Going to college to do an undergraduate degree costs twelve thousand euro and three or four years of your life. So why are you here? “To get a job”; “to learn”; “to have a good time”; all answers you will hear if you ask the question, and all valid in their own right. But the real reason most of us are here is because it’s just what you do. Whether you went to a fee-paying school where going to a top university was expected, or a disadvantaged community school where progression to third level was seen as a great achievement – your secondary school experience was designed to send as many of you on to college education as possible. Encouraging all children to be educated (and providing the support and infrastructure for that to happen) is a good thing. But in a climate where jobbridge interns often require a bachelors degree, devastating cuts are being made in colleges, and our top universities are sliding down the league tables, our attitude towards exactly what kind of education we encourage needs to be looked at.

A report by the OECD describes the Irish second-level education system like this: “The upper secondary education pathway in Ireland is a large one… with relatively little specific vocational preparation taking place at that level. This results in a strong emphasis upon preparation for tertiary entry within the school system… reinforced by competitive external examinations”. This report is from 2002, but since the introduction of the Leaving Certificate Applied in 1995 there hasn’t been significant reform in Irish secondary education. Roughly 60 percent of school leavers attend tertiary education. Most come to college directly after school, many without having had any kind of job or academic experience beyond the school curriculum. Guidance counselling is poorly implemented, something which is not just the fault of counsellors themselves but of poor organisation at school and national levels and the influence the points system has on views of higher education.

The undergraduate population is rife with apathy and disillusionment. Everyone is familiar with tutorials where few have done the reading, and the experience of throwing together an essay thinking “this is crap but it will probably scrape a 2:1”. This isn’t just because Irish young people are lazy, it’s due to the nature of our entry into third level education. It is not a meaningful transition we make from secondary to tertiary education.

In 2010 the average dropout rate for first year students was about 15 percent across ITs and universities. If dropping out didn’t mean throwing a lot of money down the drain, it would likely be significantly higher. The undergraduate population is rife with apathy and disillusionment. Everyone is familiar with tutorials where few have done the reading, and the experience of throwing together an essay thinking “this is crap but it will probably scrape a 2:1”. This isn’t just because Irish young people are lazy, it’s due to the nature of our entry into third level education. It is not a meaningful transition we make from secondary to tertiary education.

Career misguidance

In fourth year, you do the DATs, which tell you where your skills lie based on a single test and offer a list of possible careers with little explanation as to why you should pursue them. If you have a reasonably high aptitude for most things, you’re told to do whatever you think you might like. You might also do a “preference test”, to tell you what is it you’d enjoy. Mine told me to be a farmer. I’m sceptical that had I really wanted to be a farmer, my Dublin school counsellor would have approved or given me any help in that direction.

At the beginning of sixth year, you are encouraged to take a day off school and visit the Irish Times ‘Higher Options’ exhibition, where instead of meaningful direction you can avail of hundreds of shiny prospectuses all telling you why studying everything, everywhere, is absolutely fantastic and the right choice for you. Then there is the competitive mania around the leaving cert, with articles about the usual geniuses who got 600 points (or 625 points as some might like to remind you) filling the news. This sense of competition encourages an uncritical passage from second to third level. If you can do it, you should do it. If you were the best in the class at physics, then science is probably for you.

This blasé attitude towards tertiary education, where the sole focus in schools is on academic exams and progression to academic third level courses, is bad for a number of reasons. For a start, many people are simply unprepared for college. Although most people enjoy it, it might be more fulfilling and ultimately more useful if they were better informed upon entry, or encouraged to wait a year or two rather than rushing in to what will be a defining part of life. Postponing entry could prevent many people who choose a course simply because they feel they have to choose something from becoming locked into degrees they know they don’t really want to be doing as a result of financial concerns or perceived failure. Students who had some time to reflect on their futures without the clouds of the leaving cert hanging over them would be better placed to make decisions about their continued education and in a better mindset to get all they could from it. Delaying college entry is not unheard of elsewhere – nearly ten percent of UCAS applicants take a year out before beginning college, and gap years are correlated with higher satisfaction and performance levels at university.

False expectations

The secondary system could also be accused of leading people down a path that doesn’t live up to expectations. Many students become disillusioned with their course when they realise it is not the ticket to employment they thought it was. Earlier this month, the inaugural Irish Survey of Student Engagement found that 23 percent of arts and humanities students said they had never looked at how the things they learnt were applicable to a work environment. The stats for science students were lower but still significant, with fifteen percent concurring.

It is becoming increasingly necessary, or at least perceived as such, to do postgraduate study. The ubiquity of level 8 degrees has led to an expectation to do a masters. This is a cycle entered into very casually by schoolgoers who might find themselves having to stay and pay for more years in college in order to gain meaningful employment in their area of study. That college is not a ticket to a decent job in Ireland needs to be explained to school students. In recent years this has been made abundantly clear by stories of new graduates finding it nigh on impossible to gain suitable employment, and the high rates of students actively considering emigration as reported in the aforementioned survey.

Narrowing choices

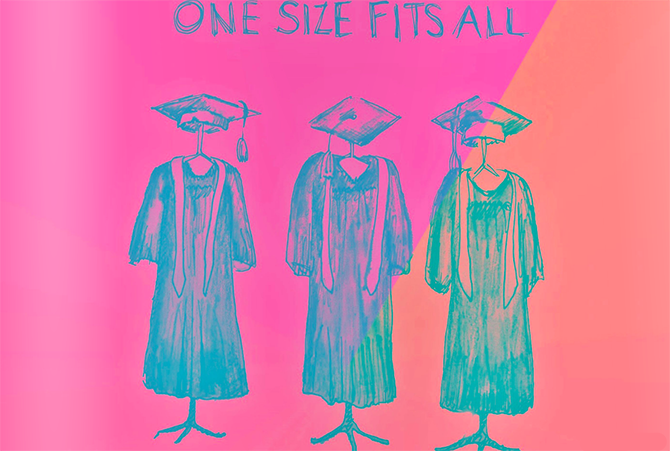

An acknowledgment that college is not for everyone would be a better alternative to the attempted expansion of one-size-fits-all education. This is not only a matter of ability but of happiness, priorities and lifestyle.

The focus on college entry also has the negative effect of narrowing educational possibilities. An acknowledgment that college is not for everyone would be a better alternative to the attempted expansion of one-size-fits-all education. This is not only a matter of ability but of happiness, priorities and lifestyle. While traveling in Austria and Germany last Summer, I was struck by how different the attitude to education was amongst the people I met there. It was striking how they didn’t see university education as the be all and end all of a good education or career. Many of them had chosen to forego it in order to enter vocational programmes instead, not because of lack of financial or academic ability to enter college, but because they simply didn’t see it as the best place to learn the type of things they wanted to learn, and established vocational programmes are available. One man was beginning a residential course in organic farming, another was doing a four year apprenticeship under a master blacksmith, and one girl was embarking on an apprenticeship in a bakery.

In schools there, they have a tiered system, and only certain schools do the equivalent of the leaving certificate, while others offer more practical education. Although such a tiered system certainly has its faults, it does offer inspiration for integrating vocational education into the school system.

The leaving certificate applied and the leaving certificate vocational programme are the current alternatives to the established leaving cert, but tend to be seen as options for people who would do badly in the traditional leaving cert rather than as valuable alternatives in their own right. LCVP is designed to give an opportunity for less academic students to gain more CAO points than they would otherwise, while LCA was set up with the express aim of keeping early school leavers in school and tends to be seen as an easier leaving cert that doesn’t gain students much capital in the employment market. Neither of these options offers meaningful practical education – they are not a true alternative but rather a watered down version of the highly competitive, highly academic school programme that 80 percent of students complete. People who struggle with, or simply do not find fulfillment within such an academic programme should be offered a proper alternative. This could start with vocational opportunities being widely discussed by guidance counsellors in senior cycle in addition to the endless CAO chatter. Alternatives to mainstream college education need to be talked about not just to students who guidance counsellors think need extra help but to everyone, if they are to be seen as a viable option and respected equally alongside academic degrees.

Illustration: Natalie Duda