Some days, I just want to scream it out from the rooftops so that I can stop having these individual conversations; others, I wonder why I bother telling anyone at all – it’s nobody’s business but mine, after all. Today is one of the former days. This is my rooftop. Here is your half-hour long vocabulary lesson, and a little about my experience, and why you should even care. Here’s my once and have done with it. Hi everyone. My name is Hannah. I’m a first year CSL student. I grew up in Virginia, in the US. I knit while watching movies. I’m a cat person. I make really excellent banana bread. Oh, and I’m asexual.

The vocabulary lesson

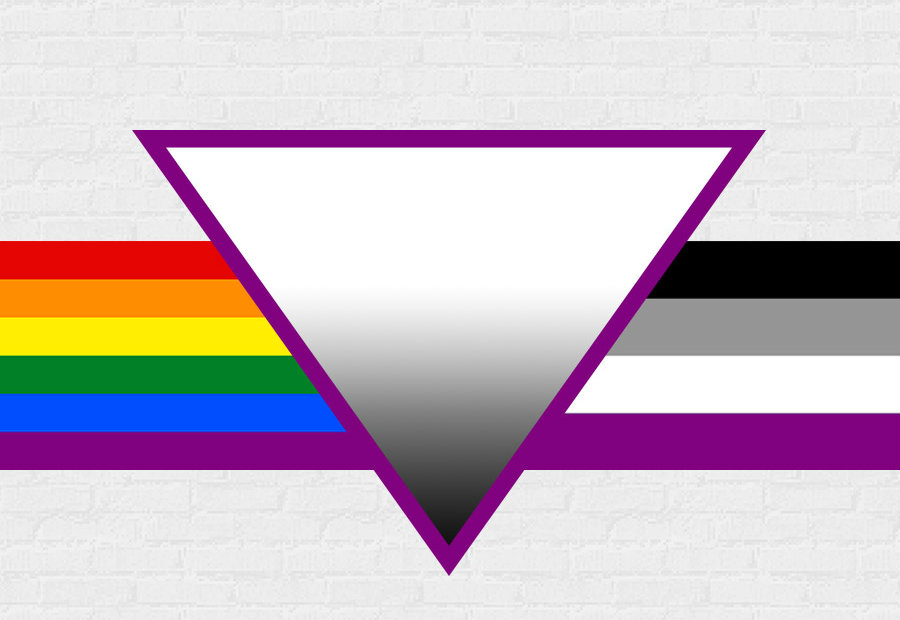

Asexuality is defined as a lack of sexual attraction. Of course, people are more complicated than that, so everyone who identifies as asexual has their own idea of what asexuality means for them. Some asexuals are sex-repulsed, some are indifferent, some enjoy sex. Some asexuals are also aromantic, others desire a romantic partner in their lives.

Sexuality, like more or less everything else, is a spectrum. On one end, we have asexuals (aces); on the other, allosexuals (those who experience sexual attraction). But there’s still a bunch of space in the middle! People along the middle areas of this spectrum may identify as demisexual (demi) or gray-asexual (gray-a). And some people choose to eschew labels all together. Asexuality is not linked to trauma or mental illness. Please don’t confuse asexuality with celibacy, which is where someone feels sexual attraction but doesn’t act on it. Sexuality is an orientation, not a choice.

Why was the idea of sex in the abstract fine, but enough to induce nausea and panic when I tried to add myself into the equation?

Okay, so now that you know what asexuality is, we’re going to go ahead and skip a large number of questions that are generally considered to be in bad taste. Or rather, we’ll skip the answers, because it’s important you know not to ask these questions to people. Seriously, guys, why would you ask anyone these?

Some questions you should never ask an asexual

- “So… you’re like an amoeba?”

- “Have you ever had sex?”

- “So, you really want to have sex, but you just, like, don’t?”

- “If you’ve never had sex, how do you know you’re asexual?”

- “Do you masturbate?”

- “Are you sure you’re not just gay?”

- “Have you had your hormones checked?”

- “Were you, like, abused?”

- “Don’t you think you’ll feel differently in a few years?”

- “Why do you feel the need to be a ‘special snowflake’?”

My experience

I started self-identifying as ace around the beginning of high school, which is about age 14. This is a huge oversimplification, so let me expand on how, exactly, I came to identify this way. I think it’s really hard to describe this process I went through, why it was so important, to allosexuals, particularly to straight people, but I’m going to try.

Puberty is pretty much universally awful. Your body goes through changes without asking you, and suddenly you have all these new urges and feelings. At least, you’re supposed to. I never did. That’s how it’s taught, year after year, in health class, or sex ed, or “family life education” (actually what my state refers to it as, no joke). “Someday soon, you’re going to be looking at someone, and you’ll want to do things with them. You will.” Generally, they encourage you not to do these things, but the underlying assumption is that, deep down, you must want to.

But it’s not just taught in schools. Think about all the media you consume. How many movies have you watched in the last year that didn’t have a romantic subplot? Sex sells. Relationship drama is considered necessary to a complete narrative. And representation matters – all these things that are shown to you, time and time again, are coded as “normal”. Not wanting them means that something must be wrong with you.

Why was the idea of sex in the abstract fine, but enough to induce nausea and panic when I tried to add myself into the equation?

Over and over, that is what I was told – by my teachers talking about what made a healthy relationship, by the media playing image after movie after love song, by friends giggling together over crushes, by my parents gently teasing me about any boys (and, later, some of the girls) I hung out with. These things are all meant well, of course. But over time, pressure begins to build up. “Late bloomer” begins to look more and more unlikely. Words like “frigid” and “prude” start to get tossed around. I spent some time seriously considering whether I might be gay – but kissing girls sounded just as gross as kissing dudes.

Why didn’t I want these things that everyone else wanted? Why was the idea of sex in the abstract fine, but enough to induce nausea and panic when I tried to add myself into the equation? Fortunately for me, the internet was a thing when I was in high school, and I managed to stumble across asexuality.org. I don’t remember what I was looking for originally, but I do remember what it was like to click on the FAQ page and realise, this is me.

Finding this word is one of the best things ever to happen to me. Having the vocabulary to describe the things I felt was liberating. Suddenly, I was valid. I was a part of a community. There were other people who felt the way I did, and they were – for the most part – happy. There was a perfectly reasonable explanation for my existence. I wasn’t broken.

Why you should care

If the rest of this article hasn’t made it clear yet, most people have no idea what asexuality is – which is kind of surprising, because most estimates put asexuals as being about 1% of the population. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but it means there are probably about 46,000 of us in Ireland, with possibly over a 150 attending Trinity. The odds are good you know someone on the asexual spectrum.

I’m generally really happy with my life. But that doesn’t mean that everything is easy.

This lack of visibility is really harmful. A lot of aces go much longer than I did without discovering the community (which is mostly online), or never find it at all. They feel the same way I did: broken and wrong. And even once you know the words, it can be really hard to say them when you’re not sure if people will understand. You have to worry if they’ll believe you; you have to worry if they’ll smirk and say something inappropriate. In some cases, you have to worry about whether or not they’ll still want to date you when anything beyond cuddling and kissing is off the table, and honestly you’re not too enthusiastic about the kissing, either. You’ll have to worry about other people assigning a lower value to your relationship, because in their minds, sex and romance are permanently fused.

Nothing hurts worse than trusting someone with a piece of yourself, and having them laugh in disbelief. I’m generally really happy with my life. But that doesn’t mean that everything is easy. I’ve been really conflicted about publishing this with my name on it, because I’ll be honest with you: I’m scared. I’ve faced enough rejection to be perfectly willing to crawl into a hole and never come out. Every time I hear someone say something that, essentially, doubts my existence and validity, I want to cry.

But I think that these things have more meaning with a name and a face. Asexuals don’t just exist in the abstract, we’re here. We’re real people, just like you. And there’s nothing wrong with us.

Illustration: asexuality.org