With these thoughts in mind, I wanted to see how students feel with the services provided to them — both in college and the outside world — and measure their experiences against those of the current campaigns around mental health. The important thing to keep in mind are the responsibilities of the health service professional. When someone who is in need of help puts up their money and builds up the confidence to go to a doctor, we should expect that professional to behave in a professional way and to do everything in their power to fully diagnose and treat the symptoms presented. After all, if we’re told that depression is a disease like any other, than it should be treated with the same seriousness and dedication that others are.

One student, Abby, found that her experience led her to question how well doctors are trained to deal with mental health issues. When she was a DCU student seven years ago, she sought help from the college doctor after a period of self-harming, going into the doctor’s office shaking and crying. “I showed her my cuts and told her how I’d been feeling shit all the time and that I was crying on a nightly basis,” Abby told me. Going into the appointment, she knew that she wanted to either get some medication or get referred to a specialist who could assist her further. The doctor was non-responsive. “She looked at me like I’d asked her to sell me some heroin and told me that someone would contact me soon about services that were available.” The doctor never got back to her with any details, nor did she mark anything on Abby’s file. Her experiences seeking help led her to avoid seeing a medical professional again until three years later. She feels positively about campaigns to promote talking, something which during her youth was considered ‘emo’: “I’m 27 now, I think people who are five or six years younger than me who grew up with social media are a lot more aware of mental health issues and have a better understanding of them.”

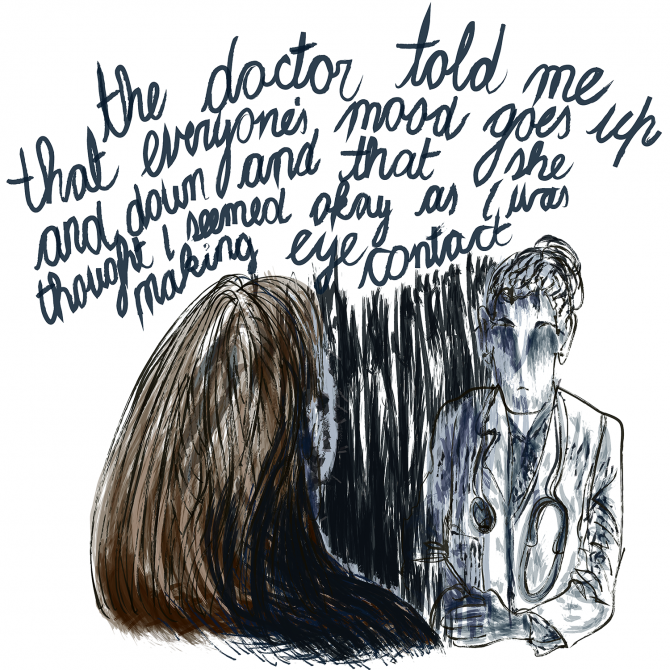

David is a UCD student who went to a GP because the wait to see the university’s counselling service was eight weeks. “The first time I went, the doctor very kindly explained that everyone’s mood goes up and down sometimes and that she thought I seemed okay as I was making eye contact.” Like with Abby, David was not referred on to any specialist nor was any note made on his file about his condition. “I was so annoyed, I felt that she didn’t take me or my concerns seriously and effectively reduced [the depression] to being a moody teen,” he says. “I felt that while I wasn’t doing awfully at the time, others could’ve been and that it would be very bad way to deal with them”.

A few years later, he went back to a GP after a bad experience with the UCD counselling service. “They sent around an email to everyone on the waiting list saying they would reimburse receipts if people went to private places instead. Private places wouldn’t be as familiar to students. But this only meant that people who could afford to pay upfront would be able to go — even though you’d be reimbursed you still needed spare cash.” To try and alleviate the numbers on the waiting list, UCD sent out an email about a “Mindfulness Course” which was being organised by some of the counsellors. The email was sent to everyone on the counselling waiting list, however it wasn’t bcc’d and all the recipients of the email were visible to all the other recipients. “Everyone has an email but there is a number version and a name version for the same account. They used the number version so you couldn’t see names, but you could see the student numbers of everyone [on the list]. It was surprising to see and was a stressful fucking mess for someone who was already a stressful mess,” David said. This lack of oversight and care in dealing with students in a precarious situation was something that contributed to David abandoning the college health services and having to pay money to see not always helpful GPs.

“They sent around an email to everyone on the waiting list saying they would reimburse receipts if people went to private places instead. But this only meant that people who could afford to pay upfront would be able to go.”

Trinity student Emma has had experiences both outside and inside the college counselling system and also with the college disability service. She told me that while having a psychiatric evaluation in a clinic the doctor decided that all her issues had an explanation and that unless she displayed “damaging” bipolar symptoms they wouldn’t give her any further appointments. “Also I was told I should get my act together or drop out of university, because everyone else was able to deal with academic pressure,” she says. “I had a panic attack about a minute after leaving, and it ended quite badly because it screwed with my already messed psyche at the time”. On trying to change her medication because of the side effects she was suffering, she says “the doctor told me they weren’t going to change my dosage or medication, and if I was that unhappy why hadn’t I just stopped taking them?” Within a week of taking that advice, she had had a breakdown — not surprising since suddenly going on or off anxiety medication or anti-depressants can be detrimental to your health.

Emma also presents a strange series of events which portray the doctors’ mentality as being reminiscent of those in Catch-22. “I’ve also been told that if I’m able to seek help, it shows that I’m not in that bad a way, because if I was really depressed I would be too isolated to do so.” The disability services have also issued ultimatum like questions of her life outside college; during her one conversation with her assigned disability officer, “he asked me why I had a job and an internship if I couldn’t even deal with college work. There is very little understanding of how mental illness will not always be the depressive or manic episodes and that a lot of the time you can function as a human being.” The lack of any empathy and understanding shown by these medical professionals towards a young vulnerable person is extremely shocking.

Andrew, a student in UL, began treatment for depression and paranoid anxiety towards the end of the second year of his arts undergraduate degree and continued the treatment on through the completion of his degree and into his postgraduate studies. Echoing comments Emma made about doctors and administration being obsessed with medication, Andrew was unnerved by his first visit with a doctor in a Limerick hospital. Seeking medication wasn’t what he had in mind but found the perceived relationship between drug companies and medical professionals off-putting. “My anxiety was exacerbated by the proliferation of drug company merchandise in the doctor’s office. A patient is not made feel at ease when his doctor writes with a Lexapro pen and drinks from a Lexapro mug. The first thing you notice is how quickly after admittance to a hospital they begin to medicate you”. As with other people who spoke with me, Andrew feels that he has been passed around from doctor to doctor and because of this his file has been ignored by doctors who don’t have the time or desire to get to know him and his history. “There is no guarantee that it is the same doctor you saw the previous appointment. In my seven years of treatment I have only on one occasion had the same doctor on two successive visits, in fact, 80% of the time the doctor I encounter I have never met before. As each doctor is meeting you for the first time, and has neither the time nor the desire to read your file, he/she asks you to recount the full story of your diagnosis. This turns each visit into an arduous event, which you may have entered in good health, but left reminded of all your issues.”

“The issue of sexuality is one that makes Irish doctors particularly nervous.”

Touching on an issue that I have experienced along with some of my peers, he says that some doctors are not equipped to deal with issues of sexuality. Indeed, when you are a patient and entering into a doctor’s office, regardless of how related to your depression you sexuality might be (through bullying, physical/verbal abuse), it takes a lot of courage to trust a stranger to be as accepting towards your sexuality as you need them to be. “The issue of sexuality is one that makes Irish doctors particularly nervous. Despite the fact that the apparent incompatibility between my homosexuality and the deep faith in which I was raised was one of the chief causes of my unhappiness, my doctors have been unwilling to discuss it.” In my own life, once a doctor refused to link harassment received on the street with my sexuality, believing the reason I received such abuse to things like my appearance and dress sense. “Not that that makes it excusable,” he told me.

Another Trinity student, Rebecca, organised a visit to the GP just after she turned 18. “I had been feeling terrible for at least six month, was self-harming and suicidal and did not know what to do. I had been encouraged to make an appointment with my GP by friends, and finally by the SU Welfare officer. I never wanted to talk to the GP and was convinced that it wasn’t going to help or make any difference to how I was feeling, so had never even considered the idea before”. Nerves were yet again a factor in delaying her visit to the doctor. They flared up on the morning of the appointment, making it more difficult for her to discuss her condition. “I was by myself and considered running out of the clinic half a dozen times before they called me in. When I finally got to sit down I was so worked up that I didn’t think I’d be able to say anything at all. I had a middle aged male doctor. He asked how he could help and all I managed to say was ‘I’m not happy’ before I choked and couldn’t get any more words out. He asked some more questions, seemed disinterested and almost bored and finished up by saying that he’s sorry but he couldn’t do anything straight away, but I should come back in two weeks if I still felt depressed.” She later visited a different GP and found that her manner was much more open and accepting.

The issues raised by these students — all different ages, at different stages in their lives and from different institutions — show that there are still a lot of problems with the way the Irish medical establishment deals with mental health problems. If you are a young person who has completed third level education, free mental health services are probably not available to you. Finances are a huge source of problems, and worrying about the money needed to get your mental health checked out is a double trigger for someone who is already in a distressed state of mind. Even if you seek help from the college counselling services, the long waiting lists take their toll.

Talking does help in and of itself, but going to a doctor with the expectation that they will be able to understand all the complications that may be contributing to your mental illness can leave you feeling shaken; if you are able to talk but they are not able to listen. We need to switch the focus away from simply telling people to seek help. Encouraging those who require assistance to speak about their experiences is an imperative, but it is not something that happens in a vacuum. Someone needs to listen, and we need to ensure that there are enough resources and properly trained professionals to give the help that people need while following best practice and protocol. There is no room for error.

All names mentioned are pseudonyms.

Illustration: Naoise Dolan