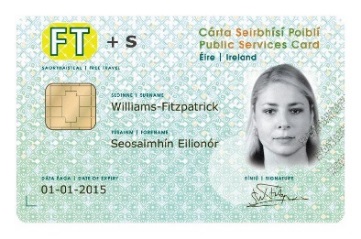

The card is designed to allow Irish citizens to access public services with an ease that is, supposedly, an improvement on previous systems. It involves a prior-authentication that eliminates the need for public services to attain your personal information; you simply present the card at any given point. Your information is encoded directly onto the card and, consequently, is shared immediately with over 50 state bodies, including the health service and the Gardaí.

The card is currently required for many state services already. It was first issued in 2011 to for collecting social welfare payments. Since then, its use has expanded to include driving theory test applications, first-time adult passport applications, passport replacements, citizenship applications, and access to government services such as social welfare and taxation.

The card acts in conjunction with the MyGovID website, an online portal through which public services are accessed. The aim of the PSC is to centralise a person’s information in one place and, in doing so, improve ease of access to public services. The claimed benefits of the card’s widespread use include increased efficiency for people who need access to these services, and an improved ability for the government to identify and eliminate fraud.

Many existing services will eventually require a card, including dental, aural and optical treatment benefits, all adult passport applications, applications for driving licenses, proof of age, student-grant applications, and the government’s upcoming online health portal.

Following an increased adoption of the card by the end of next year, it can be expected that further public services will be linked with the card and concomitant possession of it.

Currently, 3 million people have the card and 50 government bodies have access to the information stored on each PSC. Abuse of this database has already become a real concern; in late July, a member of the Gardaí came under investigation for the illegal abuse of private information, having accessed personal data without permission on the Garda PULSE database.

The question of whether the government is acting beyond its powers has been raised by, among others, Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald. Strictly speaking, the introduction of the card as a component of various public services is not outside the realms of the constitution. However, McDonald has made the point that the card can legally only be introduced as an option, not as the sole avenue to access.

By redesigning public services to be accessed only by the card, the government is taking a step outside the scope of its powers. There is no existing law that requires possession of a identity card before one can acquire a passport or a driver’s licence: that is, there is no requirement in law that should force Irish people to possess this card.

These rules that will affect the lives of Irish citizens are a result of administrative reconfigurations, a result of the government sidestepping its obligations to the constitution.

The PSC may be a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights, specifically of Article 8 which states that a public authority may not violate the private life of an individual except in cases of “national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others”.

By making the PSC a necessity for anyone desiring to access equally necessary public services, the government is inevitably accessing private information of an individual.

An argument has to be made against the card being rolled out in a forced way at all. The government is arguing for increased efficiency, but is efficiency worth a colossal security risk when it comes to information that is so important to the individual? Logically speaking, if a citizen has a birth certificate, a passport, and a PPS number, should they need anything else?

A total upheaval of established systems and a large gap placed in the defence of our private lives are unnecessary. If the government wishes to introduce the PSC as an alternative option to access certain services, then that is the state’s prerogative. However, depriving people of the choice to not get the card is wrong. Being strong-armed by the state to essentially surrender elements of our private lives falls into an uncomfortably shady realm.

On August 31, the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, stated that the PSC is not a national identity card and that the government has no plans to roll out a national ID card any time soon. On the surface, the PSC is less invasive than a national ID card. The latter can be asked for by police and army officials, requiring people to present it when asked to do so. The PSC does not empower state officials with this right.

However, the PSC is instrumental in the genesis of an “e-government” system that forces Irish citizens to possess this card. Such systems already exist to a certain degree: they are the means by which state bodies use information-technologies to interact with themselves and outside parties. The problem is that these outside parties are numerous and are not restricted. By putting such an e-government system in such an important position directly handling an individual’s highly sensitive personal information and by making this something that we have no choice over, the state is creating a gap in our personal defences.

The government has organised these developments so that the changes being made to public services are technically constitutional. But because the very ability to even leave the country is impossible without the card with its possession soon required to apply for a new passport, it becomes a necessity.

When this same requirement involves linking an individual’s private information with an insecure network of various governmental bodies, the card becomes a form of national ID card in all but name.

In April, the Irish Independent published a report on the record-breaking number of data-privacy complaints that were made to the Data Protection Commissioner in the last two years. The number of complaints has risen from 932 in 2015 to an all-time high of 1,479 this year. One of the chief causes of data violation according to the Data Protection Commissioner, Helen Dixon, is the leaking of various data from government bodies to private investigators. She described such instances of compromised data security as “ongoing”.

If there are such prominent leaks in Irish data security, how can the government in any way justify a scheme that will both centralise and expose the personal information of thousands of Irish citizens? They are demanding that people give up their information to a vulnerable system.

These life-changing series of plans are about to become a concrete reality. This change will completely alter the relationship between we, the people, and our government, when the extension Public Services Card starts to take effect.

The government is presenting the Irish people with a supposedly voluntary card that they cannot realistically avoid. This will not be the sort of “big thing” that happens to other people. It is going to happen to you, and to me, and soon.