Dylan Lynch examines the recent findings in relation to E-Coli bacteria.

Let’s face it: we have all had our run in with the cheap all-you-can-eat buffet and paid the price for it afterwards. The infamous Escherichia coli or E coli bacteria is one of the leading food-poisoning bacteria, the little rod-shaped bacterium having caused 16% of outbreak-related hospitalisations in the US throughout 2009 and 2010. Even more worrying is the fact that for three of the four years leading up to 2009, Ireland had the highest incidence of E coli poisoning in the EU – a whopping seven times more than the EU average. However a recent discovery has been made which may clear its name.

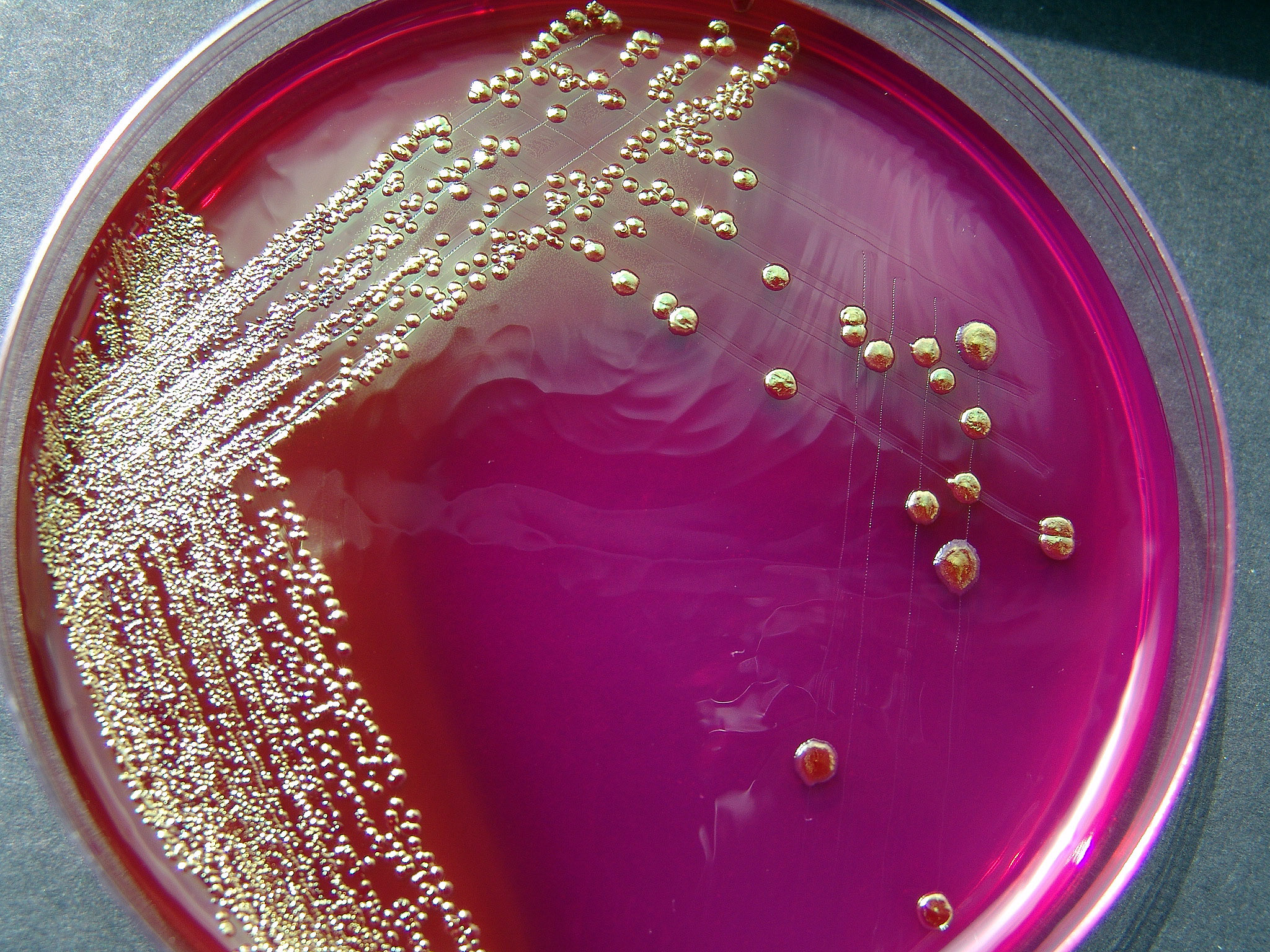

A South Korean research team at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology has managed to produce petrol from the E coli bacteria. The team, led by Prof Lee Sang-yup, published their findings in late September. The genetically modified E coli bacteria were fed glucose, a base sugar unit often found in energy drinks, and the enzymes that they then produced converted free fatty acids (or FFAs) into what Lee describes as “chemically and structurally identical (compounds) found in commercial fuel”.

There are huge advantages to this new biopetrol/biogasoline. For example, the biopetrol has a 30% higher energy content than our traditional biofuels. The process requires modified E coli and glucose, which is found in plants and other non-food crops. The real significance of this discovery is that it does not require the catalytic cracking of crude oil: a process in which crude oil is pumped into a large column and broken up into its individual and more valuable parts, knows as “fractions”. This discovery allows us to convert glucose and waste biomass straight to petrol.

So is this the answer to the energy crisis, or a double-edged sword?

While the efficiency of this conversion is quite low at present, it brings to mind the question: are bacteria-powered cars as far away as we think? Scientists have previously been able to procure biodiesel from bacteria, but with this new breakthrough in biopetrol production, it seems we could have “renewable” fossil fuels in the near future. This could lower the price of fuel, and create huge employment in the petrochemicals industry.

“Even more worrying is the fact that for three of the four years leading up to 2009, Ireland had the highest incidence of E coli poisoning in the EU – a whopping seven times more than the EU average.”

However, not all response to the discovery has been positive. Science bloggers have expressed concern that the discovery may lead to more long-term pollution, and an increased reliance on fossil fuels, when we should be moving in the direction of cleaner renewable fuels such as solar, wind and tidal power. The most prominent issue on people’s minds seems to be the risk to the environment from increased petrol and hydrocarbon (compounds which contain hydrogen and carbon, such as all fossil fuels) supplies. Each of the last three decades has been warmer at the Earth’s surface than any preceding decade since 1850, and the rate of sea level rise since the mid-19th century has been larger than the mean rate during the previous two millennia. Over the last two decades, the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets have been losing mass, and will continue to shrink almost worldwide, especially if we maintain the greenhouse effect at its current levels.

Another main argument against this new E coli-based biopetrol is that it requires a huge amount of biomass. There are fears that this process will cause a spike in the price of food, as crops begin to be used for energy generation rather than feeding people. However, Lee rejects that argument, stating in an interview that “there is tons [sic] of biomass that is being wasted on Earth. There is a lot of biomass which we can smartly use”.

So, how soon until we have E coli fuelled vehicles?

While this technique is an outstanding discovery and could shape the future of our existence and energy crisis, we may have to wait a very long time to see it being used to fuel cars and trains. At the moment, the process is in its infancy stage: According to the research publication, it has only produced 580mg of gasoline for every one litre of glucose fed to the bacteria. But we could soon see E coli sourced vegetable oil in our supermarkets and E coli-based make-up in our pharmacies. With our ever-advancing industries and scientific knowledge, a new age of pathogen-based biofuels may just be around the corner.