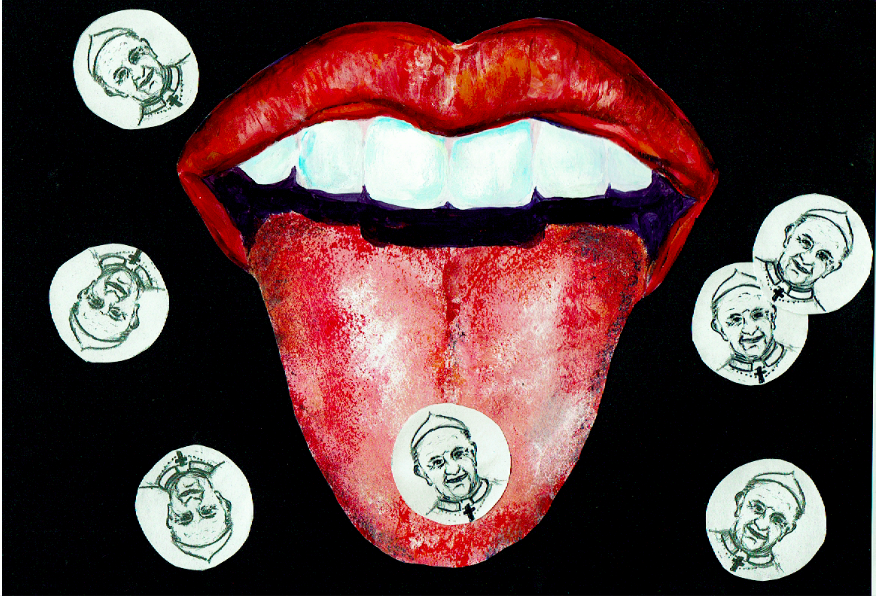

In January of this year, scientists have concluded that there is no health benefit to the customary seven day hormone-free break in combined hormonal contraceptives. Traditionally the oral contraceptive, known as the pill, has been prescribed with twenty one active pills and either seven sugar pills, or the advice to restart the medication after a seven day break. The new guidelines were issued by the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH), who set the British national guidelines for the safe prescription of contraceptives, and has since been confirmed by the HSE. This revelation swept through the press with considerable public backlash, particularly after the unfounded break was linked to appeasing the Catholic Church. Indeed the Telegraph published an article proclaiming the end of the “Pope Rule”. The fact that the seven day break has no scientific merit was monumental enough, but the additional blame on the Catholic Church heightened the public’s attention.

John Guillebaud, a professor of Family Planning and Reproductive Health at University College London, has been credited with identifying how the Pope is implicated. He reports that the break was introduced by the gynaecologist and devout Catholic, John Rock, in hopes that the Pope would accept the pill as it mimicked the natural cycle.

“He reports that the break was introduced by the gynaecologist and devout Catholic, John Rock, in hopes that the Pope would accept the pill as it mimicked the natural cycle.”

As we now know, this wasn’t enough to sway the stance of the Catholic Church, which still deemed the medication unnatural. There is an important distinction in the bleeding women experience in a break week and natural menstruation. The pill hinders ovulation, and so there is no egg or significant thickening of the womb lining that constitutes regular menstruation. Bleeding on the break week should be much lighter than menstruation due to this.

However, in the introduction of the pill around 60 years ago, this period-like week may also have been an attempt to reassure women they were not pregnant, and to instil trust in the newly-conceived birth control. Jane Dickson, the UK Vice President of the FSRH, was quick to establish this as one of the many reasons for the original inclusion of the break week when she spoke to VICE UK last month. In her opening statement, she rebuked the idea that the break week was solely due to Catholicism, and criticised the sensationalism of this idea in the press. She also emphasised the differences in the pharmacology of the pill we know today and the pill that would have been prescribed 60 years ago. The original contraceptive pill had 100 times the current dosage of some hormones in it. This physiological insult often meant that the women would feel unwell on the contraception and benefitted from a break.

The inclusion of the seven day break may actually be compromising the efficacy of the contraception. Guillebaud highlights this in a publication from 2017, entitled A Brief Update on Contraception, where he cites research showing that 23% of women developed pre-ovulatory follicles by the seventh day of the break week. He stresses that this is with “perfect use”. If a pill is missed around the break week, which can easily happen if the woman is late in restarting the medication, there is an increased risk of ovulation. Guillebaud highlights that this is regarded as “typical” usage, which has a contraceptive failure rate of 9%. For this reason it is suggested that if a women wishes to have a pill-free interval, she should consider limiting it to four days. The abolishment of the break week offers welcome support to women who suffer with painful periods, anaemia, and endometriosis in managing their conditions. In his conclusion, Guillebaud adds that millions of women have been “kept in the dark” that this is an option. He concludes that “menstrual bleeding (whether as a normal period or as a scheduled pill-withdrawal bleed) – and the nuisance and expense of any form of menstrual protection – is, in reality, optional”.

“Dickson hopes that the new recommendations will…will empower women to make informed choices on their healthcare.”

The only caveat is the possibility of breakthrough bleeding, however apart from this, there is no increased risk in continually taking the pill. Through rigorous testing, the break week has been shown to have no benefit. There is no need to “give the body a break” as so many of us have been brought up believing. Having said that however, the Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA) fact sheet still describes the combined pill in the following line: “The combined pill involves taking a pill every day. Each month you take a break for one week so you can have a period like normal.”

Although the Times Ireland reported that both the IFPA and HSE have dismissed the need for a break week as a “misconception” in light of the review, their online resources do not reflect this as of yet.

Dickson hopes that the new recommendations will challenge the held belief that you have to have a period, and will empower women to make informed choices on their healthcare. However, she highlights that this guidance is aimed at healthcare professionals. It is now their duty to provide this information in contraceptive consultations; women should always consult their doctor before making any changes. While we can appreciate the new clarity in these guidelines, the fact remains that doctors had been prescribing this medication to women on the basis of no scientific merit for decades, and in a fashion that is less than optimal for the intended purpose. This raises the question: are there any other skeletons in the closet of women’s medicine?