Somewhere along the southern wing of the Musée d’Orsay’s niveau médian, some of Eugene Carrière’s work hangs alongside that of his fellow symbolists. Though not as immediately gripping as some of the more famous Impressionist pieces on show, it does have a certain resonance. Carrière is apparently known for his sepia-toned or monochrome style. Despite this, I found his rendering of the Place Clichy by night quite true to life, particularly as I entered said place from the Pigalle direction, heavily sedated, and with my arm suspended in a sling. His suggestively nebulous forms sprang to mind, even if it was broad daylight at the time. At the very least, the thought kept the rising ache in my newly injured shoulder at bay.

It had been nine days since I had made for Paris to complete the same Residence Abroad Requirement that had taken me to the south coast last summer. My failure to maintain a steady income then had left a chip on said shoulder. In E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, the author describes the difference between a round and flat character: the former being a character who changes over the course of a narrative, the latter being who doesn’t.

Returning to France with unfinished business, I was determined to leave this latter category, to which I believed myself to be relegated. (After all, how could the narrative arc mastery of the French language by a plucky TSMer be completed if the main character couldn’t get a job in France?) I would no longer be a person in stasis, unable to learn from my experiences and therefore bound to repeat them. This time would be different: the email confirmation of work in the Loire Valley, however voluntary, made this progression seem feasible. I gathered what cash I had left from the various, and variously lucrative, part time gigs I’d had in and around campus, plus some substantial parental funding, and looked forward to an improving week in Paris.

Thankfully, there was one thing I had learned during my tour of the Riviera and its environs: I began to understand the importance of spending time in France in order to ‘talk the talk’. “Excuse me, my postillion has been struck by lightning” reads one, once no doubt hysterically funny, example of abstruse phrase book specificity. Firstly, the word postillion has sadly fallen out of everyday use due to a fall in demand for full time carriage drivers. More importantly, such fastidious, and ultimately impossible, preparation for the habitual seems completely redundant in tutorials where one can spend up to five minutes chewing a sentence over, or even remain completely silent.

It is only when living in France that it becomes apparent that a single busy afternoon presents up to a hundred compromised postillions, each of which must be delicately explained or interpreted swiftly, if their wellbeing is to be ensured.

My first reminder of these difficulties came after only 24 hours. On my way out of the hostel I asked Aurélie, the cool concierge, if she’d seen my sunglasses. Some subtly misplaced inflection, or my failure to mention the glasses had been misplaced, led Aurélie to concede they were a very lovely pair and that she wouldn’t mind some herself. While these small misunderstandings add up to a creeping sense of failure, there are also unexpected instances of encouragement. As a student whose performance in oral exams felt, at best, deceitful, I was refreshed by the number of Parisians who deemed my level of French sufficient. “If I am speaking French, that is always a very good sign,” one of my new friends remarked, in English.

Not all reinforcement is this positive though, as I learned after having the misfortune to inadvertently photographing a waiter as he came into shot. “Do not photograph me when I am working” he exclaimed, in French. After examining the photo, I had to admit it was most likely his work attire that prevented him from dominating the shot as he would have liked.

Despite the odd moment of linguistic tension, my stay went by innocuously enough, which might explain my panic on the penultimate evening. The last two nights I had become a regular in the lobby and had built up an impressive, hostel-wide array of acquaintances as a result: there was the Argentine duo that consistently worked their way through several cartons of wine each day; the trio from Austin, Texas with whom I’d visited various spots recommended by returning Erasmus muckers (Oberkampf etc.); and the man from Birmingham who preferred Granada. Despite all of these new mates, I was now eager to hit the town again, but the Texans had gone to Versailles and the popular choice in the lobby was a ticketed Montparnasse pub-crawl.

At €35 euro, a selfie in the precise spot where Hemingway may well have vomited (had Fitzgerald not surreptitiously offered his satchel), seemed a bit dear. Happily, the Argentine duo had decided they’d spilled enough red wine on the white marble steps into reception and were rounding up a group to check out some haunts approved by Aurélie. What I envisaged was a semi-sophisticated night out in Paris. What unfolded was, in fact, an incredible evening; a procession of apparently spontaneous and increasingly hilarious events. While the night was outrageous fun and the streets of Paris provided a better backdrop than Athy or Carrigaline, I was only in Paris a week and I wondered if was I now missing the point somehow. The feeling diminished as we made our weary way home and the Haussmann grid revealed a surprisingly labyrinthine potential, and it wasn’t long before it was time to retire. The following day I decided four hours of sleep was probably the going rate that morning and made for the Louvre. After a full day of perusal, which encompassed some strikingly mute Sumerian sculpture and Louis 16th’s multi-story teapot, I took a long meandering walk in a ceremonial farewell, of sorts, to the city I had wandered through over the past nine days.

Hours later I was back in the Louvre in slightly more surreal circumstances, contending the crowds in the Grande Galerie. It was, literally, a nightmare. The true nature of the situation only became apparent when I fell from my bunk and hit hostel’s oak floor, shoulder first. “Mate, that wasn’t you hitting the floor was it?” asked an Australian roommate I’d befriended that morning upon finding me. I replied it had in fact been my postillion. The joke didn’t go over, but he fetched ice from reception all the same. Violent dreams run in the family and on an unprotected bunk I guess I was asking for it. After an unsuccessful attempt to sleep it off, I suggested to Aurélie that she call me a SAMU, the French equivalent of an ambulance. That is, if that was what she thought was the done thing around here. I presumed I’d misunderstood the kind SAMU driver when he enquired as to the means by which I would pay the €180 call out fee. Five minutes later, we were standing, my arm tucked into my t-shirt, at a resolutely unyielding ATM. Having cut a deal with the driver for pretty much everything I had left, I was looking over my X-Rays with an increasingly solemn doctor. A broken clavicle, the same injury my Grandfather supposedly sustained wrestling his brother at a similar age. “T’es devenu un somnambule alors!” I was informed by a fellow patient. My Grandfather had also been asleep at the time of his injury, which makes him a slightly more advanced somnambulist than myself.

Things began to progress avec une telle vitesse as it became apparent I might have been heavily concussed. I was extensively examined and found to be in surprisingly good shape. The report even went so far as to conclude, much to my parents’ amusement, that there was no alcohol in my system. “Your French is excellent,” offered the nurse who fitted me with a cast (which was subsequently denounced by the triage staff at Cork University Hospital). I then bid my fellow invalides farewell and I was at large once again. It had been 20 minutes by the time I had sharpened up enough to negotiate the hasty Western Union transfer wired by my parents/parrineurs. I then made my way out to Charles de Gaulle through a sequence of Tramadol-induced hallucinations. By the time I had finished an inadvertent tour of Terminal 2 it was almost time to board back over at Terminal 1. It was in the triage room back in Cork that I realised, with a wave of remorse breaking in between those of nausea, that I was still yet to join the French workforce, voluntarily or otherwise.

I began to wonder if I had learned anything from the experience. At first, my mind ran sullenly over the role external forces had played: the French Department did not allow students to travel to France for a full year as Junior Sophisters, and that the TSM office stipulated the somewhat inadequate Residence Abroad Requirement as the alternative. I was not proud of this response and a sudden flurry of very adult thoughts intermingled the next wave of nausea: my own time in France was my responsibility and if I wasn’t going to spend time to engaging with the powers that be in order to address the ways in which students feel restricted by the Erasmus program, I had to work with what I was given. Ultimately, I should have gone in my Senior Freshman year.

This apparent emotional growth all seemed a little too tidy, however. All of these revelations seemed a little obvious, the conclusion a little too easy. I began to wonder if this was a genuine life experience or just another good story I had spoiled by forcing a rather trite moral resolution. Had I been spared a genuinely improving experience, and two weeks hard labour, by a bone broken in humorous circumstances? Would I have suffered an even more serious, power tool related, injury in the Loire Valley as a significant portion of the family would like to believe? Did the location of the accident invest the incident with a certain unwarranted charm? Did an affirmative answer to any of these questions doom me to further Fosterian flatness of character? Would I ever learn? At any rate, I looked into my empty wallet and was thankful that I at least had an alternative currency upon which I could dine out over the coming months.

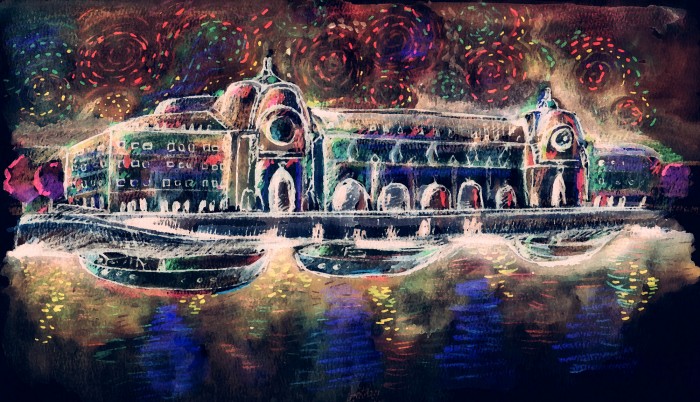

Illustration: Natalie Duda