Michael Collins remains a divisive figure in Ireland today. Widely known for his participation in the negotiations of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, bringing an end to the War of Independence, gave Ireland freedom — on the condition of partition and dominionship of the English Crown which led to a bloody Civil War. The hatred or admiration for Collins often comes down to family history, and the side on which one’s family fought in the civil war. As Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael entered into government together in 2020, many people are finally saying the Civil War is over, however bitter argument over the treaty continues and many families have not reconciled after they split following the establishment of An Saorstát Éireann and the beginning of the war.

From the time Michael Collins entered the Irish political scene until his untimely death, he made an enormous impact on Irish politics, being a key leader in the fight for independence. He used his immense political and military prowess to ensure that Ireland would be “a nation once again.” His actions along with that of Sinn Féin and the Republican movement succeeded in gaining independence and then managed to win a bloody civil war around the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Michael Collins was born in Cork in 1890 into a family of committed Republicans. His father was a Fenian, and the young Collins soaked up stories and songs of Irish Nationalism which planted his lifelong sense of patriotism. At the age of 16, following the civil service exam in Cork, he left Ireland to go to London and joined the Civil Service to end up working in London’s General Post Office. While in London, he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the Gaelic League, the GAA and was also sworn into the Irish Volunteers. He briefly studied Law at UCL before returning to Dublin in 1915. There, he learned not only about how a state is run but also he began to make his way up the ladder of the Republican movement.

Collins returned in 1915 and quickly established himself in the hierarchy of the IRB in Dublin, planning and preparing for the Rising with other members of the Kimmage Garrison. In Easter 1916, Collins served as Plunket’s aide-de-camp at the GPO. While he did not play a high-profile role, he nonetheless found himself in the heart of events, which he would later describe as “folly”. Following the end of the Rising, he was arrested and interned at Frongoch in Wales.

Following the execution of the Rising’s leaders, a power vacuum was left behind, and it was said Collins was already hatching plans before the prison ships left Dublin. His time imprisoned at Frongoch, which housed many of the interred soldiers of the 1916 Rising, had certainly the exact opposite effect than what the British had intended. Collins managed to establish himself as a leader amongst the men interned there and got to meet with other Republicans who believed that force was necessary to secure independence, which he became one of the foremost leaders within. While at Frongoch, he galvanised the prisoners for the battle ahead, hatching plans for the subsequent much more effective guerrilla war.

In early 1917 Kathleen Clarke (wife of Thomas Clarke) appointed Collins as the secretary for national aid, at the same time Collins became a leading figure along with Arthur Griffith in the Post-Rising movement. By October Collins was a member of the Sinn Féin Executive Committee. Following the 1918 Election Sinn Féin swept through Ireland claiming 73 of 101 Seats. Like the other newly elected Irish representatives, Collins refused to take their seats in the House of Commons, instead meeting in the Mansion House. At this time Eamon de Valera and a large amount of the leadership were arrested, before the meeting of the first Dáil, with Collins avoiding arrest. For a time, Collins hid amongst Dublin’s Jewish Community, once famously cursing at the Black and Tans in Yiddish.

Perhaps one of Collins’ first great actions was with the Department of Finance where he managed to put his Civil Service Experience to good use. He organised the National Loan. Managing to raise some £400,000 in vital funds which would be used to arm the IRA in readiness for the War of Independence, despite the British Government declaring it illegal. Money was held in the individual accounts of members of both Old Sinn Féin and the Old IRA. In 1919 Collins became the President of the IRB and director of Intelligence for the IRA which following the Soloheadbeg Ambush, now had a mandate to pursue an armed struggle.

During this time Collins (now also Adjutant General of the Irish Volunteers) spent large amounts of time reforming and organising the Volunteers to become an effective fighting force, sourcing material by ambushing and seizing Royal Irish Constabulary (the British police in Ireland) barracks. Michael Collins’ most critical decision was made here. In his commitment to avoid major damage to civilian lives and infrastructure. He decided to continue the campaign through guerrilla warfare. Which proved highly effective. Having learned from the mistake during the failed Rising this new strategy would see Flying Columns of Volunteers launch lighting and surprise attacks and ambushes before dispersing into the local villages and countryside undetected with no uniform or signifier for the British to target.

Through his leadership Collins managed to bring the British establishment in Ireland to its knees through an effective guerrilla force and an even more effective Intelligence Corps. He managed to cause the British to offer £10,000 for information leading to his arrest, while yet never being captured. Collins was the leader of the Squad, a group of 12 assassins who were highly intelligent in harnessing the information laid bare by a network of spies and informers throughout the city, and were successful in assassinating high-profile members of the British establishment in Dublin Castle.

It is clear the contribution Collins offered was unmatched; with de Valera in America for most of the war, Collins was the de facto leader of the country, later described as “the man who won the war “ by Arthur Griffith. By the time of the truce in 1921, the stones were laid for major operations which would’ve changed the tide of the war even more in favour of the Irish side.

Following the truce in July, a delegation led by a reluctant Collins, was sent to London, against the Empire. The Irish delegation negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which granted Ireland dominion status under the Statute of Westminster, under the threat of an “immediate and terrible war” from Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The key point of contention being the oath to the crown. Upon this news, Ireland was immediately split over the treaty, with the Dáil voting 64 – 57 in favour of the treaty. Prophetically on signing the monumental treaty Collins declared to Lord Birkenhead in 10 Downing St. that “I’ve signed my own death warrant” — indeed, he would be dead within a year.

Collins saw the treaty as a means to an end; while the republic would not be achieved and the island instead being partitioned, dominion status gave Ireland the “freedom to achieve freedom.” He understood immediately the consequences of his decision and that a large part of the Irish population would not accept the terms of the Anglo-Irish treaty. Perhaps war with Britain had been avoided but Civil War in Ireland seemed inevitable. While many realised the pragmatism of the treaty, many could not accept any connection to the British Crown whatsoever.

Following this, Sinn Féin split with Michael Collins leading the pro-treaty faction and de Valera leading the anti-treaty side, this was followed by a split within the IRA. In fact, all of the country was divided, brother against brother, mother against son, neighbour against neighbour, the division was felt everywhere. The country was sliding inevitably and tragically towards turning on itself. With Collins also acting as Commander-in-Chief of the IRA, this set the stage for a bloody civil war.

During the war, Collins not only had a large impact as the Commander of the Free State Army, but he was also running a new fledgling nation. While trying to turn the guerrilla force of the IRA into a traditional uniformed army was undoubtedly a massive challenge. This came to a point during the Battle of Dublin which saw this army actively in combat against the very soldiers who fought with Collins not a year earlier, notably at the Four Courts.

In a move for peace, Collins returned to Cork, where talks between pro-treaty and anti-treaty forces took place. To stop the fighting, it was proposed that the leadership of the sides meet. Famously, this did not happen. Despite it reportedly being overheard saying “Yerra they won’t kill me in my own county” Collins was shot whilst on tour around Cork. He died on the 22nd of August 1922 when an ambush was laid by Anti-Treaty Irregulars at Beál na Bláth.

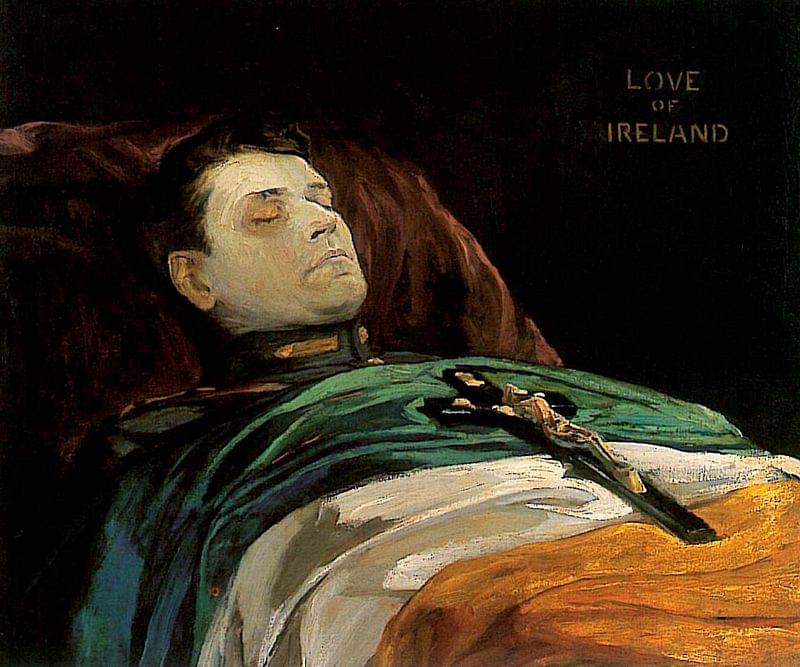

General Michael Collins was dead. The nation was left reeling. His subsequent funeral was a national event, the likes of which Ireland had never seen, following an open viewing of his remains in City Hall, he was carried to his final resting place in the Patriots Plot of Glasnevin Cemetery. To this day, his grave is the most visited in the entirety of Glasnevin cemetery.

Despite his untimely death at the height of the Civil War, Collins through his combined political and military leadership had a major impact on Irish Affairs, especially through his actions as Commander-in-Chief of the National Army and as Minister for Finance. From his time in Frongoch to his death at Beál na Bláth, he managed to form a large part of the national psyche and his actions have led to a major political divide in Ireland which ended in 2020 with the formation of the Coalition Government between Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. The enormity of his contribution to Irish affairs is unmatched. With the recent centenary of Michael Collins’ death, and Civil War Politics finally coming to a close, we can now truly reflect on Collins and his role in the formation of the Irish State. The treaty remains ever so controversial and still causes arguments in classrooms and kitchens across the nation and amongst our global diaspora. Ireland has become one of the most prosperous countries in the world. While of course we are far from perfect, with many issues regarding housing, healthcare and the environment, yet to be solved. However, our ability to have built a nation that is more than a Land of Saints and Scholars, but also an Isle of Innovators. Coming from the political groundwork laid down by both sides of the conflict, Collins and DeValera both have a huge impact on our lives today, and as portraits of the Big Fella and Dev hang proudly in the Taoiseach’s Office. I hope that we can no longer be divided and we can work together to build the “Ireland that we dreamed of.”