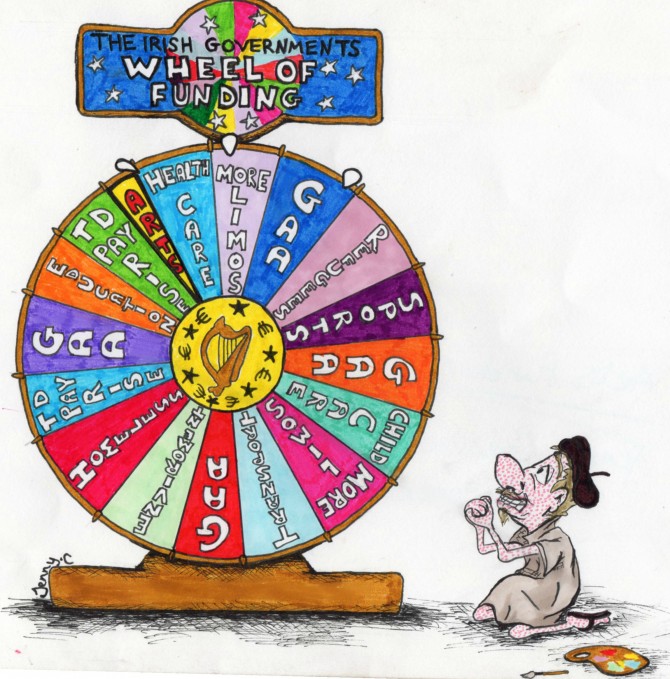

Last November, Taoiseach Enda Kenny admitted that the state has failed, repeatedly, to put arts and culture at the front of its public policy. Were the government to attempt to tackle this issue, it would be long overdue: arts funding currently sits at 0.1 per cent of the state’s GDP, languishing far behind the 0.6 per cent EU average.

Funding is always an issue when we talk about the arts, or culture in general. And where it comes from matters: private, public, philanthropic, fundraised, crowdsourced. Whether it’s the bake sales held by DU players to fund productions or PWC corporate sponsorship, each particular means of funding has its pros and cons. Crucially, however, state funding for the arts is vital because of its ability to secure financial stability and transcend the profit-motive; the perfect environment for creation.

Ethos informs art

“There is immense value to an ethos which promotes art for art’s sake”

There is a creeping trend of privatisation that is beginning to tread upon the arts; it should not be met with a shrug. Britain, for example, established a capitalist welfare state which promoted public provision of goods after World War II. In establishing this welfare state they also established the state funded British Broadcasting Corporation. However, the Conservative Party in the UK , who have already privatised public services such as the Royal Mail, have been corroding this market-provision and are working to outsource public services entirely to the free-market. They are currently conducting a review of the BBC; something which should not inspire optimism for the broadcaster’s future.

If we remove the state from the creation, broadcasting, and financial backing of art and culture we will lose a vital public service. The BBC is a unique service, much more so than RTÉ: the BBC is funded entirely by the state, whereas RTÉ features advertising; the BBC’s ethos is to enrich the lives of the British public. RTE provides news and entertainment in a way which is quite similar to a private channel like Sky, as they have to consider which programmes will bring in more advertising and sponsors. The BBC is something RTE should aspire to be.

“A State’s investment in art and culture makes art is a public service; a financially secure public initiative motivated by service instead of profit”

There is immense value to an ethos which promotes art for art’s sake while maintaining its public duty to educate and enrich society with stimulating and diverse programming for the entire public — not just those who can afford it. This combination of diverse aesthetic programming and purposively educative content cannot be replicated by private interests, who are concerned mainly with return, or those who must grapple for funding, whose projects will be modelled in a manner to be deemed financially and socially viable.

A State’s investment in art and culture makes art is a public service; a financially secure public initiative motivated by service instead of profit. A good example is BBC radio 4: funded completely by the taxpayer with no advertising. The perennially award-winning radio station — which features excellent cultural discourse and spoken word entertainment — is not at the mercy of private interests who will only fund or pay more for programming which reaches a mass audience. Obviously the BBC, as a public service, want as many people as possible to tune in to its broadcasts. But the power of catering to both the mass and the niche, to educate and stimulate, without the pressure of profit is of immense value to society.

Service dichotomy

Comparing the work of BBC 4 to Sky Arts is an interesting dichotomy. Sky Arts is an achievement in its own right; essentially the only televised channel fully devoted to the arts. While Sky Arts provides excellent tailored programming, its origin in the Murdoch empire limits the range it can offer its viewers. For every risky or niche area in which the channel invests, it must counter-invest in programming that will guarantee viewers and subsequent ad revenue. Otherwise a private enterprise such as Sky Arts isn’t a viable commercial venture.

On saturday at 9p.m, post reality show prime time, Sky Arts aired Discovering: Meatloaf. whereas BBC 4 aired Lost Kingdom of Central America which detailed the settlements of ancient Costa Rica. Of course while I’m not suggesting that a publicly funded broadcaster shouldn’t fund Meatloaf documentaries, I will leave you to decide which is more commercially viable. There used to be two channels: Sky Arts 1 and Sky Arts 2. Now there is just Sky Arts.

Philanthropy

“There’s one significant issue: often billionaires and millionaires are more likely to donate to “high-art” such as the opera or the ballet as opposed to youth theatres in rural Ireland”

Of course, the obvious argument against government funding of arts programming, or arts and cultural initiatives in general, is that the government has a finite amount of money which it can spend. Those who criticise the government funding of artistic and cultural initiatives, inist there are other other preferable routes.

This is way it is in America. In Britain there was a culture of collective public cultural provision linking back to medieval; in the US, museums were founded by wealthy families, whose descendants currently sit on the boards of the major art foundations. With low taxes and low public spending, philanthropy is a far greater giver to arts in the US than it is at home. But should we let the axe fall on the arts budget and promote this style of funding?

There’s one significant issue: often billionaires and millionaires are more likely to donate to “high-art” such as the opera or the ballet as opposed to youth theatres in rural Ireland. Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital helps to explain this phenomenon. Essentially, different genres of art have different cultural capital embodied within them which is associated with particular socio-economic groups.

Opera or classical music has cultural capital which is indicative of a higher socio-economic class. Whereas folk or rock music doesn’t and so it is less likely to be the benefactor of philanthropy. So often philanthropists will want to associate themselves with “high-art”. The problem here is there simply isn’t the analytical broad concern for all citizens and cultures which publicly-funded arts initiatives bring to the table.

Philanthropist Dame Vivien Duffield describes philanthropy as the icing on the cake, one that cannot properly exist without the base and security of government funding. Government funding leads a social example of what aspects of society deserve investment while Duffield also points out that, proportionally, “the poor give more than the rich”. She insists that if we relied solely on this method of philanthropy, it would leave us culturally poorer.

State funded art and culture initiatives enrich society in a way which other forms simply can’t. It’s easy, particularly during economic stagnation, to forget about the arts. But if don’t make our voices heard — we risk surrendering some of our greatest advances, cultural treasures we could never get back.

Sorcha Ní Cheallaigh contributed to this piece