Many of his own people call Alexander Lukashenko “the Cockroach”. Foreign media outlets frequently refer to him as “Europe’s last dictator”. He freely admits to having “an authoritarian style of rule” and until this year, he was the only person to hold the office of President of the Republic of Belarus since the country’s independence from the Soviet Union. But that may soon change. His grip on power, seemingly unbreakable for the last 26 years, is suddenly slipping in the face of unprecedented popular resistance.

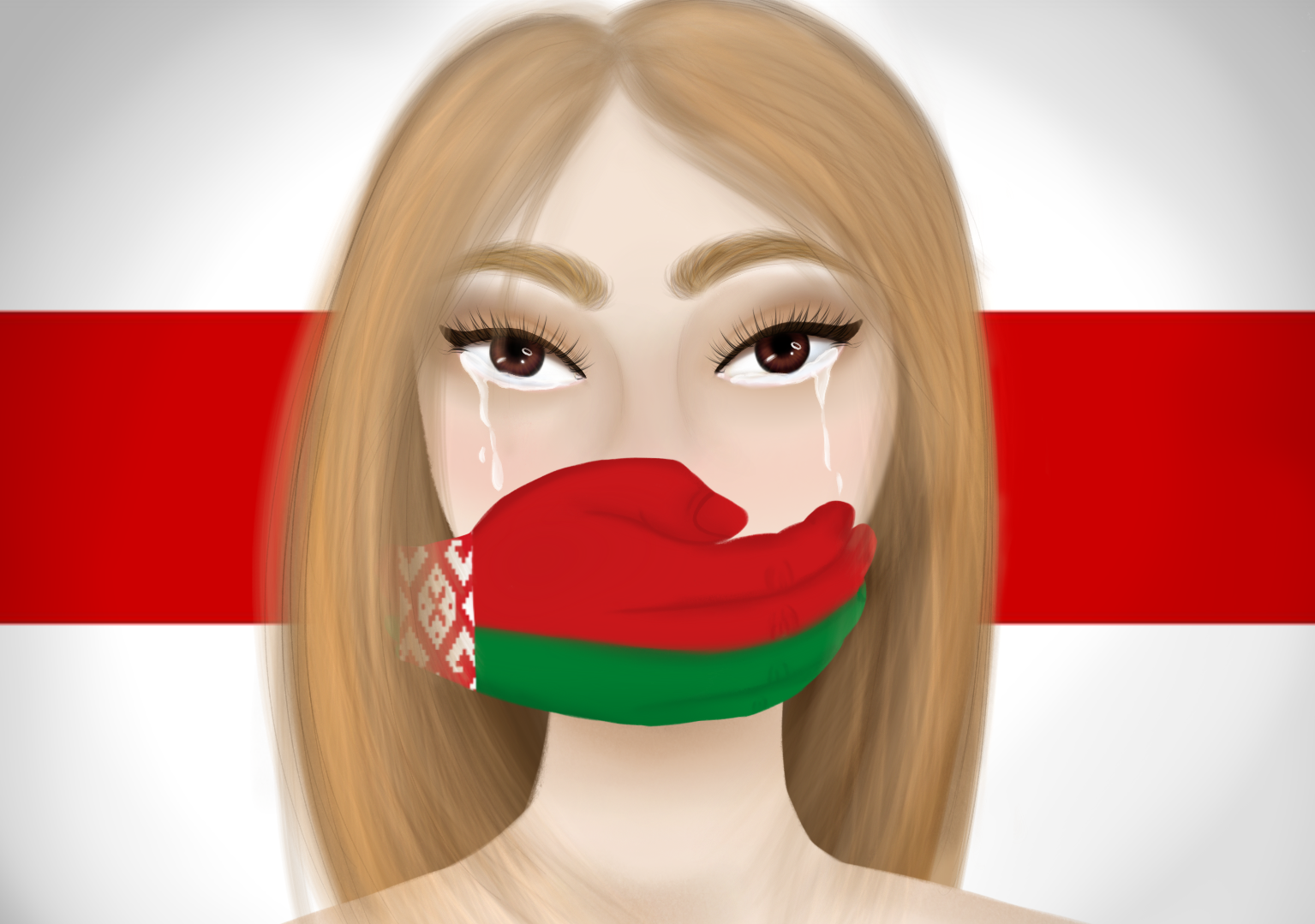

When Art Balenok and Yuliya Aliakseyeva log onto our Zoom call, there is a white-red-white horizontal striped flag behind Balenok’s desk. The flag, which represented Belarus between 1991 and 1995 and the short-lived Belarussian People’s Republic of 1918-19, has become a symbol of popular resistance to the Lukashenko regime. This year, it’s been most frequently seen flying over crowds of protestors staring down armour-clad Militsiya – the national police force of Belarus.

Balenok, a journalist, and Aliakseyeva, who works in Trinity’s Buttery restaurant, are part of a Belarusian diaspora group in Ireland that has come together since July to mobilise support for pro-democracy protestors at home. Aliakseyeva estimates there are no more than a thousand Belarusians in total living in Ireland, and “we’re talking about 50, maybe 70 people who are really involved” in the group.

“Most of us didn’t really know each other before August or July,” Balenok says. “What the events of August 9 triggered was a never before seen unification of all Belarusians, within Belarus and outside Belarus.”

He’s referring to Belarus’ most recent presidential election. Since taking office in 1994, Lukashenko has claimed victory in five elections, none of which have been regarded as legitimate and free by international observers. This year was no exception. The voting was marred by violence, blatant electoral fraud, and the arrest of campaigners and independent observers.

The day after the vote, government officials and Belarusian state media announced that the president had won an almost comical 70-point victory over the main opposition candidate, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, on 84% turnout. Tsikhanouskaya was, up until this year, a teacher and an interpreter with no prior experience of advocacy or political ambitions. She entered the race in May after her husband, blogger and activist Siarhei Tsikhanouski, was imprisoned for “organization or preparation for a grave breach of public order.”

Pro-democracy demonstrations had been held on-and-off since Tsikhanouski’s arrest in May, but with the announcement of the bogus election results, they erupted. “We all came together and became Belarusian, all of a sudden” says Balenok. “Each one of us on that night said to ourselves ‘what can and what am I going to do to help.’”

Belarus experienced waves of popular protest in both 2011 and 2017, but this year’s numbers have dwarfed any seen before. Estimates of the number of protestors in the streets on the biggest days range from 200,000 to more than half a million, out of a population of just 9.4 million. More than 25,000 people have been arrested, at least six killed, and hundreds injured.

“Everyone, everyone has been affected. People from every social class in the country – factory workers, teachers, doctors, pensioners, students, young people,” says Balenok. “Everyone knows someone who has been arrested or who is still in prison.” The universality of the anger at the Lukashenko regime is reflected in the diversity of groups who’ve joined together to oppose him. Women’s groups, conservative Christians, social democrats, greens, and anarchists are just some of the factions who make up the opposition. Even small groups of Minsk municipal police officers have laid down their riot shields, refused to follow “criminal orders”, and recognised Tsikhanouskaya as the country’s leader.

Aliakseyeva and Balenok cite two key factors that differentiate this year’s protests from previous movements. The first is simply build-up; the protests in 2011 and 2017 were “so brutally suppressed, so quickly” according to Aliakseyeva, but people’s grievances continued to mount. “There was not enough critical mass of people” willing to stand in opposition, she says. “But it was all milestones that were leading to today. Everything that was happening at that time was generating momentum that was brought to the election, when it all exploded.”

The second factor is Covid-19. “The way the government handled the pandemic was atrocious,” says Balenok. Lukashenko made international headlines frequently over the past year for his dismissal of the pandemic, calling it “psychosis” and suggesting citizens visit the sauna or drink vodka “to poison the virus”. Balenok describes ordinary Belarusian citizens having to raise money to buy protective equipment for healthcare workers as the government refused to take the virus seriously. “It was people in Belarus who made things happen, and I am sure they saved a lot of lives.”

But the election was “the catalyst”, he says. “We always knew that this was happening. We turned a blind eye. But this year it was just too blatant.” And since then the country has been locked in “civil war, revolution, whatever one may want to call it“. Government forces continue to violently suppress demonstrations, with the United Nations Human Rights Office documenting upwards of 450 instances of torture in August alone. But protestors keep marching, night after night.

“You are constantly on Telegram, checking the news and YouTube, trying to think what you can do to help” says Aliakseyeva, on the experience of watching all this from afar. “We are all badly affected.” Balenok concurs, adding, “It’s as though we were there. Sleep has been affected quite badly. Overall my mental state has not been good at all.”

They’ve been in constant contact with friends, family members and others in Belarus as events have been unfolding. “People have been traumatised for life,” Balenok says. “The price has been so high that whoever takes part believes there is no way back anymore. The situation is never going to be the same as it was before election night.”

Within both the wider protest movement and the Irish group, there is a big emphasis placed on consensus. “We don’t have individual leaders. We don’t want them,” Balenok says. “There has been one of those for the last 26 years in Belarus.”

Nevertheless, they speak admiringly of Ms. Tsikhanouskaya. The opposition activist has rejected the results of the election, estimating that she received 60-70% of the actual vote, and worked from exile in Lithuania and Poland to gather international support. A few days after the election, she founded the Coordination Council, to develop “safe and stable mechanisms ensuring the transfer of power in Belarus.” The European Union and the United States have since ceased to recognise Lukashenko as the legitimate president of the country, and called for new elections.

“The way people feel about her has changed during the last few months,” says Aliakseyeva. “She was starting as a housewife, never taking part in politics. Since then she’s changed dramatically. She’s gathered a lot of very smart, intelligent and good people around her.”

“She’s openly said she’d like to go back home and continue making burgers for her kids,” says Balenok. “Her only presidential program was to become a transitional leader to take the country to a proper free and fair election.” He adds that “her goal was never to become president or to get personal power.”

This emphasis on grassroots organising is reflected in how the Irish diaspora group operates. The initiative wasn’t the brainchild of any individual person but came together organically. “We had a few protests in Dublin and other towns, before there was lockdown,” says Aliakseyeva. “People got to meet each other and make connections. We organised ourselves on a Telegram channel and tried to involve people from a Facebook group for Belarusians in Ireland.”

“All the diasporas are talking to one another now” Balenok adds, “trying to find common ways and effective ways of helping the country and helping the people.” Ireland’s Belarusian community is relatively small, the pair say, compared to those in places like Canada, the UK or Sweden. But they’re trying to build truly global solidarity – “we coordinate our ideas and actions with diasporas around the world.”

The Irish diaspora group has hoped in particular to forge connections between Irish students and their Belarusian counterparts, who’ve played a key role in the pro-democracy demonstrations. They’ve been encouraging people to send them videos with messages of support and solidarity, “to show that those who stand up against oppression and abuse are not standing alone.”

The group’s broader goals are very clear too. They want to “ensure that Ireland is part of a consolidated European front” to help enforce “effective sanctions against individuals and pro-government businesses in Belarus. We want them to play a key role in establishing the rule of law” as Balenok puts it. As part of this effort, they’ve been in contact with political figures in Ireland. “I should mention Senator Malcolm Byrne of Gorey. He spoke in the senate about Belarus, and we couldn’t be more grateful,” says Balenok. They also cite Frances Fitzgerald as an ally and advisor in their lobbying efforts.

More direct approaches are also being taken, according to Aliakseyeva. “Some of our members are helping people who’ve been fired or put in prison. We’re sending money, paying for their food.” Much of their effort has focused on camps in Poland and Ukraine where exiled Belarusians have sought refuge, many lacking basic necessities such as clothes and toiletries.

Though the community in Ireland is small, there are some unique connections between the two countries that Aliakseyeva and Balenok hope will play a part in mobilising support. Ireland hosted many Belarusians during the as part of Chernobyl Children International’s exchange programmes during the 1990s. Indeed, Tsikhanouskaya herself visited Roscrea, Co Tipperary numerous times in her youth. “Nothing is better than a personal touch” says Balenok, somewhat ruefully.

Despite a pragmatic desire for international support in achieving a transition to democracy, they reject utterly the regime’s characterisation of the uprising as a “foreign plot”. “Belarusians never wanted to side with Russia, or the EU, or America, or somehow to be against somebody” says Balenok. “What we want is to be integrated with the world community on equal terms. We don’t want to take sides.”

This pragmatism is a reflection of the seriousness of the situation. Not only are the Belarusian diaspora constantly bombarded with news of the regime’s brutality, it directly affects their own lives. “I’d love to go to Belarus for the New Year and celebrate it with my family,” says Balenok, “but at the moment I am not going to do that. I fear for my safety and my life.” Aliakseyeva nods in agreement.

But despite this steep cost being paid by the Belarusian people every day, at no point is there any question of backing down. Everyone is committed completely to seeing democracy achieved, no matter how long it takes. “It’s impossible to put a timeframe on it, although everyone would love to” Balenok goes on. “And so, we’re looking for that pressure to come from the EU in order to bring this to an end.”

“People are scared and tired,” says Aliakseyeva, “but there’s no way back. No one knows how long it will take, but the regime will go down.”