Nursing and midwifery students face isolation from campus life throughout the academic year. The nursing building is located away from campus and all the main centres of student life, such as House 6 or the SU café, meaning even during lectures, the only part of the year structure wherein students aren’t doing 13 hour placement shifts, student nurses are still almost wholly omitted from student life. This contributes to high levels of student disengagement with clubs, societies and student publications, as nurses and midwives are not made to feel welcome in wider Trinity culture.

Student nurses on placement are expected to complete 31 hours of placement a week, often amounting to one or more 13 hour shifts within five days. This means the shifts expected of nursing students for the first three years, which are not paid, are beyond the guidelines of sociable hours, and so the limited number of students who do choose to participate in student activities are often forced to regularly miss out on meetups, rehearsals and training.

In addition to the workload faced by nursing students while on placement, their time is not always spent actively learning. Oftentimes students are given little productive work, especially for those doing specialised degrees such as intellectual disability nursing. An opposite extreme of this is students being asked to take on roles which extend beyond the Professional Code of Conduct for nurses and student nurses. The unmonitored delegation of tasks to student nurses is concerning, with students often being used as healthcare assistants (HCA) in short staffed facilities. Moreover, there is often no discipline for patients when they use racist slurs against student nurses carrying out their responsibilities – a common experience for both paid HCAs and students on placement. A standout example of the breaches of conduct experienced by student nurses is being asked to monitor patients who need to be “specialed”. “Specialing” is the monitoring of a patient by a qualified professional, but certain students have been left alone to perform this task – which is against professional practice regulations – as HCAs take breaks or work elsewhere.

“B&Bs and other forms of accommodation can be over €100 a week, which students must pay for themselves, despite placement being a mandatory part of their course.”

On top of serious breaches of professional conduct, nursing students are also subjected to financial exploitation. Dublin-based nursing students are often expected to do placements as far out as Kildare or Drogheda, and the travel and accommodation necessary for working in such locations is often not covered by the College’s inadequate reimbursement system. For students being placed in Kildare, for example, these reimbursements come in a few months later, upon the approval of kept receipts. The college will offer up to €50 a week for accommodation, which doesn’t adequately cover the expense. B&Bs and other forms of accommodation can be over €100 a week, which students must pay for themselves, despite placement being a mandatory part of their course and already being unpaid labour. Some accommodation providers in Kildare offer a student fee of €70 a week, which, despite costing students €20 extra per week of their own money, is still considered a good deal for this course-mandated accommodation.

The far-out location of these placements results in an added expense for any nursing student renting in Dublin. Students already subjected to the capital’s extortionate rental prices must then also find the money necessary to cover the extra cost of certain placement accommodations. This doubling up of rent, on top of an already unfair expense procedure, demonstrates a systemic neglect of the needs of nursing students, and a complete lack of consideration for those students who may already be struggling financially. The need to stay overnight at such locations makes it even more difficult for students to participate even in basic college activities. The process of moving out is often emotionally and physically draining, which can make placement much more of a negative experience for students, despite it being the part of their course that they’re meant to enjoy.

On top of this, fourth year internships are vastly inconsistent in terms of pay. Those working internships in hospitals during fourth year are not paid a standard rate; some students will receive the benefit of internships with better pay in privately run hospitals, while others struggle to make ends meet working with the HSE.

The experience of placement is intense and student complaints are often invalidated – they are told: “that’s the job.” In terms of college experiences, it rarely gets much worse than watching someone die. Critical incidents and a general sentiment of non-support by the College can lead to students even wanting to drop out. Student nurses are faced with the prospect of seeing death regularly on general placement and, while this is unfortunately to be expected while working in a hospital, no pastoral care or mental health support is offered in the event of a student witnessing a death. This factor is particularly important when considering the impact on first year students, who lack the desensitising experience of their elders.

The case can differ in private hospitals, however. Sometimes privately-run facilities offer support after a critical incident, such as through the form of a debrief led by a psychotherapist, but such responses are seldom found in the public sector. A massive disparity exists between placement in privately and publicly run hospitals, despite hospital selection being critical to students’ enjoyment of the degree and the level of active learning the student receives. The majority of the time, the functionality of the degree is left to luck of the draw.

Students have reported lecturers simply not showing up or being cancelled at the last minute. Moreover, for nursing students wishing to sit the Scholarship exams, placement has to be rearranged to be done in the summer.

For the rest of the academic year, time is spent in lectures. Unfortunately for nursing and midwifery students, this is similarly not a time always conducive to education. Students have reported lecturers simply not showing up or being cancelled at the last minute. Moreover, for nursing students wishing to sit the Scholarship exams, placement has to be rearranged to be done in the summer. This inconvenience often leads to nursing students deciding not to go through with exams and promotes a general discouragement of Schols in the community, further promulgating an existing disconnect between nursing students and otherwise typical aspects of student life in Trinity.

Students from across disciplines have expressed their irritation with the revised year structure and the ubiquitously poor implementation of the Trinity Education Project. Few, however, will experience a structural change to their years as dramatic as those in the Health Sciences. To begin with, the only reading week nursing students are given is during the Michaelmas term. The Hilary terms begins again after the winter holidays on January 6, and placement begins in early March. Students, therefore, will be either on placement or in lectures from January until the middle of June.

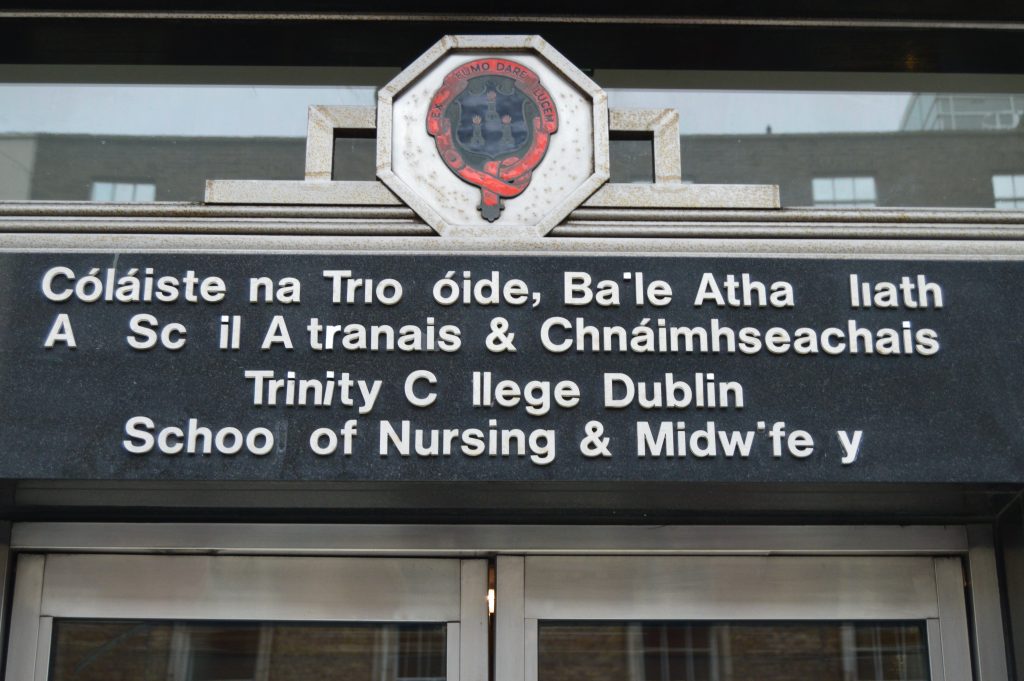

The single week off during this period is a revision week, which is dedicated to exam study as opposed to actual respite. Moreover, the nursing exams are segmented between two six-week stints of placement, which are both mentally and physically draining. The Health Sciences are ostracised from campus culturally and geographically (all their learning takes place in the building on D’Olier Street). This augmented experience of TEP serves as a single example of a wide-reaching problem, namely that these students are, and will continue to be, systematically excluded from the experiences of any other Trinity student.