but if men know just how many it is (enough that #YesAllWomen have these stories), and can only muster a response of “not all men though!”, that shows a self-interest that makes me wonder if they grasp the true scale of the problem at all, or if they are willing to show these issues the light of day they so desperately need in order to effect change. It makes me feel like men are unwilling to confront the idea that with so many perpetrators of abuse, with abuse most often perpetrated on women close to the abuser, and with so much stigma attached to abuse that many keep it a secret, that the abusers are in our communities.

I have seen this willful ignorance before, as I have known more than one group of male friends who closed ranks around the perpetrator of abuse once the woman revealed what had been done to her, or who walked the line of “well nobody can really know what happened” – which most often has no effect on the perpetrator and leaves the survivor with a choice to stay around their abuser forever or quietly leave their group of friends. It is a story I am sure is familiar to many of you too.

Elliot Rodger is not representative of all men. I do not know a single feminist that believes that all men are abusers. But as long as we refuse to challenge the endemic sexual entitlement, toxic masculinity and misogyny in our society, then too many men will be abusers, and #YesAllWomen will have to pay the price for that.

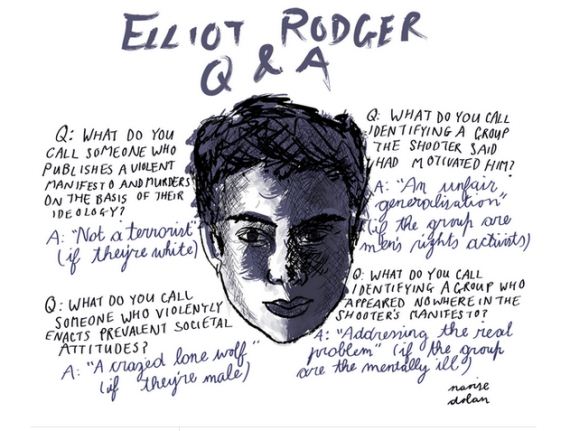

Illustration by Naoise Dolan. Naoise’s work can be viewed here.