It was a big thing when Stephen Byrne died. He told the staff at Beaumont Hospital he wanted to kill himself. He had attempted to two days prior. They offered to send his file to his clinic in Ballymun. It didn’t offer much consolation and he died by suicide four days later. Regrettably the story is not uncommon. When Caoilte O Broin died by suicide, after his family had attempted to engage with his psychiatrist, it was a big thing.

Caoilte faced difficulty getting treatment as he suffered both from substance abuse and a mental health problem, known as dual diagnosis. He was turned away from some services; his family say “nothing could be done to help Caoilte, because he drank heavily”. Dual Diagnosis Ireland hope to highlight “the lack of services” and to advocate for sufferers to “get the right kind of treatment at the first time of asking”, for them Caoilte’s experience was not a once off.

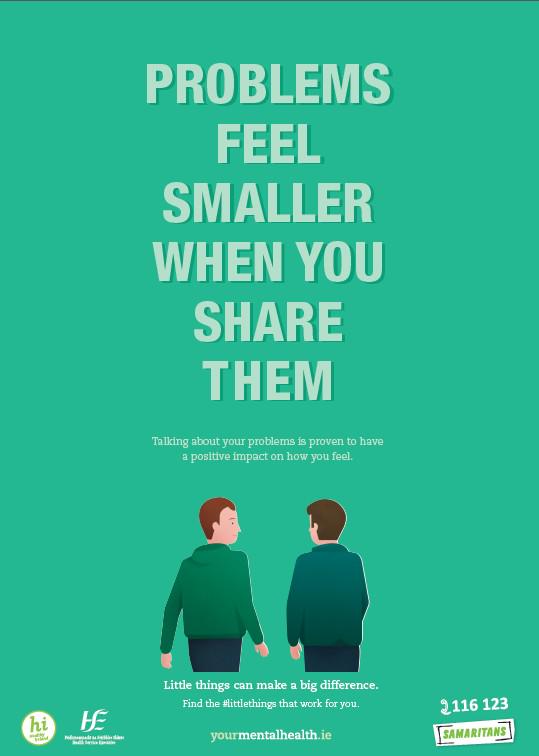

The National Office for Suicide Prevention was set up in 2005 to “to oversee the implementation, monitoring and coordination of Reach Out, the first national suicide prevention strategy”. In October 2014, in conjunction with The Health Service Executive (HSE) they released the #LittleThings campaign. Posters could be seen in Pearse Street Station and on the sides of Dublin Buses, adverts are shown on national television and banner ads are visible on the side of your email account.

It was hoped that little things will improve mental health and presumably (as the campaign originates from the National Office for Suicide Prevention) lower Ireland’s high rate of suicide. The Central Statistics Office reported there were 459 suicides in 2014. That is more than double the number of people (196) who in 2014, died on Irish roads.

The nine adverts encourage viewers to sleep eight hours, eat healthy food, keep up with a “friend [that] seems distant”, drink less, listen to your friends, “add friends to your tea”, share feelings with friends, do things in a group and exercise. None of this information is new to someone experiencing troubles with their mental health.

A common problem sufferers encounter is their illness being dismissed as temporary and easily fixed. All that is needed is to take a walk or to eat more healthily. A campaign which perpetuates the idea that mental illness can be made better by little things promulgates the dismissal of mental health problems as trivial and passable with a “little” effort on the part of the sufferer. Presumably the rationale of any campaign encouraging action against stigma relating to mental illness, is that mental illness is like any other illness. Yet any other illness would not have an advert stating that a small action would have be “proven to have a positive impact on how you feel”.

Lack of solutions

The campaign places the onus on the unwell individual. Achieve mental wellness by taking the recommended steps. Become better without government assistance. Reliance on a peer group is a heavy feature; nowhere is it suggested that professional help may contribute to mental health recovery. Perhaps the HSE are aware of the waitlist and know that if an unwell person reaches out for help, they may have to wait nine months for an appointment. Certainly in England people are dying while they wait. What the campaign does not seem to be cognisant of is that people with mental illnesses can sleep eight hours, eat well, exercise have friends for tea and still be mentally ill.

It is deeply patronising to be someone in the depths of psychosis, mania or depression and see a sign telling you that simple steps make a big difference in your health. It is particularly patronising and upsetting to see a sign telling you to talk to a friend if you have already done so and the friend’s advice is to seek professional help on which you have been waiting six months. It is patronising to the family of one of 14 mentally unwell prisoners waiting for an inpatient treatment in 2014. Nor is a poster likely to be of assistance to someone forced to leave inpatient treatment after six months over two years, as their insurance cover does not cover any more.

Politicians profess to support mental health. The Green Ribbon is worn throughout May and was launched by Minister Simon Coveney. A marketing campaign is easier to show a commitment to mental health improvement compared to the alternative of funding accessible community mental services. It makes sense that there would be a government initiative to ensure a conversation about mental health goes on. It was left to various non-governmental organisations, such a Head Strong, Grow, Walk In My Shoes, Suicide or Survive, Spun Out and See Change to spearhead. It is important to talk about mental health, but we let suffers down when there isn’t the support to materially better their condition. Of all the above charities only Suicide or Survive hopes to “fill gaps in current service provision” and Walk In My Shoes seeks to raise their own funds, as a goal.

Charitable organisation, Genio works “to bring Government and philanthropic funders together to develop better ways to support disadvantaged people to live full lives in their communities”. They developed a multidisciplinary care team, based in communities for at risk people. Results have been positive, with “570 families throughout the country are benefiting from 30 community-based” services. The same model is used by St Patrick’s Mental Health Hospital; however, the option is only open to those who can afford high quality health insurance or roughly €100 per session with a psychiatrist.

Clearly money has been spent somewhere. The campaign shows an understanding of hashtags. The television advert slogan tells us “it’s the little things” but the print campaign opts for #LittleThings, as to add the grammatically correct “it’s” would break up the hashtag. It would be easier if it were the little things, but for people with mental health problems the campaign is of no consolation.