Fast forward one year, and seven decades, and DU History were hosting a re-unification themed club night to mark the Berlin Wall’s dismantlement, entitled The Wall. The Twisted Pepper was at capacity once again as 99 red balloons descended from the ceiling into the melting pot of old school East German techno beats, juice splash, denim and retro sports wear below. The design of the tickets for this year’s event, modeled on old East German visas, seemed evocative of DU History’s mission: to grant their members temporary access to a space in which engagement with complex moments in world history and good times go hand in hand.

If the recent backlash to the proposed Channel 4 sitcom Hungry is anything to go by, not everyone wants to go there. Described by writer Hugh Travers as “Shameless during the famine”, the show has garnered considerable backlash, from Irish-American website Irish Central in particular, as well as a well publicized, 40,000 signature, petition on change.org and historian Tim Pat Coogan’s holocaust sitcom comparison. Much of the outrage seems to boil down to the idea that laughing at an event as tragic as the Famine is not acceptable.

Finding comic relief

I spoke to DU History about finding comic relief in civil war and partition, as well as the potential pitfalls of satirizing the Famine, particularly when many may be unfamiliar with the event they are supposed to find funny. The promotional material in the build-up to Wind that Shakes the Party seemed to centre on a dual swipe at both the ideology of the Civil War era and modern student drinking culture. An Eamonn De Valera Facebook account announced pre-drinks to be held in the GPO, Boland’s Factory, The Four Courts and City Hall, encouraging would be attendees to “drop (him) a telegram!” De Valera was also unable to pick up his “usual” six cans of Coors Light as his refusal to recognise a Free State police force made requests to see his Garda Age card somewhat awkward. An image depicting De Valera and Michael Collins holding up the Pamplemousse board together at Diceys’ “Thank F*ck it’s Easter Monday” event some time in 1916 served to highlight the pathos of their spoiled friendship. The promotional content also satirised other aspects of college life: another image emerged in which Thomas Clarke and Joseph Plunkett, two lesser known figures in the Rising, are seen manning a “Bakesale for Belgium” stand, outside the “Edward Carson” theatre in the Arts Block. This double-edged approach, which combined some times numerous historical references with instantly recognisable student phenomena proved potent as the event sold out in under an hour.

Club night commemoration

Casting a reflection on students is not the only way to get them involved, however, as the Wall examined student life in a different way. The two events differed in their conception: Irish Steph’s unique incorporation of traditional Irish instruments into electronic music represented (as well as the ultimate acquired taste) the perfect soundtrack for an Anti-Treaty club night, a pre-existing idea. In the case of the Wall, the desire was to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Berlin Wall, which provided the perfect opportunity to celebrate German electro. “Berlin in that period was an absolute hotbed of electronic music. Modern party culture was really in its infancy there. It wouldn’t really occur to us now but up until the mid-80s the idea of a dark room full of people dancing to someone playing someone else’s records was pretty much an alien idea, the only comparable thing to come before that I can think of is England’s Northern Soul scene, or Jamaican sound system culture.”

It seems rather than critiquing the idea of a club night, The Wall traced it back to its source. “In conceptualising the night I poured over Youtube watching videos. People were elated,” says Finnán. By contrast, the promotional video for the event demonstrated a more of an irreverent statement on the discontent of the post-Independence era. The track ‘IRA’s Tweed’ by Irish Steph scored reversed footage of Irish troops entering Belfast, the Eucharistic Congress as well as inspired use of a clip from The Wind that Shakes the Barley. The video was intended to represent a bizarre Republican, Anti-Treaty fantasy in which phenomena perceived as direct results of the Treaty’s recognition by Dáil Eireann, such as the secularisation of Ireland and the Troubles, are reversed.

Another reason the two club nights differed is that there are different concerns to be addressed in representing different events. “Obviously there’s a lot of tragedy associated with the Berlin Wall, but the night that we threw wasn’t about that. The Wall was about capturing the sense of celebration that ran through Berlin as people realised that the city’s division was over,” says Finnán. This presented a difference in tone from The Wind That Shakes the Party where “the humour was drawn from absurdity.” Finding humour in the Famine era would be different again: “A certain tone will definitely be funny, (but) there most certainly isn’t anything funny about the famine itself. But tragedy/sadness and humour often really do go hand in hand. Humour can be viewed as a human coping mechanism: if you can laugh at something, it hasn’t really conquered you… If Hungry is done right, we won’t be laughing at the starving masses of famine-era Ireland, we’ll be laughing with them.”

Controversy

Travers is yet to elaborate on his outline of Hungry, though his “comedy equals tragedy plus time” formula bears some resemblance to DU History’s satirical approach. His most well-known work to date, the radio comedy/drama ‘Lambo’ features the late Gerry Ryan relating a fictitious period in his early career: Ryan endures considerable media backlash for killing and eating a lamb during a survival challenge on the Gary Byrne show. Though vastly different in terms of subject matter, the play demonstrates empathy in examining the notion of being a public figure. Another of his projects for 2015 is a stage production entitled “The Big Girl.” Described as a reworking of Sophocles’ Antigone, the play will focus on the experience of a pregnant teenager who is the niece of a prominent Dublin TD.

Despite drawing on a sense of absurdity latent in the Civil War period, there were concerns over potential backlash amongst the committee prior to The Wind That Shakes the Party. Many of the props, including a selection of rare republican flags and a stone engraving of the proclamation, were purchased in the Sinn Féin store in Parnell Square. When asked by the shopkeeper why he was buying €120 worth of merchandise, Maurice replied that he was decorating his bedroom. Though the use of tact in certain situations may be warranted, the events themselves should be designed to provoke a response.

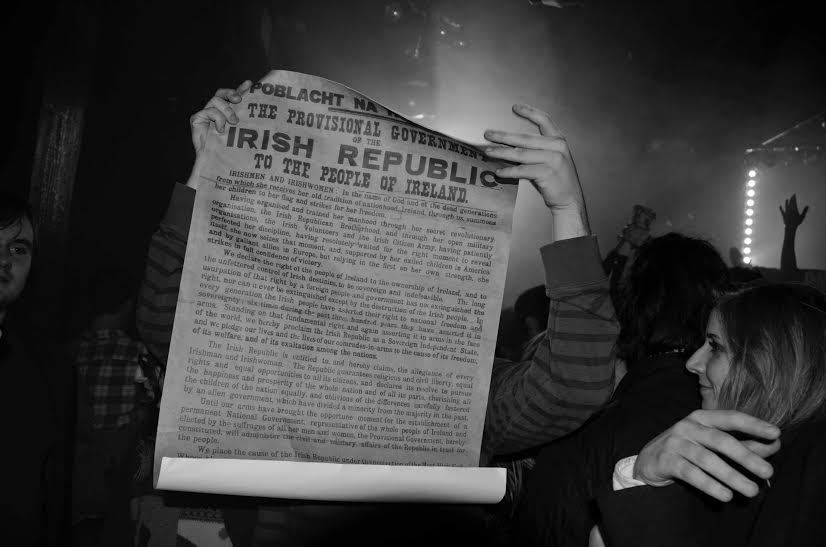

Maurice points to a particular anecdote in response to the same issue. During the course of The Wind that Shakes the Party committee members were forced to intervene when an overzealous patron set the Proclamation of the Irish Republic alight. It transpired he’d mistaken it for the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which had also been doing the rounds. “Even if you’re getting people involved by means of light arson its still encouraging historical awareness. Therefore Hungry, even if grossly offensive, will stimulate historical debate,” he states. At the very least, it seems the patron in question is unlikely to make the same mistake again. Finnán leans more toward the idea of accessibility as an intention behind events such as The Wall: “We’re well aware that everyone doesn’t love history quite as much as us, and might be less inclined to attend a lecture or talk on something like the Berlin Wall, but turning it into a club night makes it that bit more accessible. If people left the Wall with some bit more of an interest in what that night was based on then they had before then I think we did a good job.”

Finding new perspectives seems to be a common aim, between both events and perhaps Hungry as well. “I feel that the famine is as much the UK’s tragedy as it is Ireland’s and I would love to see it occupy a more public position in Britain,” says Finn. Maurice identifies the pervasion of false narratives particularly harmful: ” The horror of the famine is a central tenet in cultivating a sense of victimhood. The most visceral demonstration of this is the concept of ‘the undocumented Irish’. Where are the undocumented Mexicans or the undocumented Chinese? The concept is inherently racist, it states legalise us because we’re white and we speak English,” he states, in relation to Irish-American interpretations of the famine. “No element of the past should be sanctified. This is how grand narratives are constructed, there are more statues to the resistance in Austria than there were actual members.”

Maurice argues that people would do better to turn their attention to issues concerning the actual study of history, such as the demotion of the subject at Junior Cert level. It remains to be seen whether ‘Hungry’ will tackle the famine appropriately, or even make it on screen. However, it seems the controversy has touched upon something more profound. Articles published by sites such as Irish Central, demonstrate an inability to think historically, as evidenced by a recent article conflating nineteenth century caricatures of the Irish with Charlie Hebdo cartoons. There even seems to be a misunderstanding of the concept of comedy, as demonstrated by a frankly bizarre attempt at a spoof “leaked” ‘Hungry’ script. That their resonance is so widespread is disturbing.

As for Dublin’s only anti-Treaty club night, the evening came to a close with the committee leading their members in a round of the Lord’s prayer and the Angelus, before a brief rendition of An Dreoilín. Aside from the Treaty ports, who had resumed their argument in the queue for the cloakroom, it was clear from the dumbstruck silence that, despite the residual issue of national memory, DU History had thrown a party, and raised some serious questions concerning Post-Independence Ireland, that their members would not soon forget.

Photo of The Wind that Shakes the Party by DU History.