Every August, the delighted faces of many Leaving Certificate students are published online and in newspapers the length and breadth of the country. However, less noticeably, there are a sizeable proportion of students who are disappointed with results that are perhaps unexpected, or that don’t reflect their abilities or expectations. For these students, appealing their grades can be an option. It’s a prolonged process with little guarantee of success, however this did not discourage 5,000 students appealing over 9,000 grades this year.

Statistics

Two weeks after the release of Leaving Cert results in mid August, candidates can view their exam scripts in their school or examination centre in the company of their subject teacher. If the student feels it is the case that they were marked unfairly and not in keeping with the marking scheme, they may appeal their grade, at a cost of €40 per subject. This fee is refundable in the case of an upgrade, which is completed by mid-October.

This year, 9,809 grades were appealed by 5,660 candidates in an array of subjects. Consequently, 1,822 grades were increased following appeals, which amounts to a success rate of 18.6%. A further five results were downgraded. The State Examinations Commission (SEC) noted that the 1,822 upgrades accounted for only 0.47% of all grades awarded in the 2015 Leaving Cert.

Due to this subsequent increase in CAO points, in 2014, 380 college applicants were offered a place in the second week of October. In this case, you may accept the new offer or remain in your original course. However, in many cases, colleges request that the student defer until the following year due to limits on places or the amount of work missed, which could be up to six weeks in some colleges.

Candidates can view their remarked scripts in late October at the SEC offices in Athlone and apply for a further recheck.

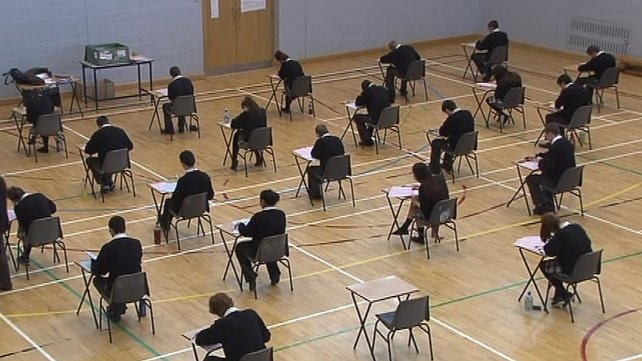

As with any large scale operation, errors occur. However, possibly the biggest flaw of the appeals process is the short timeframe between receiving results, appealing results and commencing college. This year the Leaving Certificate took place between June 3 and June 19. 2,000 examiners, selected from a pool of serving, retired and unemployed teachers, have 26 days to correct between 150 and 300 papers each, depending on experience. Marked scripts are then returned to the SEC by courier in mid-July, yet Leaving Cert results are released over three weeks later. This year, results day was August 12, while script viewing took place on the 28 and 29 of the same month.

Different approaches

Even in my own school, this timeframe was so tight that some students were moving to college straight after viewing their scripts. There is simply no need for this additional pressure and panic. In the UK and France, college offers are distributed during the previous academic year, which eliminates a proportion of the unknowing confusion about where your future lies if results don’t go your way.

The French Baccalaureate took place this year from June 17-24 and yet students received their results on July 7, less than two weeks later. 170,000 teachers correct between 70 to 150 papers in 10-15 days. There are options for student to repeat failed exams later in the summer, with French universities commencing in early September. In the UK, A Level results are released a day after Leaving Cert results, with universities starting in mid-September at the earliest.

The effects of entering the appeals process are somewhat undermined and forgotten. Emerging from the stress and difficulty of Leaving Cert results day, to be directly submerged again into the world of marking schemes, teachers and grades is overwhelming. This coupled with the intense uncertainty of your immediate future, whether you should start packing for college or finding your exam papers, is exasperating. For some those five extra points is the difference between careers, the difference between college or a Post-Leaving Certificate (PLC) course.

Personal Experience

I am a first year student fresh from the Leaving Cert appeals process. On Leaving Cert results day, I found myself disappointed with certain results in subjects that I had previously excelled at. In hindsight, I was probably unnecessarily upset over the debacle but I felt I had failed myself in what is billed as the most important exam of your life, the pinnacle of your secondary school career. I decided to recheck my French and music results and in the meantime commence my third choice course of History and Political science at Trinity. Six weeks passed and I received a phone call from my secondary school informing me that my results had increased by one grade in each subject, affording me 15 extra points. My initial feeling, surprisingly, was not delight but annoyance.

I was aggrieved by the incompetency of the SEC not just once, but twice. All the disappointment of results day could have been avoided and I should have been offered my first choice. The power and influence the SEC wielded over my future was very unsettling. Eventually, I decided not to take up the offer of my first choice due to numerous factors. However, if I had, because my first choice was also at Trinity, I would not have been anywhere near as inconvenienced as those who may have to change college, cities or even countries due to their upgrades. This causes completely unnecessary upheaval at such an unsettling period of our lives.

For Julie Farrell, a master’s student in Interactive Digital Media at Trinity, the process was considerably longer. A student of the 2011 Leaving Cert class, she viewed her biology script with her teacher, who felt there were grounds for a grade increase, and followed the appeals procedure. In the meantime, she commenced her fifth choice course, French and classics at Trinity. When appeals results were delivered, Julie found that she had not received the expected increase. She reviewed her script in Athlone and applied for a second recheck: “When it came back that I didn’t get the upgrade, I was really annoyed. It was just really intimidating for an 18-year-old to do.”

The upgraded result was returned to Julie via her school in January, over six months after sitting the Leaving Cert. “I was just really delighted that I had stuck to my guns. I think people can be really upset and vulnerable in that kind of situation. They think that they’re just grasping at straws but if you really think you should’ve gone up, I’d really recommend it to people, even just for your own piece of mind.” The increased points gave Julie the option of her fourth choice course, which she subsequently turned down. “For me, it was the difference between 495 and 500, which is nothing. For me, it was just in my head, to get the 500 and that was it.”

In the same way that there has been calls to reform the points system, the appeals process requires huge change also. The expansion of the time frame is key to allow student to make informed decisions about their futures. In the long run, reform of the points system to something resembling the UCAS or French processes would also simultaneously benefit students who are left to appeal grades. However, as is the case presently, it is simply unfair to add to the confusion and vulnerability of students at such a transformative period in their lives.