Early days

The mission’s first setback came before the craft had even left the surface of Earth when the Ariane-5 rocket that was supposed to take the spacecraft to space exploded shortly after launch of another separate mission in December 2002. At the time, this marked the fourth failure of this rocket type since 1996. With billions of European taxpayer’s money funding the project, the team working on the Rosetta mission decided to postpone the launch of the spacecraft until the failure of the Ariane 5 rocket could be understood and resolved. The new launch date was pushed back from January 2003 to March 2004. As a result of this decision, the plan to originally study the comet 46P/Wirtanen had to be abandoned and instead, the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko was chosen as the principle target of the Rosetta spacecraft.

As a result of this change in destination, the mission trajectory, or the path followed by the spacecraft to reach the comet, had to be changed as well. This provided the team behind Rosetta with a new challenge because this new path included an additional fly-by of Mars, something not included in the original planning of the mission and spacecraft design. A fly-by, also known as the gravity assist, is a manoeuvre where the orbit and the gravity of a planet or another astronomical body to change the path and speed of a spacecraft. For the Rosetta spacecraft, this included spending 24 minutes in the shadow of Mars. Since Rosetta is the first spacecraft to rely solely on solar energy to as a power source, this provided a big problem. The spacecraft had to be re-programmed leading up to the Mars fly-by to prevent it from reacting to the lack of sunlight which could have had disastrous consequences for the mission. Following the tense minutes spent waiting for Rosetta to pass through the shadow, a signal was eventually received craft, meaning a huge relief for the team and a continuation of the mission.

Arrival

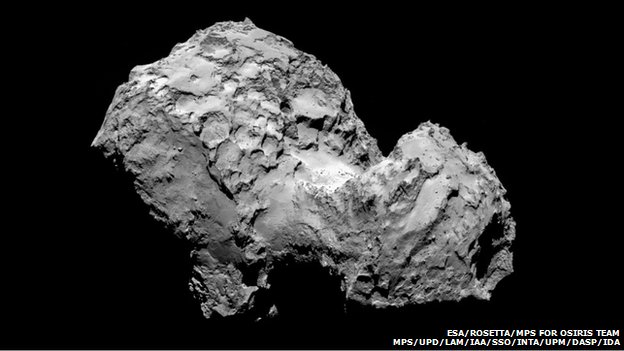

When the spacecraft did eventually reach the comet, a new problem presented it when it was seen that instead of the expected oval shape, the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in fact had a more irregular shape which made it difficult to find a suitable landing site for the lander Philae. Following analysis of the comet’s surface while Rosetta remained 100km above, a landing site called Agilkia was later recognised as the most suitable place to land Philae and the space probe was shortly afterwards deployed by the Rosetta spacecraft on 12th November 2014.

If any member of the team involved with the Rosetta mission was hoping for a smooth and problem free landing, to make up for earlier problems, then they were to be extremely disappointed. Upon landing, Philae’s landing gear failed to attach properly to the surface of the comet twice, with the lander remaining suspended in the atmosphere at a height of 1km for an hour and fifty minutes after the first attempt. Although it landed at the planned location the first time, the second time it came down at an unknown location in the shadow of the comet, leaving it unable to recharge its batteries and at risk of running out of power. At the time of writing this article, the exact location of Philae is still not known and the search is continuing using high-resolution images of the comet’s surface obtained by the Rosetta spacecraft which is still in orbit around the comet. It was estimated that the lander had about 60 hours worth of battery when it landed on the comet. An attempt was made to move Philae into a position where it could better receive solar energy but the process resulted in draining the battery further. The lander has now completed its primary mission of sending back the data that has been collected so far by its instruments. At the present moment, Philae has gone into hibernation and there is no communication being received from it. However, the scientists are remaining hopeful that as the comet comes closer to the sun that enough sunlight will hit the solar panels in order to generate power and bring Philae back to life.

Looking back, there have been many obstacles to overcome to get this far with the mission, with the last week being described as a ‘rollercoaster’ by Fred Jansen, ESA’s Rosetta Mission manager. However, although the Rosetta mission has been blighted by problems, it still does not take anything away from the fact that they were the first to land a probe on top of a comet. If anything, it is a testament to the dedication and determination of the people involved.