“On a Tuesday night in the summer I tried to paint a train bridge that spans Portobello Road in West London with posters showing the revolutionary icon Che Guevara gradually dribbling off the page. Every Saturday the market underneath the bridge sells Che Guevara t-shirts, handbags, baby bibs and button badges. I think I was trying to make a statement about the endless recycling of an icon by endlessly recycling an icon. People always seem to think if they dress like a revolutionary they don’t actually have to behave like one.”

As usual, Banksy, the celebrity graffiti artist who now makes a living selling “street art” to rich people, was not being quite as subversive or as original as he thought when he said the above. His point has been made many times by sneering conservatives, superior liberals, and not a few snobbish leftists. The criticism has been so often repeated that it has become part of the Guevara T-shirt cliché itself. The charges are threefold: those who buy Che t-shirts are fakes – faux-revolutionists who think that buying a shirt is a substitute for actual political action; they are also hypocrites or patsies – they either ignore or are ignorant of the fact that Che merchandise is manufactured by profit-seeking capitalists, the very people that Guevara regarded as class enemies; and, finally, they are naïve or callous, neglectful of the Argentinian revolutionary’s bloodthirsty desire to liquidate his opponents.

In this article I’d like to rebut these charges. I won’t linger for long over the third accusation – that Guevara was a sort of Marxist berserker driven into murderous frenzies by his hatred of the bourgeoisie. To refute this properly would require a longer column. All I’ll say is that the use of political violence is not something which is always and in every situation wrong. Any even partly-honest person will admit that there are certain historical situations, or at least certain hypothetical scenarios, in which it is justified. So I don’t think it was unethical to use guns to overthrow a dictator, as the Cuban revolutionaries did, but I think it would have been politically preferable to base the military force on an organised labour movement.

Anyway, now that we’ve set aside the historical question we can consider the other two charges in a semi-unified manner. As you might have guessed, I own a Che Guevara T-shirt. I don’t wear it much anymore – not because I’m embarrassed about it, but because it’s a bit old and tattered now and has a big hole in the back. I bought it around seven years ago in a depressing and charmless tourist town near Barcelona. At the time that I bought it, I might well have been considered the very person that the t-shirt-despisers have in mind when they picture the average Che-merch consumer. I was very politically naïve and had only the faintest idea of what the words capitalism or communism denoted. I also had, at best, a very foggy notion as to who the guy with the beard and the beret was. (In my defence, I was fourteen.)

Back in Ireland, I wore the T-shirt to the swimming pool one evening. I used to go there every week to do lifeguard training. The training was dull but I had a friend who also went there who I liked to talk to while we were togging in and out in the dingy changing rooms. My friend was, at the time, a rampant supporter of Fine Gael (though later on he crossed the tracks and joined Sinn Féin). So when I wore the Che T-shirt to training one day, he accused me of being a commie. I had considered myself, in a vague way, a sort of leftist, though certainly not a communist. But he kept calling me one and striking up arguments about it so, naturally, I decided to look up this Che guy and investigate the ideas that he stood for. This (in a stylised way) is how I became a Marxist. I read about communism, looking for answers to my swimming pool sparring partner’s arguments. Soon I began to see, in a vague way, what the problems of capitalism were, and how they could be solved by socialism – not the totalitarianism of Stalin and his successors, but the free and democratic society that Marx and Engels advocated, in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”

This story is, of course, only a personal anecdote. There aren’t any statistics on the number of people who have bought Che T-shirts and subsequently became socialists. Still, it’s not unreasonable to suppose that others may have followed the same path. The prevalence of Guevara’s image has almost certainly inspired people to find out who he was and why he did the things he did – in short, far from being politically empty, it has served a certain propaganda purpose for the cause that Che and his fellow revolutionaries espoused.

But even if this is conceded, will the critics still not say that it is hypocritical for self-professed socialists to buy into what has effectively become a consumerist icon, a big, profitable brand, just like the Nike swoosh and the golden arches? This position ignores an obvious fact: that we live in a capitalist society and pretty much everything we buy is made in a capitalist production process. Unless she is to decamp to a desert island and sustain herself on roots and berries, a committed socialist cannot simply live outside of capitalism. Marx was all too aware of this and frequently denounced those “utopian socialists” who held that capitalism could be superseded by creating a communist micro-society within the confines of a bourgeois state. Marx knew that capitalism must be overthrown from the inside, and he thought that this process would occur by seizing onto, and pushing to their revolutionary conclusion, certain “contradictions” generated by capitalism. For example, one such major contradiction is that, with the growth of capitalism and the expansion of the capitalist production process, more and more people are sucked into the working class, thus creating an ever greater mass of oppressed persons itching to cast off their fetters. Therefore, Marx says in the famous manifesto, what the capitalist class ultimately produces “are its own grave-diggers.”

Living as we are in a capitalist society, we must buy clothes that are made in a capitalist production process. So why not buy clothes with the likeness of a revolutionary icon, a robust “brand” with the power to penetrate the popular consciousness with a radical political message? There’s no reason why political radicals should feel ashamed about wearing a Che T-shirt. In fact, it’s not the T-shirt buyers but the capitalists themselves who are the dupes. In their heedless pursuit of profit they have become unwitting propagandists for their class enemies, producing another shovel for their own gravediggers.

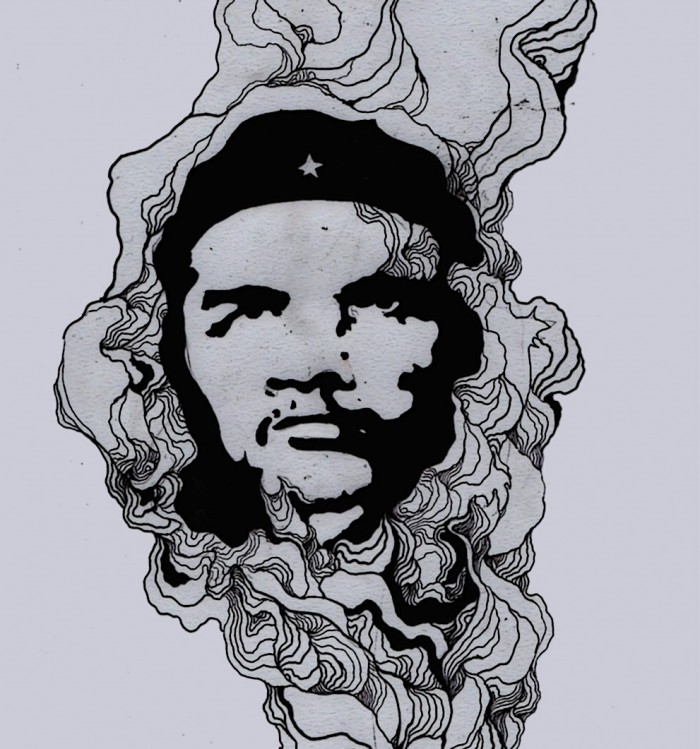

Illustration: Sarah Morel