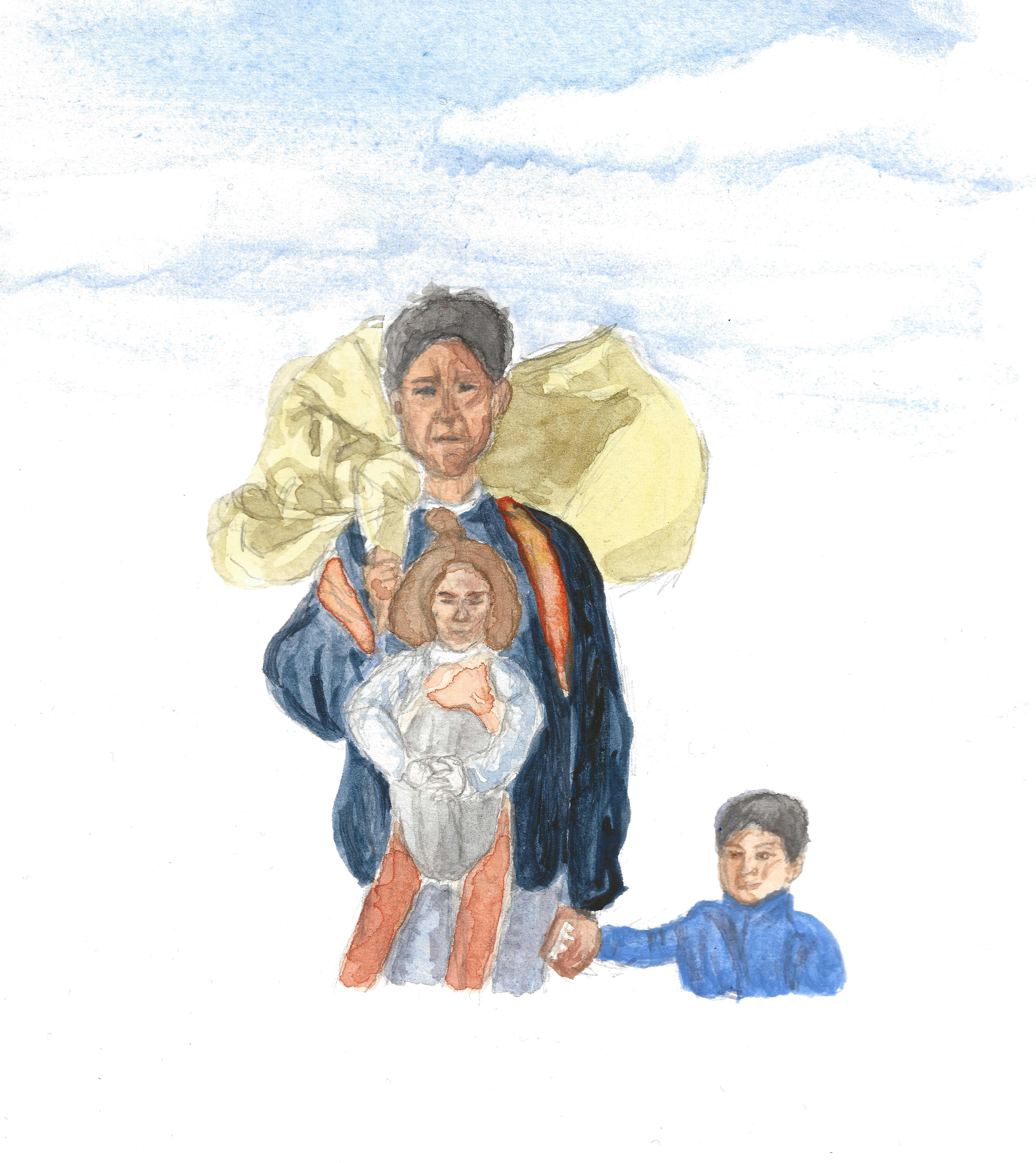

Summer of 2015 was when the refugee crisis peaked and first came to the attention of many Europeans. For the first time during the crisis, the media brought attention to images of refugees travelling across the sea and walking across the Balkans in a bid to obtain international protection. The images divided Europeans – some felt a moral obligation to welcome and protect, others saw no need. Many were shocked and appalled to see how refugees were treated by the Hungarian government. Towards the end of August 2015, we saw Angela Merkel make a landmark decision to open Germany’s border to all Syrian refugees. Just days later, the infamous photo of Alan Kurdi appeared online. Many who had not engaged with the crisis up to that point now became aware of the life-threatening dangers that came with entering “Fortress Europe”. Soon after, we heard of unacceptable numbers of migrant deaths in the Mediterranean, this time by those attempting to cross from Libya to Italy or Malta.

“If Europe allowed for safe passage through its borders for asylum seekers, then people would not have to put their lives at risks at sea.”

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) states that last year, 2,262 people drowned in the Mediterranean attempting to enter Europe – tens of thousands of distraught mothers, fathers, siblings, and friends. Trinity News spoke to Lucky Khambule, an activist with Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland (MASI), who campaigns for justice and dignity for asylum seekers. He argues that although we can attribute the crisis to political unrest in African and Asian countries, there is a much bigger issue at play: the state of Europe’s borders. If Europe allowed for safe passage through its borders for asylum seekers, then people would not have to put their lives at risks at sea.

Seán Binder, a Trinity graduate of PPES who has volunteered in Greece with a search-and-rescue NGO, has fallen victim to an alarming trend towards the criminalisation of humanitarian assistance. While volunteering, Binder and his colleagues were charged by police Greek police with a number of felonies, the most serious being “assisting aliens to enter Greece”. This happened despite the fact that the EU Facilitation Directive states that member states need not bring charges against people who do so “where the aim of the behaviour is to provide humanitarian assistance to the person concerned”. Binder believes that his case exists within a political sphere, saying “if humanitarian assistance is compassionate and if securitisation [of the border] is not, then the Facilitation Directive provides opportunity to allow for humanitarian responses to a crisis”. He refutes the argument that search-and-rescue NGOs act as a pull factor for people to risk their lives at sea. Binder refers to the critical fact that where search-and-rescue NGOs operate, fewer people drown. He and Khambule allude to the same argument that the current asylum policy, under which people must physically present themselves in Europe to claim asylum, leads them to risk their lives.

“A total of 792 refugees were relocated to Ireland under the programme.”

Despite the enormous human suffering caused by the refugee crisis, compassion is evidently lacking. The Dublin Regulation stipulates that asylum seekers must claim asylum in the first EU country they reach. Not only has this created a burden on Greece and Italy, but it also means that thousands of asylum seekers in those countries are competing for scant resources. The EU Relocation Programme aimed to move some asylum seekers in Italy and Greece to other European countries. A total of 792 refugees were relocated to Ireland under the programme. However, refugees who arrived in the EU after September 2017 are no longer eligible to avail of this.

The EU response thus far has been to increase funding on border security, invest in measures to discourage people from coming to Europe, and fund rescue operations in the Mediterranean. The Irish Naval service has been involved in such operations. Khambule argues that “there are countries, like Ireland, that want to be seen as doing something. You rescue a boat full of people selectively and leave some behind for dead.” Cathal Redmond, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice, told Trinity News that “Ireland takes part in Operation Sophia, an EU naval operation, that seeks to dismantle smuggling and trafficking rings”.

The EU has consistently failed to reach agreement on a plan to more evenly distribute refugees. There has been strong political opposition to migration in many EU states, undoubtedly intensified by the rise of far-right politics. Austria’s Freedom Party entered into a coalition government in 2017, after obtaining 26% of the vote in an election that saw the pro-refugee Green party lose all of their seats. Recent laws passed in Austria tie welfare allowances for refugees with German language acquisition. This could be viewed as an attempt to encourage integration or discourage potential asylum seekers. Germany has also seen a surge in support for the AfD, a far-right party. The Visegrád Group, consisting of Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland, boycotted an EU mini-summit on migration in June and have consistently opposed measures to redistribute migrants amongst EU states. Binder questions the far-right’s argument that they are protecting European values. He mentions the European value of protection is being ignored and argues that there is a huge difference between European conservative values and European values on the left.

“In a dangerous swing to the far-right, Europe is now using otherness as a justification to promote differential treatment.”

Attacks on Direct Provision institutions around the country evidence that we, in Ireland, are not immune to the rise of the far-right. In November, a hotel that was to be used as a Direct Provision centre in Donegal was deliberately set on fire. Khambule saw the attack as “a threat to peace in Ireland which is renowned for being a peaceful country”. Further threatening behaviour manifested in January, in another arson attack on a hotel earmarked as a direct provision centre on the Leitrim/Roscommon border.

In a dangerous swing to the far-right, Europe is now using otherness as a justification to promote differential treatment. Leading commentators in the academic sphere have advocated for a greater deal of societal concatenation for things to improve for refugees. The work of sociologist and political economist, Dr Stephen Castles, a research chair at the University of Sydney, has argued that the modern state’s model of inclusion leads to exclusion: “[The] nation-state has an inbuilt tendency to create difference and racialise minorities…Political and social measures are used to separate the other from the rest of society”. Castles insists that nationalism has allowed certain countries to lend themselves to the differentiation and racialisation of minorities. It could be argued that this is what Ireland’s asylum policy embodies. As awareness of the process of direct provision gains traction in Ireland, it is becoming more apparent that the system of segregating asylum seekers from the greater population both geographically and socially alienates asylum seekers. This also means that fewer people get opportunities to meet and interact with asylum seekers, a situation which lends itself to the perpetuation of stereotypes.

People have objected to the stunted autonomy of refugees entering this country. The Irish government is clearly in conflict with one of the main goals of the Global Compact for Migration. “To strive to create conducive conditions that enable all migrants to enrich our societies through their human, economic, and social capacities,” as the Compact outlines, does not include limiting rights to work and state-funded third level education. The Compact was signed by Ireland in December last year, but is not legally binding. “International protection claimants may access third level education on the same basis as any non-EEA third country national,” Redmond told Trinity News. “For international protection beneficiaries (i.e. those who claim have been recognised and have been granted a status), they can access third level education on the same basis as Irish nationals.” However, the financial barrier to paying non-EEA fees for those awaiting a decision on their asylum claim, which can take years, is not acknowledged here. As someone who has been through the asylum process in Ireland, Khambule has a differing opinion: “[Direct provision] promotes dependency and poverty. You cannot contribute to sustainable development in a country when you are stuck in direct provision, even if you try.” Despite recent restrictive rights to work for asylum seekers, Khambule insists that “the vast number of people are still stuck in limbo, we must not forget about them”.

An EU-wide programme to allow people to seek asylum at Europe’s embassies could help considerably to reduce the amount of people risking their lives at sea. Under the current system, people will continue to risk their lives to claim asylum, which is why the work being carried out by search-and-rescue NGOs is important. “Ireland is actively involved in the ongoing negotiations with our partners in the EU on reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS),” claims Redmond. “The reform of the CEAS looks at all aspects of international protection in the EU, including a revision of the Dublin Regulation. [We have] called for a speedy resolution to the negotiations, and [have] tried to reach a compromise across the divergent views of EU member states.” Ultimately, a change in policy direction that favours compassion is needed.

A greater effort in the way of inclusion is necessary in order to effectively incite change and truly help the cause of those seeking refuge in Ireland and in Europe. “[We must] stop treating asylum seekers as charity cases all the time,” Khambule insists. “Ask questions like, what can we do together? Not questions like, how can I help you? If we do that, we will make this country great together.” As Binder poignantly stated, and what cannot be denied: “There should never be a question on the left or the right [as to whether] people [should] be allowed to drown.”