Take a seat on the steps of the Exam Hall and observe the swarms milling about Front Square, or recline on the slope of the cricket pitch and examine the flocks gathered around the Pav, the campus watering hole. See the alpha males put down their cans for a brief wrestling match? Notice the cool-looking, long-fringed boy: a crick in his neck from swishing his hair out of his eyes and penguin-shuffling in his super skinny jeans to arrive to class on time?

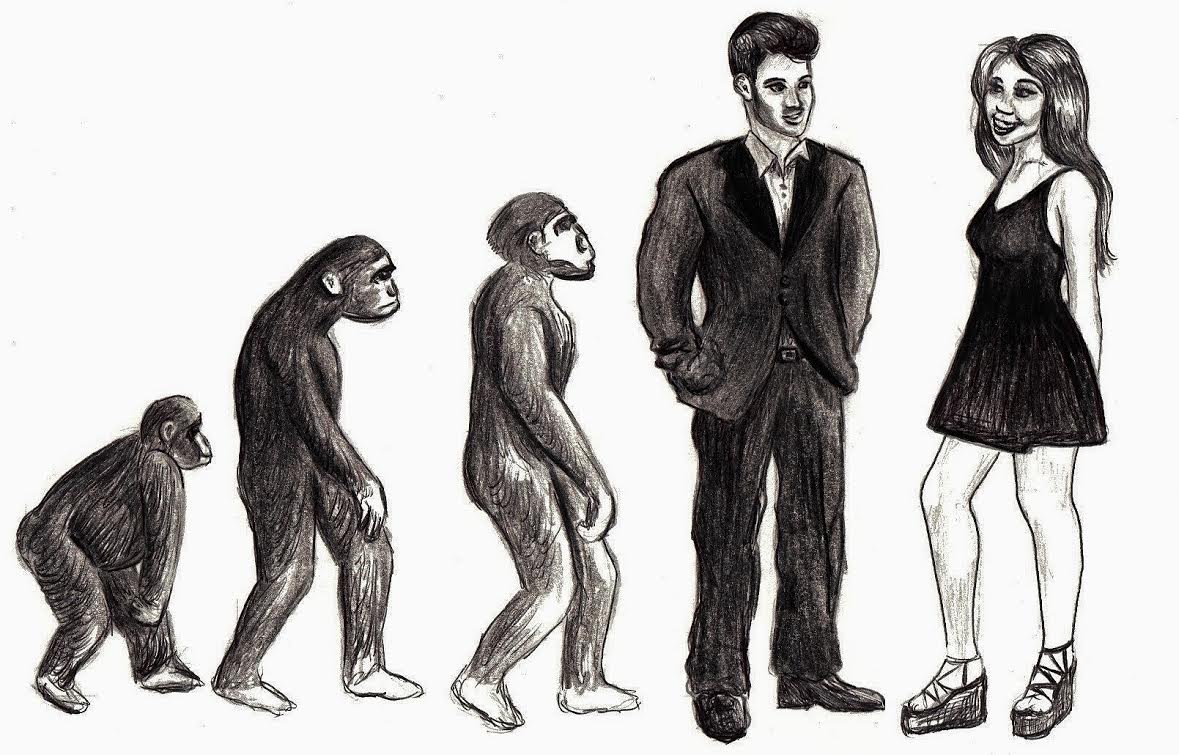

We are animals, after all, and as much as we like to believe we are more psychologically developed than mere beasts, these occurrences are disturbingly familiar to acts of sexual selection known in the animal kingdom, acts which are used by animals to exhibit themselves to the opposite sex.

Sexual selection

Sexual selection is a form of evolution that involves the success of certain individuals of a species (or failures of others) at securing mates. There are two types of sexual selection: intrasexual selection, which involves competition between individuals of the same sex, usually the males, in order to drive away or kill their rivals for free-reign over the females; and intersexual selection, in which males vie for the attention of the females, who then have the pleasure of choosing the more agreeable partner.

Competition is a shared experience of living things. Where resources such as food, water or homes are scarce, animals compete to get the best deal. This is the same when selecting a mate. Imagine you are a young adult stag, sipping at a lake of Pražský outside the Pav, when you see an incredibly sexy doe across the cricket pitch. Unfortunately, your bestie saw her too. You got first dibs and yet he’s willing to break the bro code and fight you for her, and before either of you know it the horns are out. He’s stamping the ground ready to charge, and all you can do is grapple in this primal battle for dominance. Too late, you remember your opponent has been playing rugby for Blackrock for the last six years, and he comes out the alpha male. Male deer, and other such animals, develop their antlers and horns to be used as weapons in combat with other males to earn the right to mate with the females of their group.

Good genes

Some men are clear survivors, while others need to dress to impress. Instead of fighting, the males of other species have found different ways to display their quality. Judging a book by its cover is essential in the wild, because sitting down for a romantic dinner to get to know your potential mate is a really easy way to get yourself eaten. Morphological traits called ornaments have developed by evolution to impress, charm and show off good genes to females. The term “good genes” refers to traits that make an individual the best at surviving, producing offspring that survive well, too.

As a female in the wild, reproduction and child-rearing cost much of your precious time and energy, and you only have a limited number of eggs. You want and deserve the best if you can only afford to raise a few offspring per year, so you must be picky. This is why choosing a male with good genes is so important, as your kids will be born with a genetic superiority and increased chance of living to adulthood. With bad genes they may just end up dying on you, making the whole exhausting experience a complete waste.

Think of the peacock, with his ostentatious plumage and eye-catching colours. His delicately maintained appearance took time and effort, and may barely resemble how he looked the same morning. This sort of display is proof of good genes. It cannot be faked or lied about, since a sick (or hungover) guy, full of bad genes, might not have rolled out of bed early enough to get himself looking so dapper. This concept is known as the good genes hypothesis. Similarly, no one wants to end up lab partners with the greasy guy who smells

like last week’s gym bag, let alone go on a date with him. Unbeknownst to you it’s not only the smell, but a well-groomed male points to his greater disease resistance and efficient metabolism. And if those genes aren’t good enough for you, you need to rethink your standards.

Fashion

Males can be driven to extremes to advertise themselves, so if fashion dictates that tight jeans and good hair are essential features of a girl’s future boyfriend, how far will the boys go to live up to this standard? If long tails are this season’s big thing, the male long-tailed widowbird owns it. They can have an ornamental tail up to one metre in length, but seems to be in fact detrimental to their flight. This is a bizarre circumstance of evolution, which inherently states that the best skills for survival of a species are selected and passed on from generation to generation. So how did this bird develop such seemingly bad genes, while trying to impress the ladies with its good genes?

There are two theories for how showiness could overcome usefulness in a case such as this. The first is Fisher’s runaway process, in which sexual selection drives the females of a species to choose a longer tail, at a point where it was a benefit to the species. Thus the bird with the longest tail gets the most matings, passing down long tails to its sons. The following generations of females are wired to go nuts for longer and longer tails, and so even when the long tail evolves to the point of being obtrusive, it will still be chosen. This process will go on until the detrimental effect of the long tail is so strong that the bird doesn’t make it to the mating stage at all. Like this, you may prefer guys who wear skinny jeans, but if you pick the guy wearing jeans so skinny he can’t get out of them when you make it to the bedroom, you’ll discover the sad fact that he’s an evolutionary cul-de-sac (which is, for sure, the biggest mood-killer in the animal kingdom).

The second theory is Zahavi’s handicap principle. Think of the lad with the thick fringe covering half his face. He’s almost blind, yes, but that doesn’t seem to be stopping him. In fact, his ability to function adequately despite the handicap of his blindness just about proves how incredibly good he is at surviving. This happens in the wild with male signals such as bright colouring, mating dances and birdsong, all of which attract predators, and show the ability to survive regardless of this major threat. Whether it’s a runaway effect or a handicap, as long as the cost is outweighed by the advantages to breeding potential, both principles will drive males to be extreme show-offs.

We can find examples of animal behaviour amongst ourselves in unexpected places, but in some cases it appears as though humans have outsmarted evolution. Sometimes the beta male sprawled on the ground with a broken nose gets the sympathy from the girl, while the alpha male looks like a jerk. And since we have developed contraception, we thankfully don’t need to consider every suitor as a parent to our potential children.

Illustration: Sarah Larragy