The eve of St. Patrick’s Day saw Social Democrats Counsellor Gary Gannon launch the second issue of the international magazine, Trinity Frontier. In opening his address, Gannon joked about the great task ahead of him: a local politician, whose daily activities revolve around housing and potholes, asked to discuss the global issues facing us today. Having rejected the worn-out topics of the global working class and post-Trump predictions, Gannon settled on a timely issue, far closer to home, yet no less complex, asking “what does it mean to be Irish?”

Irish ministers travelled to the four corners of the globe for St. Patrick’s Day celebrations. At home, we wore green and drank Guinness; tens of thousands populated our airports and hotels in the hope of experiencing the craic and the céad míle fáilte. But what, we must ask, is the ‘Irishness’ we always celebrate?

An ‘Irish’ welcome

“we cannot today be silent and allow violations of human rights”

During our jovial celebration of national pride, revelations in the ongoing Tuam baby scandal, our worsening homelessness crisis, the daily exodus of women seeking bodily autonomy, and the Irish system of direct provision were whitewashed from existence.

While acknowledging the importance of rising up against racism, bigotry and misogyny, and asserting the need to celebrate Irish identity and culture, Gannon questioned what right we really have to criticise Trump, without first coming to terms with our own shortcomings – and how plausible our criticisms are without having actively worked through our own past and present.

Gannon’s question became more poignant when, hours later, our Taoiseach took the internet by storm, the Irish Times reporting in excess of 30 million views of Kenny’s St. Patrick’s Day address at the annual White House “shamrock ceremony”. The speech attracted international attention, with media outlets falling over themselves in praise of the Taoiseach’s “thinly veiled criticism” of Trump’s controversial immigration policies.

Direct provision

“Individuals in direct provision are subject to a curfew and set mealtimes, are forbidden to work or to cook for themselves, and are not entitled to third level education”

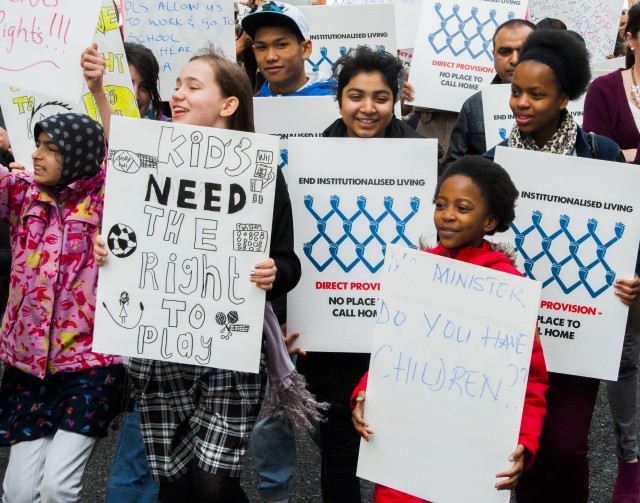

However, headlines such as “Irish PM SCHOOLS Trump: ‘St Patrick Was An Immigrant’ Right to Trump’s face!” and “Irish Premier Uses St Patrick’s Day Ritual to Lecture Trump on Immigration” suggest that neither the staff at Occupy Democrats nor the New York Times offices are familiar with direct provision, the system of detention subjected to all asylum seekers arriving in Ireland, which has been harshly criticised by both Amnesty International and the UN.

For a comprehensive and accessible overview of direct provision, I would recommend the Irish Times “Lives in Limbo” series. In brief, direct provision involves the detention of arriving asylum seekers in state-funded, privately-run centres throughout Ireland. Described as “prison-like” by grassroots organisation Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland (MASI), individuals in direct provision are subject to a curfew and set mealtimes, are forbidden to work or to cook for themselves, and are not entitled to third level education, training, language classes or social welfare beyond the allocated €19.10 per adult and €9.60 per child per week.

In Ireland, asylum seekers are so isolated socially, politically and economically, that former Supreme Court judge, Catherine McGuinness, claims a public apology for the damage caused by direct provision will be issued at some point in the future.

In light of the facts, Enda Kenny’s description of St. Patrick as “a symbol of, indeed the patron of, immigrants” at March’s ceremony rang hollow. Beyond securing the future of the undocumented Irish residing in the U.S., and taking a symbolic stance against Trump’s so-called “Muslim ban” and planned wall along the Mexican border, the Taoiseach’s rhetoric did little to clarify the Republic of Ireland’s position on those who approach our shores “deprived of liberty, deprived of opportunity, of safety, of even food itself”.

Scaremongering

“Irish society has developed a culture of victimhood, preventing us from adequately addressing our problematic history”

Kenny’s emotive statement that “[w]e came and became Americans” highlights the hypocrisy of Ireland’s 2004 citizenship referendum, in which 79% of Irish voters removed birthright citizenship from the constitution, restricting the capacity of people without Irish ancestry to “become” Irish. Through what Ronit Lentin, former head of Trinity’s Department of Sociology, characterised as a campaign of scaremongering, the referendum succeeded in privileging the rights of the grandchildren of Irish emigrants, who may have never set foot on Irish soil, over children born to non-citizen parents, who know only Ireland as their home.

It would appear that we are content to lament the horrendous experiences of those forced through poverty and famine to sail the Atlantic towards the “compassion of America”, but refuse to grant the same consideration, which allowed the Irish diaspora to thrive abroad, to those forced from their homeland today.

Academics suggest that Irish society has developed a culture of victimhood, preventing us from adequately addressing our problematic history. Indeed, we have failed as a nation to actively confront the horrors of industrial schools and mother and baby homes.

Our victim complex becomes clear when the fanfare of last year’s 1916 commemorative celebrations and the haunting Famine memorial on Custom House Quay are juxtaposed with the implicit expectation that those who have suffered at the hands of the state, and state-funded institutions, will accept their compensation and quietly move along. Perhaps we could learn from the German policy of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, a political, social and artistic movement, literally meaning “the overpowering of the past”.

Defeating the past

“Omission of responsibility and a culture of silence facilitated the widespread abuse of some of Ireland’s most vulnerable people while placed in the care of the Catholic church”

Vergangenheitsbewältigung has come to be culturally defined as coming to terms with a problematic past, with German society aiming to constantly acknowledge and re-work through the nation’s Nazi legacy by means of education, policy reform and commemorative action. If the Irish people are to truly come to terms with our past, we must first take back responsibility.

Our government must take back responsibility for Ireland’s asylum seekers from private corporations with vested interests, and we must take responsibility for our own ignorance by educating ourselves on not only the horrors of the past, but also those of the present. Omission of responsibility and a culture of silence facilitated the widespread abuse of some of Ireland’s most vulnerable people while placed in the care of the Catholic church; we cannot today be silent and allow violations of human rights at the hands of state-funded private bodies.

Although we are faced with great challenges, Gary Gannon’s closing remarks are worth remembering: “We are so close.” It cannot be denied that a movement is underway. People living in Ireland, particularly young people, are making their voices heard, and sparking debate on issues that are sure to shape our generation, and the generations to come. Let us commemorate those whom history has forgotten, vote on behalf of those who are denied representation, and acknowledge our responsibility in shaping both Irish identity and the legacy of our generation.