“SECRET – Nothing to see here?” The exhibition running in the Science Gallery cracks cryptography, spills secrets and examines enigmas. Why do humans like to keep and reveal secrets, who do we share them with and why are we attracted to finding out other people’s’ secrets?

Secrecy can be active, empowering and enjoyable. Secrets are things we reveal to trusted friends, keep from foes, protect from prying governments or destroy through whistleblowing. From encryption to PIN codes there are many ways to hide your classified information from prying eyes. Whether you’re a scientist or a spy, you approach the world with an outlook to uncover the secrets hidden in the world. Here is a selection of pieces that I saw when I visited the exhibition.

Walking into the exhibition, the first thing you notice is the queue of people waiting in line to get a picture wearing a relatively ordinary grey hoodie and accompanying grey scarf. But in fact these seemingly mundane objects are actually the ‘Flashback Photobomber Hoodie’ and ‘Flashback Silver Screen Scarf’ which are part of the ‘Flashback Collection’ by Chris Holmes and Betabrand. The clothing is made of a reflective material (glass nanospheres) that bounces the light from the flash of cameras and obscures and effectively ruins photographs. All that can be seen in the photograph is an ultrabright hoodie and scarf that dominate the picture and the person wearing it isn’t even a silhouette. A real life ghost creator without the need of any special effects. It might not seem like an object that most ordinary people would buy but it is definitely something celebrities would consider. Celebrities who are constantly hassled by paparazzi will now be able to wear clothing that makes paparazzi photos worthless or at least gain some valuable photographic anonymity.

After chatting for a while to one of the very welcoming and insightful mediators, who are dispersed around the gallery, I made my way over to the source of the jazz. The exhibit ‘AM Audio Desk Light’ by Steven Tevels, a project designed to transmit and receive sound through a modulated beam in a more secure way. Radio waves can be easily intercepted, but by deciding to use a LED light, Tevels has found a secure way to transmit data over a short distance without being intercepted, because data can be transmitted over a short distance without being intercepted. Initially it seemed odd to see a black desk lamp used in the setup for playing music, but in the setup the audio output of the iPod is connected to a flickering LED light which shines onto a photocell. The photocell generates electricity when the light falls on it, and the audio it receives is amplified by a connecting speaker. If secret data were contained within, then somebody across the room would not be able to intercept and read it, making it a very secure solution.

Another piece that grabbed my attention was the PIN machine at the top of the stairs that welcomes you as you enter the second half of the exhibit. A screen tells you how many times the PIN you enter has been entered since the opening of the exhibition. When I entered a PIN, I knew my PIN would not be unique. I typed it into the machine to see ‘[XXXX] – selected 6 times’ and I was not surprised. There are only 10,000 possible combinations for a code of 4 digits length which allows repeats and each character can only be a digit from 0 to 9. That slight feeling of vulnerability that the PIN machine created is then exacerbated by the exhibit ‘Forgot Your Password’ by Aram Bartholl. There are 8 alphabetically ordered volumes containing 4.7 million stolen passwords that were decrypted and posted online after Russian cyber criminals hacked into LinkedIn.com. The sheer number of passwords printed on two adjacent pages is mindboggling. As you search through the book to see if your password is there, you start to realise how ‘not so’ ingenious your password is. The “Forgot your password” section of the exhibition will make you feel like it may have well been “bananas123”. I breathed a sigh of relief to see my exact password wasn’t there, but there were too many alarmingly similar entries for comfort.

The next piece that really intrigued me was the “Transparency grenade” by Julian Oliver. It is certainly the most symbolic piece of this exhibition. Concerned with the lack of corporate and governmental transparency, the grenade is the iconic cure for these problems. Containing a tiny computer, microphone and powerful wireless antenna, it captures network traffic and audio at the site that the pin is pulled and securely and anonymously streams it to a dedicated external server where it is mined for information. As a final image of the show, it represents the power and destruction that can be unleashed when private information is disclosed. And like most wars these grenades will damage the civilians caught amidst the chaos, the public will be exposed more in the future as the amount of information on every one of us grows online, making it more susceptible to being revealed by hackers. There are many other brilliant parts to the exhibition that I haven’t touched upon but I would advise the reader to go explore. The Science Gallery is also running weekly workshops that explore different aspects of the theme of SECRET.

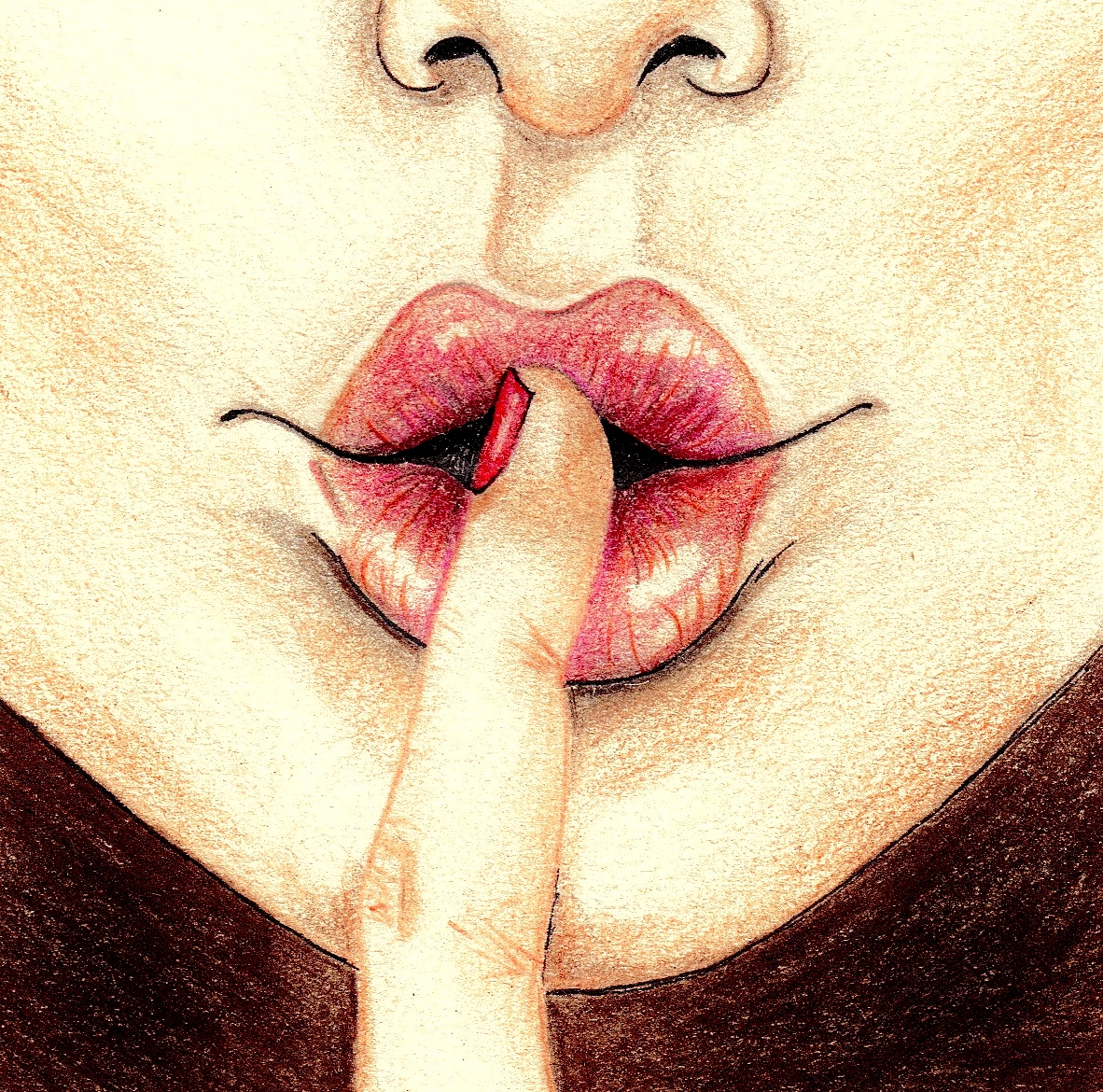

Illustration: Sarah Larragy