O’ Callaghan was born in 1954 in Chicago. Her great-grandparents emigrated from Ballyjamesduff in County Cavan. When she was in high school she wrote a poem in the shape of a tree, which earned her high praise from her English teacher. After this she continued to write poems. She says the poems she wrote during this period were “about nothing, just shooting the breeze.” It was not until she came to Ireland that poetry became such an important part of her life. She arrived in July 1974, two days after her twentieth birthday.

Two poetry readings that she attended in Dublin that autumn were to change her life forever: “In September I saw a little ad on the back of the Irish Times for an open mic night. It was an invitation for anybody who had some poems to come and read them. It was over in this place called the Lantern Theatre, which was in a basement in Merrion Square. So I went there, and I brought my little scraps of paper with my handwritten poems on them, and I read my poems, and I went home. Three weeks later, I saw another ad on the back of the Irish Times, and it was for a reading by Seamus Heaney in the Lantern Theatre. At that time I didn’t really know where I was. I was literally on Mars. But I knew where the Lantern Theatre was. So I went along to this reading, and when I went down the stairs to the basement they said it was all full, and that they couldn’t let me in. To tell you the truth I had never heard of Seamus Heaney. I didn’t know who he was. He was very famous already, but I had never heard of him. Anyway they came back a few minutes later and said that they had managed to fit a few more chairs in by putting them on the stage beside Seamus Heaney. So I sat on one of those. And then he read, and then there was an interval. During the interval I heard somebody calling my name out. I was confused because I didn’t know anybody there. And the person who was calling my name was Denis O’ Driscoll, who I would eventually marry.”

Dennis O’ Driscoll, who died in 2012, was considered a giant of Irish and European poetry. He was one of the most respected poets and critics of his generation. Although he had a full-time job in the Revenue Commissioners, he produced numerous volumes of poetry, essays and criticism. At the Seamus Heaney reading where he and O’ Callaghan met, he approached her during the interval because he remembered her from the open mic night: “Dennis said: ‘I heard you reading your poems here a few weeks ago and I thought they were really good. I was wondering if you ever published them?’ And I said: ‘Are you kidding me? No, never.’ Dennis really liked my poems. I’ll tell you what he said, which I thought was a complete chat up line. All my poems were handwritten and he asked if I ever typed them up. I said I didn’t, and he said: ‘Oh, I have a typewriter in my house.’ And it turned out that he only lived two minutes down the road from me. I was on Leeson Street and he was on Appian Way. So I went over and typed up my poems. And he picked two of them and said: ‘You should send these to New Irish Writing in the Irish Press.’ I wasn’t sure because the poems were so American, but I sent them anyway. And they were published.”

This was the beginning of a new period in Julie O’ Callaghan’s life. She never went back to live in the United States: “I went back and told my parents that I was moving to Ireland. And I never finished my degree, which was a bit of a thing.”

She took a job in the library in Trinity, and continued to write poetry. After being published in the Irish Press, she was published in the Times Literary Supplement. In the eighties she had her first book of poetry published, by Dolmen Press. They read her work on O’ Driscoll’s recommendation: “Dolmen Press published Dennis’ first book. It was called Kist. That’s a Scottish word. It means coffin, actually. He put in a word for me with Dolmen. They had a look at my stuff, and they took it. I didn’t even struggle. It was way easier in those times. This was 1983. It wasn’t such a rat race. Poetry just got real big here. It’s a hard thing to get going in. The thing is that Irish poetry has become so famous internationally. That made it harder.”

You never call yourself a poet. If somebody asked me what I do I would say I work in a library. Anybody who calls themselves a poet is not a poet. Only other people can call you that.

Since then O’ Callaghan has published numerous volumes of poetry, including some for children and young adults. She received the Michael Hartnett Poetry Award in 2001, and is now a member of the Aosdána. Her poetry is popular largely because of its humour, which often casts an off-beat light on the most banal of situations. Almost all of her poems are written in an American speaking voice. She is obsessed with tones and rhythms of the Chicago vernacular, which she finds hilarious.

However, she claims she only began to find it funny after moving away from her home city: “When you go away to a different country, you understand how hilariously funny your own people are when they talk. I could only hear myself after coming to Ireland. After being away from America, I could hear how utterly hilarious a lot of the speech is there. But if I hadn’t left I wouldn’t have heard that. Americans have this wacky way of looking at things which I did not notice until I came here. It’s just so funny. Every time I go back I’m just listening. Because they say the funniest things. If I walk past the queue for the Book of Kells, I can hear the people from Chicago. They talk through their nose. When I was in high school in Chicago, a woman was hired to come and teach us elocution.”

When she says “the way people talk”, it seems that O’ Callaghan is not only referring to the sounds, the slang and the rhythms, but also to the shared outlook on life that can be contained within the shared speech of a group of people. The characters in her earlier, more light-hearted poems always seem very small, and even confused by life. They insert meaning into their lives by small defiances in language. And it is always in the informal speaking voice that these defiances manifest themselves: “Me an my buddies / have an ok time down at da garage. / We ain’t soft in da middle like come people / I don’t care ta mention.” The heart-breaking poems about her father’s death that were published in 2000 still use a speaking voice, but it is her own. It is one of pure grief, but it remains honest and unworked. O’ Callaghan is up front about her lack of technical poetic knowledge: “I have no notions whatsoever. I don’t know anything about poetry. Rhymes, metres and all that. It’s just not happening up there.” The patterns of human speech are what give structure to her verse. However, one suspects that she might know a bit more than she lets on.

Her modesty is such that she will not even call herself a poet: “You never call yourself a poet. If somebody asked me what I do I would say I work in a library. Anybody who calls themselves a poet is not a poet. Only other people can call you that. It’s such a high up thing that you can never say that about yourself without sounding kind of smarmy. I would never presume to call myself such a thing, especially in Ireland. Even Seamus Heaney never called himself a poet. He was filling in a form once to register his kids for school in Wicklow. He had to write down his occupation and the school told him to write ‘file’, the Irish word for poet, but he didn’t really want to.”

It is hard to separate Julie O’ Callaghan’s personal life from her literary life. The omnipresence of her late husband Dennis O’ Driscoll blurs everything into one. When she entered into a relationship with him, poetry was part of the deal: “He was a genius. He was an absolute poetry nerd. He loved poetry. His whole life was poetry. Everything to do with him was poetry. It was a miracle that I met him. And if I hadn’t met him I wouldn’t have kept writing. It’s such an un-fun thing to be doing.” She did write before she met him, but it is as if his mere presence inspired her to keep going with it, at least in the early days: “Dennis used to put my poetry into three piles: adults, children and garbage. The garbage pile was always the biggest. Since I was twenty years old, he’s been telling me what the flipping hell to do with my poems. He used to call himself my coach. He said poetry was like sports, and the coach has to cheer you on and get you going.”

It is clear from speaking to her that she is still struggling to come to terms with O’ Driscoll’s death. She is on her second career break from the library in Trinity, and is currently living in Naas with her horse and dog. She has been writing poetry about Dennis. It seems to be her way of coming to terms with death. She did the same thing when her father died. She says that this coping strategy sometimes worries people, but that it works for her:

“The newest poems are going to be a bummer. I mean that’s all they can actually be. Because everything’s gone to hell. I spent all last year writing poems about Dennis and his death. I have like a hundred poems. It’s very hard. And then I think maybe I should stop thinking about it. But I’m just working through it really. Some people say I should go to a counsellor and get help. But for me, it’s much better to write a poem. Because you’re trying to work through what the hell is happening in this world. After he died I was asking myself: ‘What now? All my family is in America. What do I do now?’ And then I thought: ‘What would Dennis do?’ And I know he would just say: ‘Poems, poems, poems.’ It’s the only thing I know how to do. You’ve got to deal with what you have. This is the only way that I can figure it out. You can go for a couple of days if you don’t stop, you don’t think about it. I guess a lot of people do that. Clean the garden, scrub the house, get a new kitchen, go on a vacation, run around like a lunatic. I suppose that works in a certain sense. But I can’t do that. I have to stop and think about it. And it’s really hard. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy, this situation that I’m in.”

If the poems on the death of her father are anything to go by, the forthcoming ones about O’ Driscoll will be intensely personal and difficult to read. They will also be marked by the fact that he himself is not there to edit them. The long poem Sketches for an Elegy, the most personal account of O’Callaghan’s father’s death, was assembled by O’ Driscoll from a series of hastily written anecdotes, thoughts and images: “Dennis put Sketches for an Elegy together. When my father died I was freaked out. You can tell from reading that poem. I just got a notebook and just started scribbling little pieces. My brain was having a nervous breakdown. Dennis took the pieces and assembled them. That’s why the new ones about Dennis are so hard. Because there isn’t another person on earth who can do the job of Dennis O’ Driscoll. I’m trying to second guess what he would think, which is not good. But it’s all I’ve got.”

Although she feels like the current poems are part of her personal grieving process, she is sure that they will be published. Her publisher, Bloodaxe Books, will want them, and as a member of the Aosdána she has an obligation to produce. That said, she makes it very clear that she is “not in a rush”. She is not sure whether there will be one long poem, or a book of shorter ones. Similarly she is not sure where her life in general is going to go from here. For the moment, she is content to stay in Naas and try to write her way through to some kind of understanding, or acceptance: “I don’t know what’s happening. That’s the truth. People are asking what I’m going to do, where I’m going to go. And I have no idea. Everybody is so freaked out that Dennis is gone. Everybody’s waiting for me to say something.”

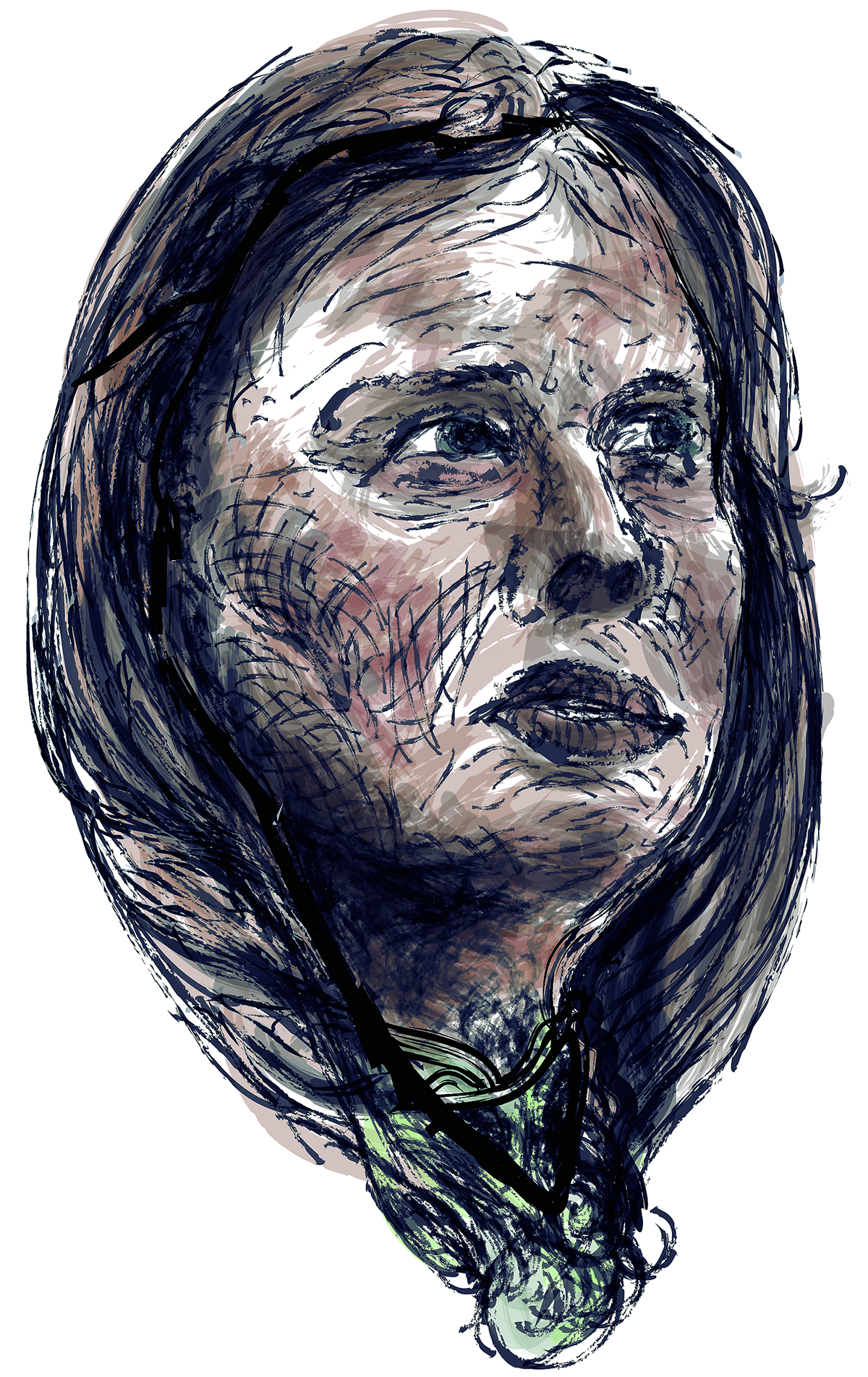

Illustration: Naoise Dolan