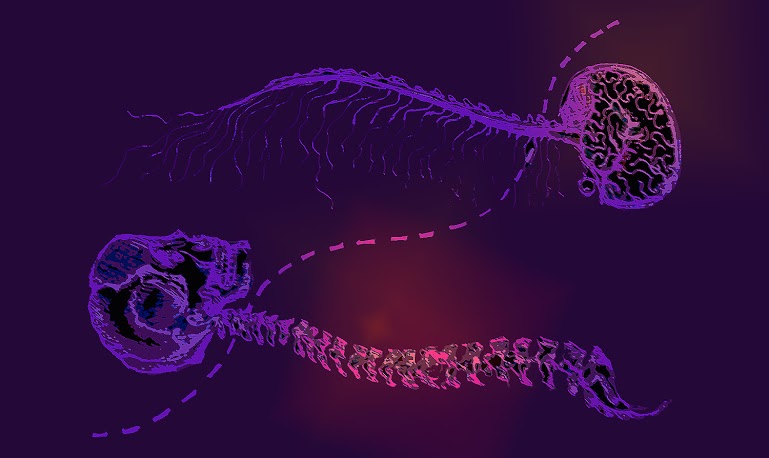

Head transplantation involves decapitating the patient and then grafting the patient’s head onto a donor body. Although it has been performed using dogs, monkeys and rats, results have not been universally successful and no human is yet to undergo the procedure.

Back in 1970, American Neurosurgeon Dr Robert White gained notoriety for carrying out the first head-body transplantation on monkeys. Despite being paralysed from the neck down, the monkey was able to hear, smell, taste and move its eyes. However, the animal died nine days after surgery because its immune system rejected the foreign head. Dr. Canavero attributes that failure to the technological inability of the time to rejoin the severed spinal cord. However, in a paper he published in the journal Surgical Neurological International entitled “HEAVEN: The HEad Anastomosis VENture project” he claims it is now possible.

Spinal cord reattachment

What Canavero’s theory entails is the use of a “specially fashioned diamond microtomic snare blade” which will sever the cord between the C5 and C6 vertebrae and release less than ten Newtons of force in the process. The idea of cutting the spinal cord sharply as opposed to bluntly does have a little medical support as the only example of successful spinal cord surgery comes from a case of where a man had a stab injury rather than a blunt injury to the cord. Canavero compares the spinal system and brain to an orchestra. The spinal system (responsible for making us move) playing the part of the orchestra and the brain the part of the conductor, directing the system. This accessible way to think about the relationship lets us know that the spinal cord is ‘no slave’ to the brain, according to Canavero the orchestra can still play without the conductor, albeit not as flawlessly.

The procedure

The surgery is estimated to cost over €10 million and will be a marathon procedure up to 72 hours long requiring 150 medics.

First both the bodies of the patient and donor will be cooled down to a temperature of around ten degrees celsius to extend the period in which the cells can survive without oxygen. The patient’s neck will then be partially cut and the blood vessels will be connected to the neck of the other. Then the spinal cord is cut, head moved onto the donor’s body and the spinal cord is fused together using a substance called Polyethylene glycol (PEG), which works like a glue, growing the spinal cord between the head and the body. The next step is the putting together of muscles and blood vessels.

The patient will then be put in a coma for four weeks while the head and body heal together. In a TED talk in Limassol, Canavero outlined his vision of the patient reawakening from the coma. Speaking with supreme confidence that he expects patients will report full near-death experiences, “after waking the patient will require extensive psychological counselling to deal with identity issues that will result from having a new body.” But he claims he will enable “quadriplegic patients to recover movements in full within one year.” On waking they should be able to move, feel their face and even speak with the same voice.

The head donor

Dr Canavero has found a patient who volunteered for the surgery. Russian computer scientist Valery Spiridinov who suffers from Werdnig Hoffman’s disease, a genetic muscle wasting, has proposed himself as a volunteer despite knowing the enormous risks involved. He says he “can hardly control his body now”, and that he hopes “in the future this surgery will help thousands of people who are in an even more deplorable state” than him. While many observers have expressed concern for Valery’s well being, others are happy to see that he is a willing subject.

The medical and ethical issues

Canavero has attracted a lot of attention, with public and professional opinion over his plans mainly being negative due to ethical and scientific reasons. Experts in the field state that the technology and timeframe in which he grounds his belief are unrealistic. Even if the patient did survive doctors argue there is little chance they would be able to move. Richard Bodgers, Director of the Centre for Paralysis research at Purdue University believes, “There is no evidence that the connectivity of cord and brain would lead to useful sentient or motor function following head transplantation.” Other members of the scientific community have reacted to his plans with a mixture of scepticism and horror. Arthur Calpan, director of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Centre, has described Dr Canavero as “nuts”, and believes the transplant is scientifically impossible and that Canavero has simplified the difficulties involved in reattaching the spinal cord.

From moral and ethical stance, public opinion would also seem to be against him. He has been publicly criticised by at least one international church and the Italian medical establishment, his home country has turned against him. An ethical predicament is that doctors may be motivated to perform head switching operations for all the wrong reasons. Dr Christopher Scott, a bioethicist and regenerative medicine expert at Stanford, worries “You’d have to make sure the motivations are around a true medical need, and not some desire to be famous.” He adds “These questions have been raised before, in procedures like face transplants.” But in fact Canavero assures us this is not the case and that this surgery could benefit those whose bodies have multiple cancers such as ALS. He justifies his ethical reasoning by saying that, “it is equally clear that horrible conditions without a hint of hope of improvement cannot be relegated to the dark corner of medicine.”

The outcomes of the surgery

The ultimate goal for the controversial neurosurgeon is immortality. He is convinced that his surgery will perfect and accelerate cloning with patients receiving a new young body to which their ageing head will be attached. According to Canavero “personality is in your old head and patients will get a boost of another 40 years” after completing surgery. As he delivers his futuristic message to “imagine a world where life extension becomes the norm”, one is reminded of the neo-noir film “Blade Runner”, incidentally set in 2019, where advertisements offer “custom tailored, genetically engineered humanoid replicants, designed especially for your needs.” Perhaps Canavero is making a claim straight out of science of fiction, or just running two years ahead of Ridley Scott’s schedule.

Illustration by Natalia Duda