When one thinks of eating disorders, one automatically thinks of anorexia nervosa, the most spoken-about eating disorder. With anorexia, the scars of the disorder are borne physically. It is clear that the person is underweight. However, there also exist other types of eating disorders, particularly among athletes that are harder to define, more difficult to notice, and almost impossible to catch.

Orthorexia nervosa, a relatively newly identified eating disorder, shares characteristics with anorexia nervosa. Yet rather than restricted eating, it involves obsessive healthy eating. The term orthorexia was coined by Dr Steven Bratman in 1997 in the USA as a “fixation on righteous eating” but has yet to be officially recognised as a clinically diagnosed eating disorder.

When healthy eating becomes unhealthy

Righteous, pure eating is very much a phenomenon of the 21st Century, a quick scroll through Instagram reveals pages dedicated to clean eating, paleo diets, gluten-free, dairy-free, sugar-free, and everything-free recipes. Health food is everywhere, which is a good thing. We are making an active effort to live healthier lives and combat obesity. The term orthorexia serves to define the grey area between what is considered to be a healthy diet and a clinically diagnosed eating disorder.

The difference between orthorexia and anorexia is that while anorexia is a fixation on being thin, orthorexia is a fixation on following a strictly healthy diet, and banishing all impure substances from the body. It is not, as some might believe, an obsession with exercise. Although in most cases enthusiasm and often dependence on exercise play a huge part in establishing a “clean and healthy” body for the orthorexic person, it is not, however, a key characteristic.

Prevalence in athletes

Orthorexia is far more nuanced than other eating disorders because it starts out with the intention of improving general health. In particular, the prevalence of eating disorders in athletes is a huge question yet to be properly investigated. The first study to examine the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in athletes was undertaken in 2012 and showed high incidences of orthorexia nervosa across both male (30%) and female (28%) athletes in a range of sports including running, swimming and basketball.

It is normal for elite athletes to maximise their nutritional intake for optimal benefits and attempt to follow as healthy a lifestyle as possible for the benefit of their sport; a distance runner will try to achieve a low body fat percentage to be lighter and more agile, a thrower will emphasise strong core and upper body strength resulting in a larger body size, and a dancer will need stronger than average legs. This is achieved by exerting strict dietary control to reach a certain weight or body shape in conjunction with a specific training plan. Not just limited to elites, anybody committing to a sport will endeavour to give themselves the best chance possible at a good performance. Yet, the uncertainty lies between when these healthy eating habits become unhealthy eating behaviours.

It is possible that orthorexia begins similarly in athletes and non-athletes with a desire to eat cleaner foods. But athletes are less likely to be questioned because they are eating “clean” for the benefit of their performance and health, rather than a non-athlete who eats clean for the benefit of their health alone. The additional motivation of performance present in athletes is another possible barrier to the detection of this disorder.

Athletes are therefore prime candidates for orthorexia, particularly in judged sports such as diving, gymnastics, and ballet, although it would be incorrect to conclude that all athletes are orthorexic. It is a condition found more frequently among athletes and therefore athletes are at a higher risk of developing the disorder. In an area where both elite and amateur athletes are vulnerable it should be better surveyed and studied because as we know, mental health is fragile, and it could be a bigger problem than we realise.

Detection and intervention

It is very easy to get sucked into an obsession about food. For elite and non-elite athletes, this can involve striving to achieve a perfect performance body, starting out as a conscious decision to reduce bad foods and increase good ones. Your coach, if they engage in this type of dialogue with you, should be happy to hear you are taking care of your diet, as it will have an influence on your performance. However, it is next to impossible to survey the eating habits of someone who may be suffering from orthorexia because on the face of it, they are following the perfect and ideal diet for an athlete. A lot of qualities of a good athlete are similar to symptoms of orthorexia, such as a strict, healthy diet and excessive amounts of exercise. Why then, would a coach encourage their athlete to eat bad foods when it is not really in their interest? It is likely that they will encourage and support the maintenance of a balanced diet. The issue lies in the fact that a coach cannot see into the mind of an athlete, and cannot tell whether the behaviour is normal, healthy or obsessive, leading to little or no intervention.

Orthorexia often occurs during periods of transition, such as the move from school to university sports or a change of coach who may encourage a new type of training. This transition period also includes short time periods of following a specific diet to prepare for a competition. The person should be able to transition smoothly, or in the case of a short-term diet, to return to normal eating habits after a specified date. Orthorexia occurs where equilibrium is not achieved or re-established, when the person is unable to transition back into a normal lifestyle. The obsession becomes long term, leading to high stress, difficulty in social situations and the decline of your mental health.

I have heard stories of athletes going on no-carbohydrate diets for a period of time, or living entirely off soup a week before a race to get to race weight. It is unclear whether this amounts to orthorexia or not. It certainly seems extreme to cut a whole food group out of your diet, particularly when carbs are an excellent and primary source of energy. On the other hand, the soup diet was temporary with a particular goal in mind: to shed excess pounds for a particular race. This does not fit in with the criteria of orthorexia as it is not a long-term obsession, while cutting carbohydrates out of your diet seems to resonate with the idea of an eating disorder.

This leaves us with a serious question: how do we detect orthorexia in athletes, and how do we distinguish between good-healthy eating, and obsessive-healthy eating? One thing is clear, this area is majorly under researched as it is a relatively new phenomenon. It needs to be given more attention, particularly in relation to female athletes who are already more susceptible to acquiring an eating disorder by virtue of being a female in a society that often values a woman’s physical appearance as much as or even more than their intelligence or athletic ability.

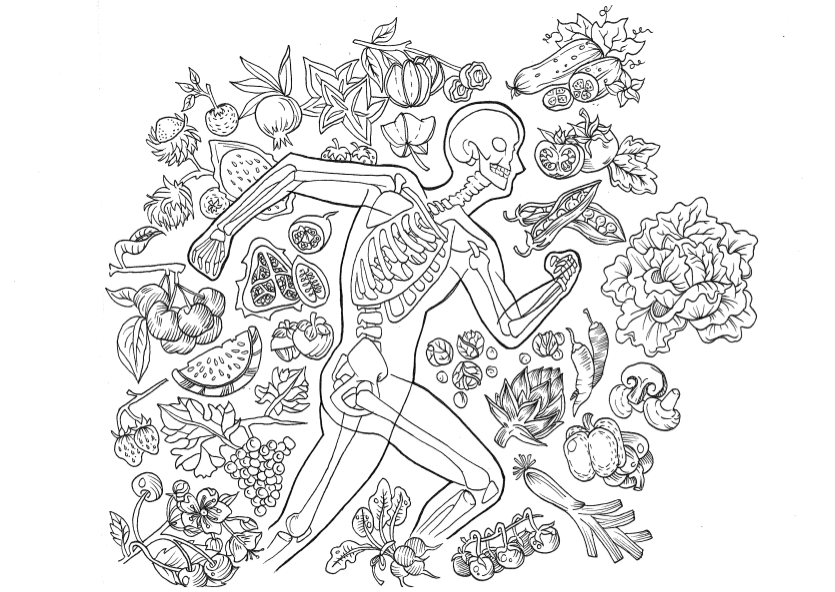

Illustration by Nadia Bertaud.