Student-occupied buildings, outrage at obstinate academic institutions, and an unlivable housing crisis. These are just a few of the details that describe the student movement Take Back Trinity. Just as they capture last year’s protests, they also echo an eerie reminiscence of the 1969 Gentle Revolution – the term used to describe the student protests in UCD which also led to the occupation of an Irish university.

Trinity News spoke to Muireann McGlynn, an fourth student of Sociology and Social Policy, who was involved in Take Back Trinity last year. The movement focused on campaigning against the introduction of supplemental fees in Trinity. McGlynn states that, following a number of meetings of a direct action group, the decision was taken to occupy Trinity’s Dining Hall. She believes that “direct action is the most effective way to bring about change”, “needs to be disruptive” and “make people feel uncomfortable”. However, she adds that a lot of planning and care went into choosing the Dining Hall as a location to occupy as the students wanted to cause “as little disruption as possible to people who weren’t on the College Board” and “not to disrupt people’s education”. People could move in and out of the Dining Hall freely at the start of the occupation, but once College shut the doors, McGlynn notes that the “atmosphere changed”. The following morning, the students decided to end the occupation and the College ultimately backtracked on its plan to introduce supplemental fees.

“Deaglán de Bréadún…recalls the period as ‘a wonderful time to be alive’.”

50 years ago, similar scenes encompassed the landscape of student politics. The “Gentle Revolution” occurred against a backdrop of activism around the world. In May 1968, student protests in France erupted bringing the country to a standstill. Students in the US, and around the world, were protesting against the Vietnam War, and, domestically, the US was experiencing the Civil Rights Movement. Students in Ireland also organised a protest against the War at the American Embassy. Deaglán de Bréadún, who was involved in the Gentle Revolution, recalls the period as “a wonderful time to be alive”.

Similar to now, housing was a major issue in Dublin during this period. Dennis Dennehy, the Secretary of the Dublin Housing Action Committee, was arrested for squatting in January 1969. Students, many from UCD, organised a sit-down protest at the Department of Justice in response. His arrest led to a protest at the Mansion House during the 50th anniversary of Dáil Éireann, and Gardaí clashed with protestors during a sit-down protest on O’Connell Bridge. The Bridge has been the site of recent student activism throughout the years; many will remember sit-down protests more recently during Strike for Repeal in March 2017, and demonstrations by Take Back The City last summer.

In May 1968, Trinity made headlines when Belgian King Baudouin and Queen Fabiola visited the campus. Students held banners accusing Belgium of playing a role in the murder of Congo’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. Gardaí attempted to seize banners from students and altercations followed. De Bréadún sees this as one of the prompts for the Gentle Revolution. Trinity continued to make headlines when on February 25, 1969, Minister for Education, Brian Lenihan Sr., was forced to enter and leave a meeting in the GMB through a window, as the doorway had been blocked by demonstrators protesting the recent closure of the National College of Art.

“Maguire also argues that the SDA applied a ‘socialist philosophy to Irish society’, highlighting the fact that ‘the university educated only 2% of lower-income groups’.”

During the summer of 1968, medical students in UCD held a sit-in protest in the Medical Library in June, demanding that it be kept open during the summer. Students also occupied the Arts Library seeking longer opening hours. By December 1968, tensions were continuing to rise in UCD. The Academic Council had refused to recognise the Republican Club, a left-wing republican group. In response, a group of students, part of Students for Democratic Action (SDA), blockaded a meeting of the Council. De Bréadún recalls how many members of the Council ended up “leaving the room by the window”. De Bréadún also mentions the “Detonator Theory”, the belief that students could “detonate wider unrest as happened in France”, which was being discussed at the time of the protests.

Students in Ireland felt inspired by what their counterparts were doing in other countries. The student protests of 1968 in France lasted for an entire month and resulted in the collapse of the government, followed by a snap election. The students inspired national strikes across the country in their campaign for change, which, at their height, saw up to 11 million workers walk out of their jobs. Bruno Queysanne, an assistant instructor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris during the student protests, argues that, following the protests, “at the level of daily life, and the relationships of people with institutions, there were big changes”. The women’s liberation movement and gay rights movement in France also emerged from the protests. The established hierarchy in society had changed thanks to the student protests. Pay increases and benefits were offered to the workers who had been striking. Many argue that the strikes resulted in the destruction of the father as the ultimate symbol of authority, thus pushing France into the modern world. John Maguire, writing about the Gentle Revolution, echoes this sentiment when he says that “events in other countries gave students in Ireland the idea that they could act collectively to achieve change”. Maguire also argues that the SDA applied a “socialist philosophy to Irish society”, highlighting the fact that “the university educated only 2% of lower-income groups”.

“Over 140 students joined the occupation and stayed overnight, calling the occupied area the ‘liberated zone’.”

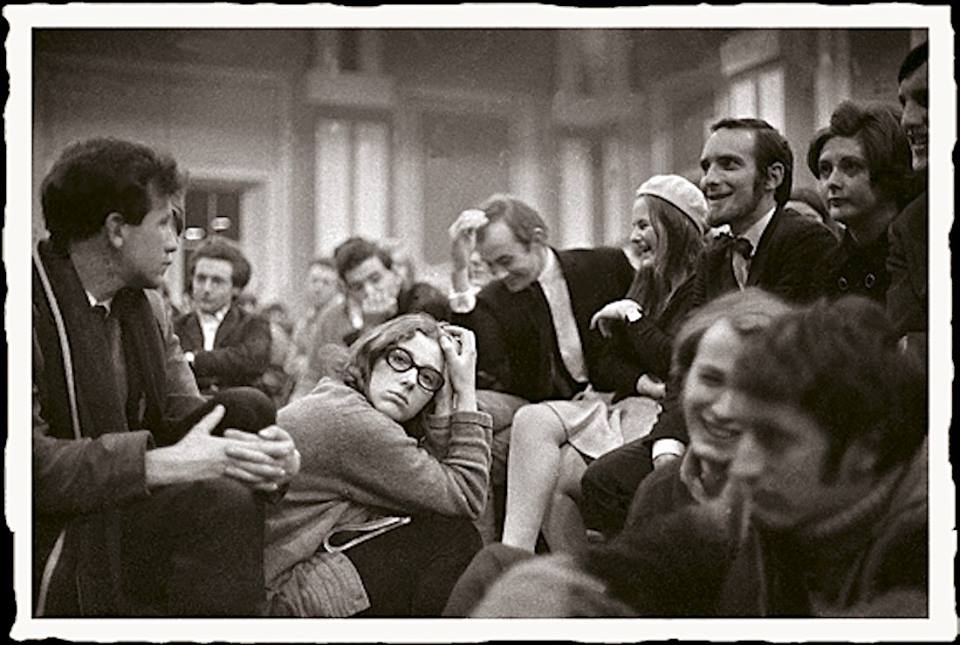

Discontent had been rising about UCD’s move from Earlsfort Terrace to its Belfield campus, which is ultimately what triggered the Gentle Revolution. Students were concerned by the fact the they would be moved to the new campus months before the library was ready. They also voiced their worry about finding accommodation in a part of Dublin which consisted mostly of family homes. On February 25 1969, the Academic Board met with students unsuccessfully. The College administrators had arranged that they would leave the meeting at 10:30pm, but this was not communicated with the students, and therefore it looked as though the staff had walked out of the meeting. The following day, the SDA organised a meeting, during which they outlined key demands about the move to Belfield. They demanded that full library services be available before the move, and that the Governing Body be abolished and be replaced with a 50-50 staff-student board. The meeting ended with the occupation of the administration building. Over 140 students joined the occupation and stayed overnight, calling the occupied area the “liberated zone”. College authorities chose not to get Gardaí involved. Maguire reflects that “the situation during the next 48 hours was such as no Irish university had yet experienced”.

There was a mass-meeting of 3,000 students the next day, February 27, during which a motion was passed that students supported the demands of the occupation, but asked that it be suspended. It was also decided that students ought not to be penalised for their role in the occupation, which duly ended at around 11pm that evening. De Bréadún recalls how “ongoing seminars followed about the nature of society, the role of the university, and the need for social justice”. He mentions how Ivor Browne, an Irish psychiatrist, stated that “we live in a society that is tearing people apart” on a visit to UCD.

UCD ultimately conceded to many of the student’s demands, but stated that they could not hand over power to a staff-student executive as it would be unlawful. Future Taoiseach, Garret Fitzgerald, a senator at the time, said that he would bring a bill to the Seanad to change this. This caused division in the SDA. However, it was ultimately when a mass meeting of the SDA refused to support the workers of Brittain Car Factory, who were striking at the time, that the group became extremely fractured. This is a notable difference from the French situation during which strikes extended to workers across the country. Even today, once a movement has achieved its founding goals, it often disbands when differing political goals make the movement unworkable.

De Bréadún poignantly states that “50 [years] after the Gentle Revolution, there’s still a major housing crisis”. Take Back The City, although not exclusively a student movement, could be seen as the modern day equivalent of the Dublin Housing Action Committee. The movement has been supported by many students, with some involved in direct action associated with Take Back The City. In September 2018, a Trinity student, Conchúir Ó Rádaigh, was arrested following the occupation of an empty property on North Frederick Street. McGlynn, who is writing her sociology dissertation on Take Back The City, argues that the movement has managed to obtain “a huge amount of coverage” and created public awareness of “the fact that there are 200,000 homes empty around the country and 10,000 homeless people. They did a really good job at highlighting how those numbers don’t add up.” She states that despite the fact that “their goals haven’t been fully achieved, local councils are now quicker to act on vacant properties through compulsory purchase orders”. Reflecting on the achievements of the Gentle Revolution, De Bréadún argues that “we changed the mood and the atmosphere, rather than [causing] any fundamental changes in society”, but that “Ireland is a freer society, a lot more liberal, [and] I suppose we can take some of the credit for that”.