“More and more polls indicate that more and more people are saying we have to let it go”

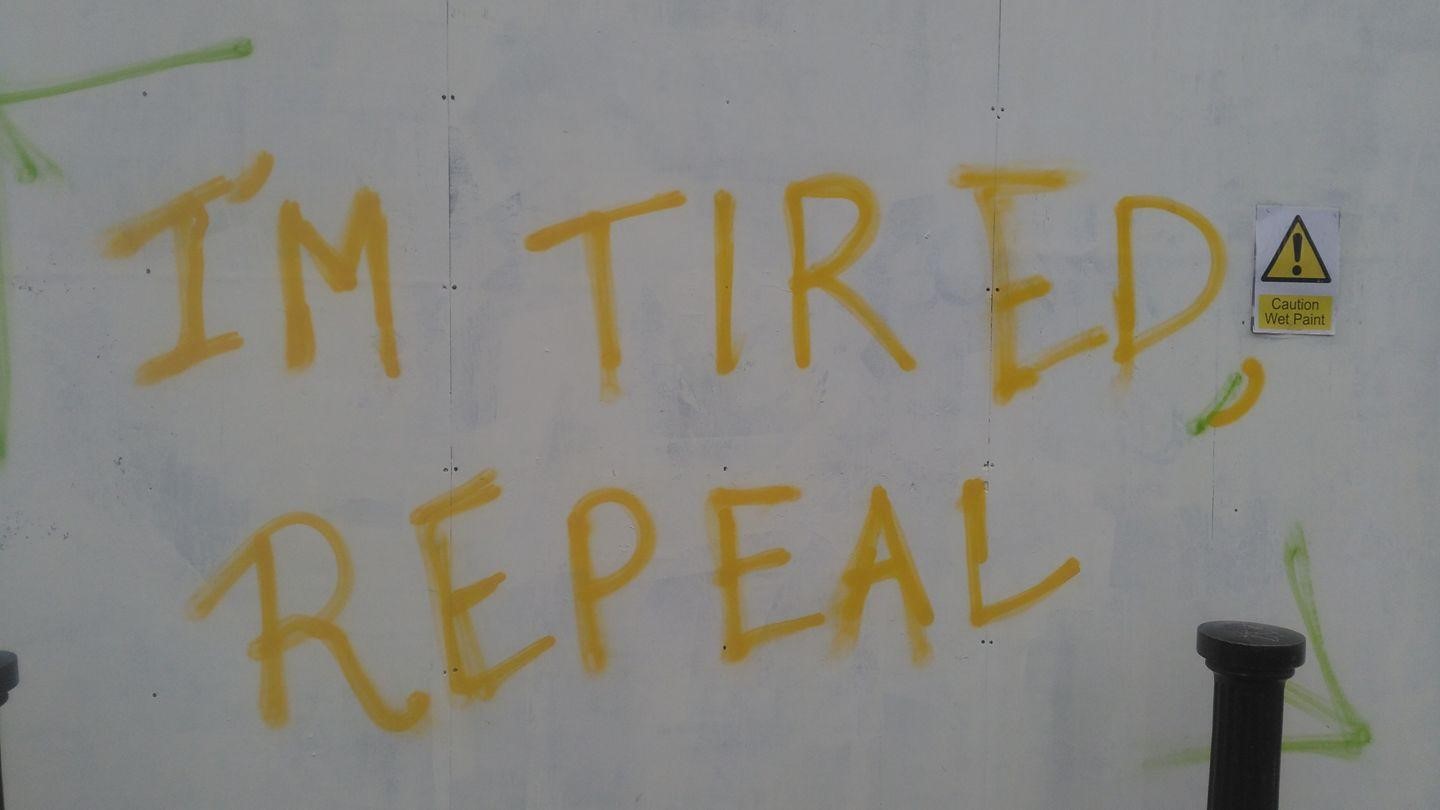

Construction on Pearse Street recently presented a new outlet for voices to be heard. White, blank construction walls lined the busy road, serving as a canvas for any who might avail of it. Options were plenty, from simple graffiti to street art, or more recently, political messages.

But what happens when these messages shift from political to violent? What happens to a movement when the desire for change sparks outbursts of anger, hatred, or violence? Is breaking the law a requisite of civil change, or does it just destabilise the whole foundation and justification of that cause?

In an effort to find out what drives these types of messages, I went looking for the perspectives of two polar opposites of the movement. Cora Sherlock, speaking at the Trinity Laurentian Society, provided an in-depth perspective into the Pro-Life movement, while TCD lecturer Jo Murphy-Lawless, a feminist who has been fighting the 8th Amendment since its implementation in 1983, spoke in support of the Pro-choice movement.

Both claim their ambition is to listen to women and to provide them with what they need. Both claim that they aim to establish basic human rights in Ireland. Both fervently fight for what they believe.

But is either side listening to the other? Is abortion a conversation, or a shouting match?

The History

“[It’s a] very safe kind of a discourse. The thing around home and family and so on, and who wouldn’t want that. But there are thousands of women who don’t have that”

According to Sherlock, the years have degraded Irish society’s ability to talk about abortion. When she was in college, she says there were “debates where you had much more discussion of ideas”. She argues this was healthier than today’s political climate, where even the state is funding the Pro-Choice message through organisations like the National Women’s Council.

Murphy-Lawless argues that this sense of polarisation has been engrained in the Irish debate from the beginning. “There’s just such a disturbing background of how we got into the 8th Amendment in the first place.”

In Ireland, there was little debate surrounding abortion. The Offences against the Person Act 1861 made it illegal to “procure her own miscarriage”, but there was no discussion as to what constituted life, and what did not.

She explains the US had a much more extensive history surrounding the argument, with legislation restricting abortion introduced to protect the rights of the physician as far back as the 1890s. As time went on, the moral rights of the foetus came into question, and a divide emerged.

By the 1980s, “Pro-Life” activists had begun to actively fight abortion, arguing that the life of the foetus equalled that of a person. This appealed to the Catholic rhetoric of many in Ireland, and was adopted in the form of the 8th Amendment in the 1980s. By adopting this American perspective, we too adopted the clear divide between “Pro-Life” and “Pro-Choice”.

Murphy empathises with the Pro-Life side, however, and attempts to explain what she thinks the Pro-Life mind-set is: “[It’s a] very safe kind of a discourse. The thing around home and family and so on, and who wouldn’t want that. But there are thousands of women who don’t have that.”

Particularly in an American context, the working class are increasingly forced to struggle for decreasing rewards. With little hope for improvement, Murphy-Lawless points that their children are their brightest hope for the future.

“I can’t do much for myself, but I am going to put my energy into that foetus having a right for life. That makes that foetus a much more significant part of a political feature. And it can tip over into violence.”

The Women

“There is a reluctance to listen to women who regret their abortion. You’re really only able to shout your abortion if it’s about how great it is”

“I feel very strongly because I don’t know what women need,” says Murphy-Lawless, “We need to ask them what they need.”

“I remember being in one very small town, not much bigger than a village and talking with a 22-year-old woman who had begun to have sex when she was 13. She was pregnant when she left school just under 15 and had no access to any forms of contraception or termination. The young lad who was involved with her couldn’t take that pressure, and walked off. We need to think a lot more about what we’re doing to women in that situation.”

It is judgement placed on women in this situation that can be so harmful, she argues: “She should be studying for her Junior Cert [people think], but it doesn’t work like that. All things sexual are part and parcel of everydayness, part of this new Neocapitalism. People make a hell of a lot of money, but it hasn’t been made safe.”

Listening too, is a central part of Sherlock’s philosophy. While feminists argue abortion is a form of liberation, Sherlock instead condemns it as another method of control. That if it were implemented family, partners and society would simply use it as a means of dictating what a woman should, or shouldn’t be.

“This “choice” is being exercised by women who don’t have money or don’t have a supportive partner,” Sherlock explains.

Her example of this is #ShoutYourAbortion. “There is a reluctance to listen to women who regret their abortion. You’re really only able to shout your abortion if it’s about how great it is”.

She claims that rather than support women and their children, it places all of the burden on the woman. Women who have publicly spoken out against abortion have been criticised and publicly attacked, according to Sherlock. Unwilling to listen to their perspective, these women are instead the victims of Twitter and Facebook slander. To her, this is indicative of the state of the debate as a whole.

“We gave you the right to choose, and you chose.”.

The Debate

“In outbursts of emotion like the graffiti above, what is achieved politically? At what stage should voices be lowered, and a discussion started?”

Sherlock insists that the Pro-Choice movement is concerned only with unrestricted abortions up to full term. A major concern for her is the use of limitations surrounding abortions as a wedge to achieve such unregulated access. “People who say they want it up to 12 weeks, really want it up to birth.”.

Another major criticism Sherlock has of the Pro-Choice campaign is the lack of acknowledgement of the male perspective. Pointing out the men grieve over abortions as well, she thinks it is necessary to bring both men and women into the debate and acknowledge both of their rights. “How do men take part in the debate? I think men are shut down.”

Blue “Male” Pro-Life pins and frequent mentions in her talks of male mourners speak of the desire in the Pro Life campaign to include men. Far removed from the Rachel Green “No uterus, no opinion” rhetoric of some Pro Choice campaigners, it could have an interesting influence on a debate where men represent half the voting demographic, and Sherlock recognises this fact.

While no referendum is in the immediate future, should it be put to the Irish people, and if so, what would be the result?

Sherlock insists that it would be irresponsible and ridiculous to have a referendum. Praising the foresight of those who implemented the original 8th Amendment, she argues that there would be no referendum that endangers the right to life. Furthermore, she argues the political climate at the moment makes a fair referendum impossible, citing examples such as the “Student Union taking a very unfortunate stance” when they should be “neutral on really controversial issues like this”.

“If abortion is a human right, then a child who survives an abortion is a living violation of a human right,” she half-jokes.

Murphy-Lawless, however, feels that a referendum is necessary in a country with quickly shifting political views: “More and more polls indicate that more and more people are saying we have to let it go. I’ve seen that shift among midwifery students in the last 10 years, who would’ve been a lot more hesitant. They’re not hesitant about it now.”

Having worked closely with people involved in high profile cases such as that of Savita Halappanavar (who died from sepsis in an Irish maternity hospital), Murphy-Lawless insists there has been a resurgence in emotion surrounding the topic: “I think it has galvanised people again.”

Speaking of the X-case, she talks of the outrage and disgust felt by the country at the time as well.“She was raped, you can’t hold her prisoner, what are you doing?” were the thoughts going through the public consciousness, she explains.

While the 1995 Divorce referendum passed by only a slim 9000 votes, Murphy-Lawless explains that this was due to the voting demographic in Ireland at the time. With emigration driving the majority of young people abroad, it was the conservative older generations that remained, who showed reluctance to move away from the traditional Catholic values.

This is no longer the case, however. “Formal restrictions for contraceptives were removed in 1992, and now there are ads on RTÉ.“

Ultimately, both women would like to see increased state care for women in crisis pregnancies. Summarising the over-simplistic polarisation of Pro-Life and Pro choice, Murphy-Lawless claims:

“Pro-Life, Pro-Choice, you’re making assumptions.”

In the words of Sherlock, “A lot of the debate has gotten so heated, that both sides are in agreement 100%, but it’s so polarised they don’t recognise it”.

Hearing the passionate way that Murphy-Lawless speaks about women’s issues, her determination to secure happy, fulfilled lives for all women is undeniable. Equally, Sherlock thoroughly articulated as a woman who was determined about achieving options for women. Neither are Anti-Life, nor Anti-Choice. And yet, this is what the debate so often implies. In outbursts of emotion like the graffiti above, what is achieved politically? At what stage should voices be lowered, and a discussion started?