With sabbatical elections only a month away, candidates are putting the final touches to their manifestos, preparing husting speeches, and drafting potential flyers – all in preparation for the run up to polling week, the results of which will determine a large aspect of their lives for the following year.

The stakes are high with free accommodation and a paid job on offer for the most preferred candidate in each race. Yet, according to a former polling-station staff member who will remain anonymous, the high stakes do not mean the system is infallible – indeed, far from it. Our source claims there are several possible ways someone could unfairly influence the results of any election in Trinity, including referendums, class rep elections and sabbatical elections.

Methods

The first way involves former students. Our source claims as long as you received a card during your time at Trinity you will be able to vote next month: “if your student card has expired there’s no way of telling.” While it’s not impossible that a polling staff member might catch this if they check the date, our source claims that “they never check student card date – they at most check that it is the person in question.” Because the electoral commission (EC), who run Trinity elections, have the same process for all its elections, in which a polling member takes your card to scan it which registers you as having voted, this possibility exists for every type of vote cast in Trinity.

However, checking the face of the cardholder, they claim, is often only a formality: “the EC don’t thoroughly check…we were never told to confirm someone’s identity, just request the student card.” When asked if it is possible for a student to use the cards of others to repeatedly vote, they responded: “with the speed at which we tried to accommodate voters on a busy day, it’s likely that someone could use the card of someone who looks vaguely similar to them.”

Furthermore, in class rep elections it is possible to use your card to vote in another class. Every student is capable of voting once, but “the Students’ Union have no way of telling what class the student is in when they go to vote.” If a student wanted to vote for their friends in another class rep election rather than in their own, there is nothing in place to prevent this, they claim.

Occasionally Wi-Fi can fail at polling stations, which means the EC’s system of registering people who have voted also fails. The standard way of dealing with this in all elections is to have students write down their names, student number, and voting preference on a piece paper or in a word document. Our source is critical of this method because it leaves open the possibility that someone could vote several times, as it allows votes to be submitted into the box without a card being scanned.

The final way is malpractice by the electoral commission. Since there are usually only two people at a polling station, “It’s entirely possible for someone working in a polling station to fill out stamp ballots and put them in the box or take stamp ballots away from the box if one of the other polling staff goes to the bathroom.”

However, our source further said: “while there are several potential ways to manipulate the elections big or small I’ve never have had any reason to expect anyone has. It is entirely theoretical.” Yet, considering that there are “definitive ways of exploiting the current paper ballot system,” it only makes sense to move to a more online system, they claim, as they see it as more secure.

When asked why Trinity has chosen to keep using the paper ballot system if the online system was, in their opinion, the better option, they said: “Part of it is tradition. What we have always had is perceived to work. There’s been less of an incentive to take the risks involved in adopting a new one.” As well as that, they claim: “there’s a perception that any type of computer based system wouldn’t be as easy to verify as paper ballot – they think it could manipulated or it would be impossible to prove that it hasn’t been manipulated.”

However: “there are several institutions that have secure online voting systems and it’s quite the standard for operations much larger than TCDSU and with easily as much at stake,” so, it is our source’s belief these criticisms are not grounded.

SU response

Speaking to Colm O’Halloran, Chair of the TCDSU Electoral Commission, many of the concerns raised by the source were revealed to be justified. While O’Halloran initially denied that an expired Trinity student card could be used to vote in a future election, he amended this in a subsequent email sent to Trinity News where he claimed his initial comment was inaccurate: “I checked again and was wrong on this. So long as they have a Trinity student card they can vote.”

However, O’Halloran also disagreed with our anonymous sources claim that the dates on the card are not checked: “If a student card does have a number from years ago then we will question whether the person is currently a registered student.”

O’Halloran also confirmed that there is in fact no way of verifying that a voting student is in the right class for a class representative election, saying “there’s no way to actually prevent, say, a Law student from voting in a Medicine election.” However, a student cannot vote for more than one class, he claimed, and therefore: “it doesn’t work to their benefit to vote in another class.”

Discussing the consequences of the scanning system failing, O’Halloran admitted: “That has happened in the past, where the Wi-Fi is generally not the best in Trinity,” and that in these cases the students’ ID numbers are recorded in a word document. When asked if there were risks related to this system, O’Halloran conceded that “possibly in that, you know, a student that has already voted could vote again. But it’s very unlikely.”

The risks associated with having only two individuals manning each polling station were also admitted. O’Halloran agreed that “obviously there’s the fact that someone could just grab a stamp ballot and stuff it in the box, but unlikely, very unlikely… not impossible though.”

However O’Halloran explained, with regards to the non-EC polling station workers, that he himself will “hand-pick them … I get in contact with people I know and I can trust,” and presented the fact that they are being paid as disincentives for malpractice.

O’Halloran was confident in the current polling system, believing that there’s “advantages and disadvantages” to both paper and online voting systems. Yet, he agreed that an online voting system would be preferable. “I think personally it would be a really good idea,” he said, and claimed several Trinity computer science students had already outlined a framework for building such a system themselves.

When asked about the cost of a system he said the “long-term investment would pay itself off in what we pay for paper ballot elections in two years.” O’Halloran added that the cost of such a system would range from €17,000 to €20,000, thereby involving long-term investment. He remarked that for the upcoming elections, TCDSU will have some form of online voting available for students on Erasmus or students who “can’t have access to polls.”

The benefit, O’Halloran claims, is it would likely lead to an increase in voter turnout, and help to identify correct voters for class rep elections.

Yet, O’Halloran mentioned that there is “a kind of a worry though.” For example: “online voting system could be taken down by a particular person, say if a candidate knew that someone’s campaigners were all going to vote at a particular time, and the voting system went down then, they couldn’t vote then, and that would kind of be a big flaw in the system.” He also mentioned the USI’s failed attempt at using online voting as a possible concern.

O’Halloran said the project has “hit a dead wall and at the moment I’m trying to talk to [computer science students], to see if they can get any further.”

Online voting

In 2012, the USI attempted to use an online system for a preferendum to help decide the union’s position in relation to student fees. According to a Trinity News piece at the time, the system “has been called into question after it emerged that database errors allowed former and part-time students to vote.”

One student also put up photos of him claiming to have accessed the administration account of the website used for collecting votes.

However, in other examples, online voting systems have been demonstrated to work effectively, including at DCU and Queen’s University, Belfast.

According to Stephen Keegan, a DCU student, the electronic system in place there is “a quick and simple process,” describing it as “brilliant” as it allows one“to vote from the comfort of home, and I bet that increases turnout.”

Trinity News spoke the Steve Conlon, a Computer Science lecturer responsible for managing the online voting system in DCU. The elections are held on a virtual learning environment called Loop, which is run by Moodle. Students log in and vote through a module called Students’ Union, which disappears once a vote has been cast. The system was built by a Moodle recognised programmer.

Conlon reports that as a result, voter turnout increased by 19% in the last election. Another benefit was that the system was accessible from anywhere in the world. Subsequently, the university received positive feedback from many Erasmus, nursing, and part-time students who had felt alienated from the elections beforehand.

Conlon further reports that DCU saved 150 hours of man-power between removing accounting and polling stations, as well as saving 190 kilograms of carbon, and 38,500 paper ballots.

Responding to some of the common fears and doubts related to online voting systems, and the perceived nature of their vulnerability to hacking, Conlon said that the likelihood of such a system being hacked is comparable to “someone going up to a ballot box and lighting it on fire with gasoline.”

He points out that the DCU system is backed up every 5 seconds, and again every 20 seconds by the Higher Education Authority. Every Irish university is run by the HEA net, Conlon says. Since the HEA is a state body, he suspects that anyone caught attempting to hack or tamper with the HEA net would face serious jail time and certainly would never be able to enrol in a university again.

Conlon also clarifies, responding to O’Halloran’s concern in the scenario of the system being brought down, that if their network were to go down their SU constitution has a “buffer mechanism” which allows them to extend the voting period.

Regarding the problems that occurred during USI’s preferendum, Conlon said that DCU’s voting system did not allow former students to vote. Students are organised in different cohorts, he explained, which separate students by enrollment status as well as faculties. He asserts that “only live registered students and pending registered students can access it. If you are a graduate you are taken out of the cohort.”

The USI vote failed because, according to Conlon, administrators said they “didn’t realise they were adding graduate students” and this is not a problem in DCU because of their cohort system.

While neither our anonymous source nor O’Halloran claim to know anyone who has taken advantage of these forms of manipulating the paper ballot in Trinity, the possibility of it happening is still there. These ways of tilting the election in a certain candidate’s favour are mostly things that could be done with a small amount of effort. It would not be hard for such a student to cover their tracks.

Bearing this in mind, both writers of this article felt it was important to expose these flaws before the upcoming election. Since candidates are expected to put a significant amount of effort into the weeks ahead, they deserve assurance that any rewards from these efforts are decided fairly.

Reporting by Conall Monaghan and Jessie Dolliver

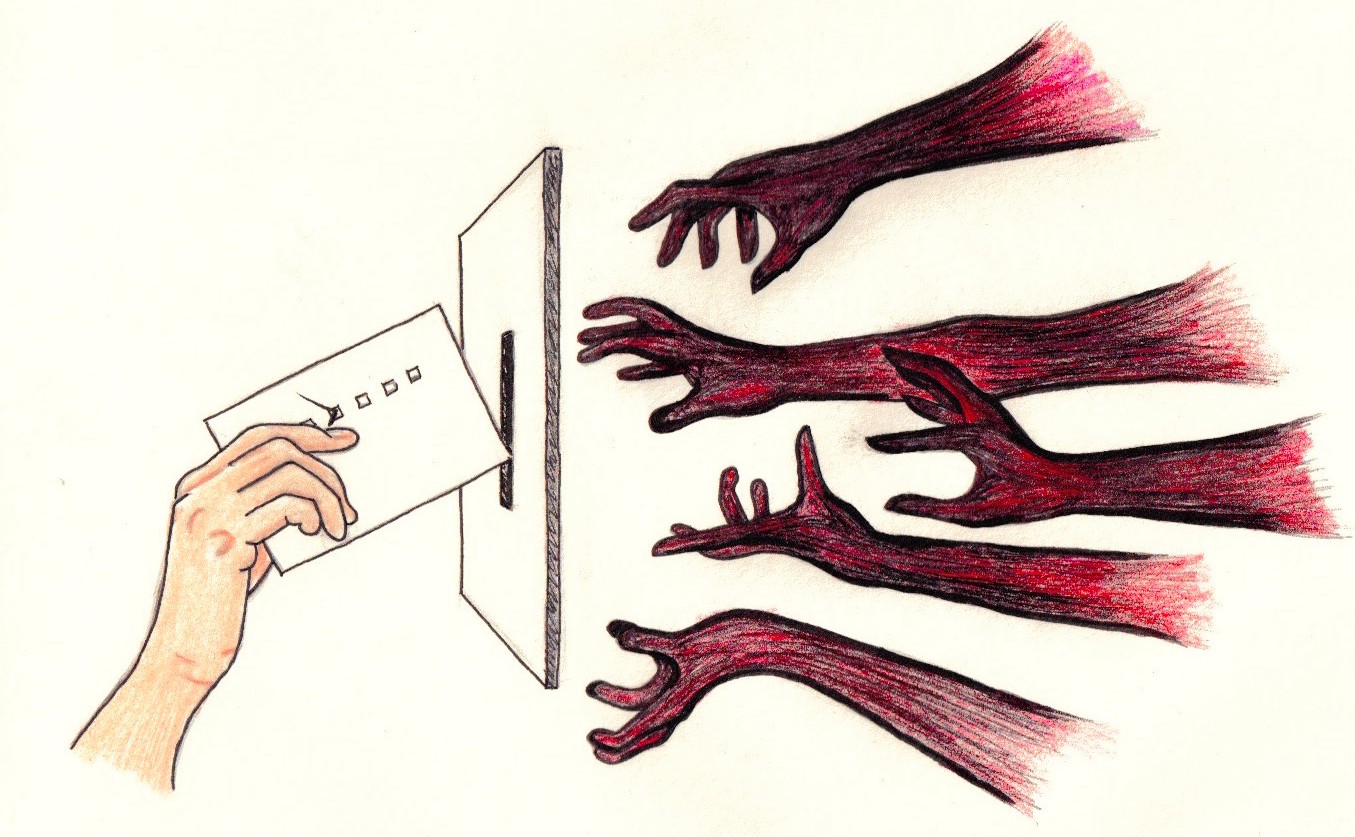

Illustration by Sarah Larragy